| title | author | affiliation | lang | bibliography | ccsLabelSep | csl | subfigGrid | subfigureRefIndexTemplate | abstract | keywords | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vernacular Patterns in Portugal and Brazil: Evolution and Adaptations |

Pedro P. Palazzo |

Visiting scholar, Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra; Associate professor, University of Brasilia School of Architecture and Urbanism

|

en-GB |

biblio.bib |

– |

_csl/chicago-author-date.csl |

true |

Traditional towns in Portugal and Brazil have evolved, since the

thirteenth century, a finely tuned coordination between, on the one

hand, modular dimensions for street widths and lot sizes, and on the

other, a typology of room shapes and distributions within houses.

Despite being well documented in urban history, this coordination was,

during the past century, often interpreted as contingent and as a

result of the limited material means of pre-industrial societies.

Nevertheless, the continued application and gradual adaptation of

these urban and architectural patterns throughout periods of

industrialization and economic development suggests they respond to

both long-lasting housing requirements and piecemeal urban growth.

This article surveys the persistence of urban and architectural

patterns up to the early twentieth century, showing their resilience in

addressing the requirements of modern housing and urbanisation.

|

|

In this article, I examine patterns of urban development in the traditions of the Portuguese speaking world. I aim to identify bodies of knowledge, practices, and regulations prevalent from the thirteenth to the mid twentieth century that offer examples of decentralised economic and regulatory controls over urban space, resulting in emergent order systems. These decentralised processes are not entirely at odds with the design of new towns, however. The interaction between vernacular development patterns and planned urban forms is a recurring feature in Portuguese and Brazilian towns and cities.

Beginning in the mid nineteenth century, these systems contend with fast and overarching changes in regulations and theories that put their resilience to the test. The rapid urban growth in the global South since the twentieth century has been addressed, predominantly, by means of theories and policies stressing centralised planning and economies of scale by both governments and the private sector. In Brazil, the enactment of a 'one size fits all' federal law on urban policy, nearly twenty years ago, is acknowledged to have resulted in the spread of boilerplate zoning codes across medium sized towns, as well as in massive public--private partnerships that have effectively outsourced urban planning to large corporations or even to banks. This has come at the expense both of democratic policy-making and of the agency of peripheral actors, such as small builders and communities excluded from formal land ownership.

In contrast, traditional Portuguese urbanism is predicated on few abstract regulations and, most important, a shared body of knowledge made up of both vernacular and 'classical' principles. Most planning decisions are, of necessity, entrusted to engineers and builders on the ground, acting on general guidelines set out by local or central authorities, especially in the broad expanses of colonial Brazil. Standard modules for such design decisions as the laying out of street widths or block and lot sizes are widely understood by builders. In spite of the high-profile urban renewal and expansion projects of the late nineteenth century, modelled after Haussmann's Paris or Anglo-Saxon garden cities, much of the urban fabric in Portugal and Brazil continues to be laid out in the same piecemeal fashion of Portuguese tradition, well into the twentieth century if not until the present.

Rather than considering the peripheral survival of traditional urbanism as an inconsequential holdout at the margins of progress, I propose to assert its legitimacy as a means to achieve resilient and sustainable cities within the socio-economic reality of peripheral building cultures. I do so by documenting its historical patterns, with an emphasis on vernacular and decentralised knowledge being leveraged by centralised planning determinations, as well as to the programmes of working class housing from the mid nineteenth century onwards. This general aim is achieved by establishing a typological series of traditional urban fabrics, evidencing the persistence and slow transformation of urban forms and building patterns.

The outline of this article takes its cues from Miguel de Unamuno's concept of 'intrahistory', translated into architectural scholarship in 1947 by Fernando Chueca Goitia, and akin to Fernand Braudel's concept of longue durée: not just a description of events taking place over long periods of time, but a methodological emphasis on the slow unfolding of social processes over the fast motion of discrete 'facts'. Because prevailing trends in art and architectural history have since belied Chueca Goitia's assertion that 'art history .... is purely intrahistory' [-@chuecagoitia:1981invariantes-castizos, 45], this study is a reminder that the continuity of traditions is one such long-term unfolding of historical processes, and thus a legitimate aspect of architectural history, theory, and practice.

The empirical methods of the British and Italian schools of urban morphology are promising for the reconstruction of genealogies of patterns and processes of typological development over long periods of time, beyond conventional periods defined by change of style in 'high art'. These methods can provide indirect hints to poorly documented features such as socio-economic arrangements, and in turn establish the continuity and resilience of urban patterns [@oliveira:2016urban]. The Italian 'school' of procedural typology provides a significant part of the theoretical groundwork regarding the possibility of establishing morphological genealogies of vernacular and traditional urban patterns [@cataldi:2015tipologie].

The analysis presented in this article thus assumes that making sense of typological continuity over several centuries is both possible and legitimate as an endeavour of architectural history. In the methodological framework of urban morphology and procedural typology outlined above, prevalent urban and architectural forms can be discerned by visual analysis of plans. The tabulation of abstract measurements as a source of statistical analysis not only is unnecessary in this method, but it also risks obscuring a concrete understanding of the urban space that stresses the clustering of patterns and the emergence of morphological districts [@raspiserra:1990concetto]. The persistence of spatial and topological relationships among elements---general lot shapes, block arrangements and configurations, and street and square hierarchies---is extracted from visual inquiry on the documentation [@conzen:2018core]. The goal of this analysis is not only to derive local morphological and syntactic patterns, but also to point out similarities and typologies prevalent among urban developments across time and space.

Documentation for this research has drawn on mainly graphical evidence of urban areas in Portugal and Brazil. These graphical sources have been collected from earlier research, municipal planning offices, and a few are extant historic drawings from original plans or later surveys that were preserved in archives. A number of new towns and urban extensions from the mid to late nineteenth century, laid out by engineers, surveyors, and builders, provide evidence of the continued use of traditional modules and of the adaptation of these modules to local conditions. Because there are few extant drawings from much of the nineteenth century, discerning these modules involves reconstructing original land subdivision patterns from present-day conditions. Even then, many towns in Brazil still lack reliable cadastral maps; this hampers the ability to conduct statistical analysis and error estimation from a set of precise measurements. At any rate, the assumption that there be, somewhere, historical towns preserved in a mythically pristine condition has led many architectural interpretations astray; even such iconic heritage sites as Ouro Preto, in Brazil's Minas Gerais state, underwent significant rebuilding and lot consolidation during the nineteenth century [@vieira:2016ouro].

This study evidences the significant continuity in urban and building modules used in Portuguese and Brazilian towns from the thirteenth to the twentieth centuries. Beginning with the 'birth' of modular urban design in Portugal in the thirteenth century, a limited set of lot and street dimensions dominates town planning. A first major inflection in these standards occurs in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, with an attempt to shape urban form in response to a systematic arrangement of the territory. Nevertheless, lot dimensions and house types undergo little change until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Then, the adoption of the metric system as well as the onset of positivist ideals of urban hygiene cause major changes in lot sizes and plan layouts. Even then, some aspects of traditional house types are carried on until the 1960s.

Portugal is part of the former Roman imperial province of Lusitania, later ruled by successive waves of Germanic and North African nobility. As such, she is representative to some degree of the broader trends in urban history of the western Mediterranean region. Roman agrarian colonies [@caniggia:1997analisi] have not made an imprint on the Portuguese landscape strong enough to condition later development; therefore, as in most of western Europe, the default Portuguese urban type is the linear village around a high street [@panerai:2012analyse].

In Fernandes's reconstruction of the ideal type, the village coalesces around a focal point or landmark, such as a chapel, a market, or the access to a castle [@fernandes:2014fundacao]. In the high street scheme (@Fig:casdevideA), the very deep lots around the main thoroughfare (rua da frente) and secondary axes (@Fig:casdevideB) have secondary frontages that establish a back street (rua de trás) on either side, as described by Teixeira [-@teixeira:2012forma]. A sequence of cross streets develops to link these parallel roads, forming large urban blocks (@Fig:casdevideC). These blocks are eventually broken up by alleys (travessas) linking the cross streets (@Fig:casdevideD), enabling the mature, dense build-up of the town core [@fernandes:2014fundacao]. Since most Portuguese urban areas originate in hill towns, the high street often takes the form of a spindle, with a binary network of main thoroughfares, further adding diversity to the urban fabric. This system forms hierarchical networks of streets and urban districts---each one a 'block of blocks', as it were, according to Orr1---that are able to support diverse uses and social classes within relatively small areas.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: {#fig:casdevide}

Reconstructed urban plan of Castelo de Vide, Portugal ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Alongside the 'organic' high street village type developing throughout Portuguese and Brazilian history, three major episodes of centrally mandated urban planning and design take place, more or less evenly spaced in time; all of them are spurred by the crown's drive to defend, populate, and manage Portugal's growing territory:

(1) Mid thirteenth century -- bastide-type new towns are conceived to secure Portugal's borders with Castille-and-León, as well as to promote food security for the young realm; (2) Early sixteenth century -- urban growth and overseas expansion promote new standards of parcel planning by both the crown and private developers; (3) Late eighteenth century -- the recognition of Portugal's independence and of her colonial possessions requires an efficient, and graphically 'rational', policy of new town planning.

The cumulative effect of these three episodes is not only to establish a Portuguese and Brazilian tradition of planned, yet adaptable, new towns [@lobo:2012urbanismo], but also that the modular dimensions of these new town lots become standard measurements in vernacular building practice. It is likely that this occurs because such measurements were widespread to begin with, and because of this were adopted in planned towns; the present state of archaeological knowledge does not, however, allow us to make assumptions about this possibility.

In the thirteenth century, Portuguese kings begin a policy of populating and fortifying their borders through the foundation of new towns---vilas novas or vilas reais---, akin to the French and English bastides in southern France and to the villas reales in Castille and León. Trindade has shown these Portuguese new towns operate on similar planning principles as their better known European kin [@trindade:2009urbanismo]. The Portuguese vila nova can be said to be a fortified high street village with a regular geometric plan and controlled allotment of land. Caminha on a promontory along the norther border, one of the earliest and best preserved examples, is organised around a straight high street, two back streets and two cross streets. The whole is encircled by a wall. As in many bastides, the parish church is sited away from the central crossing and placed near one of the gates, where it can be reached easily from the surrounding countryside. The market square and town hall are located at the opposite end of the high street (@Fig:caminha). Though there is a geometric principle behind the plan, its implementation is clearly dictated by expediency over a punctilious observance of orthogonality, and the edges of the town are required to bend to the military requirements of the fortifications adjusted to the terrain.

The vila nova layout establishes and observes certain geometric procedures to ensure regularity and the equal distribution of urban lots. These urban plans are executed in a modular scheme based on whole number ratios of the traditional Portuguese measurement unit: the hand, or palmo (abbreviated to 'p.'), equal to about 22.5 centimetres. 5 p. equal one Portuguese yard or vara, thus measuring 1.12 metre. The vara seems, in fact, to be the least multiple effectively used in most urban plans. At Caminha, according to the reconstruction proposed by Trindade (@Fig:caminha-modules), the basic elements of the urban design are 15 p.-wide streets (3.4 metres) and lots 25 p. (5.6 metres) wide by 60 to 75 p. (13.5 to 16.9 metres) deep [@trindade:2009urbanismo, 323-328].

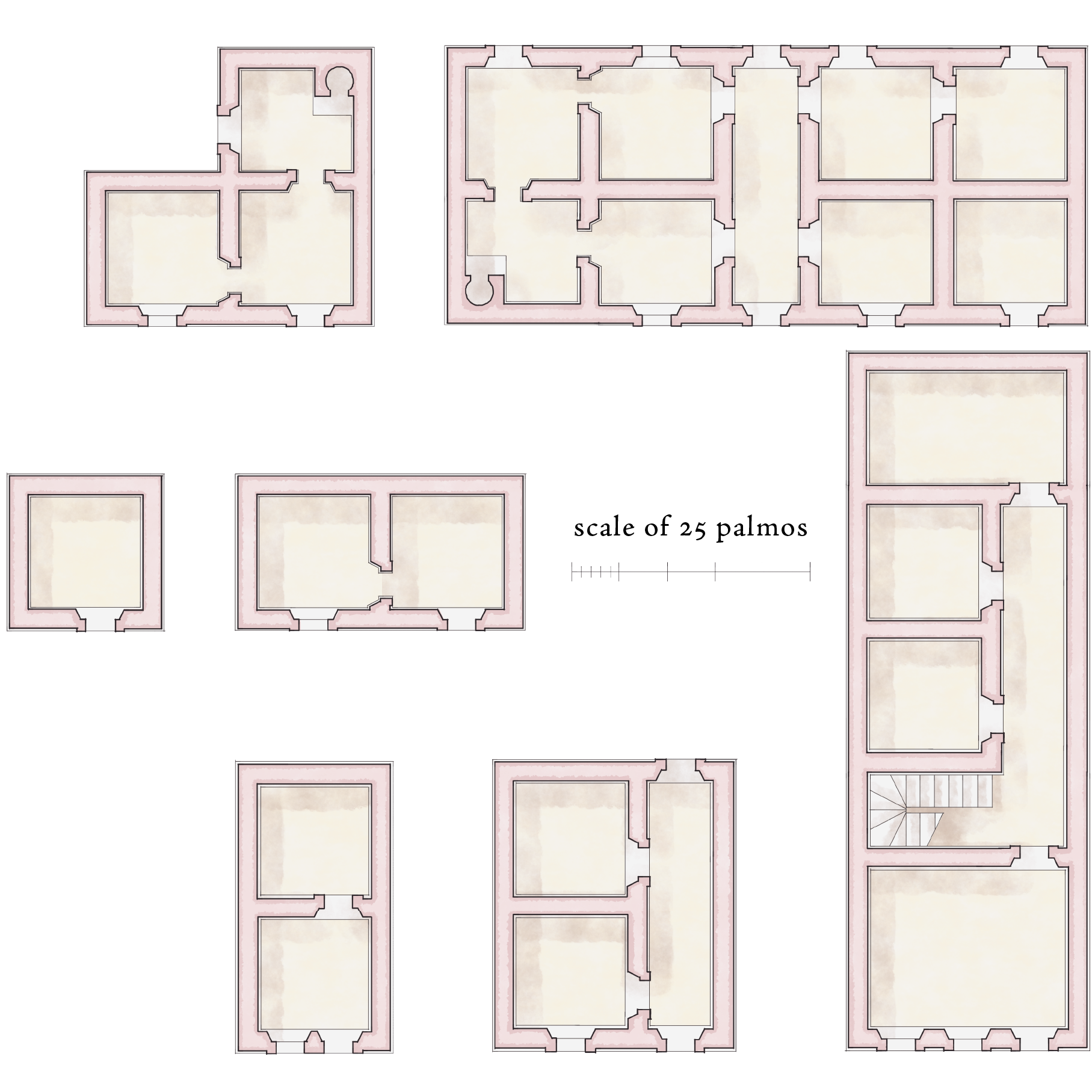

Other commonly used lot frontage dimensions are 20 p. (4.5 metres) and 30 p. (6.75 metres). This range of variations offers lot sizes convenient for a diversity of use cases, from tiny houses---often with no more than one or two square rooms---to aristocratic terraces or flats. As is the case in many Mediterranean building traditions, Portuguese urban house types are various arrangements of roughly square cells, up to 30 p. in length. The most common plan types for a 20 to 25 p. wide lot are either simple dwellings or shops with a longitudinal enfilade of up to three cells, or a differentiated arrangement of two large rooms at the front and back, with a string of small alcoves in between, accessed from a side hallway (@Fig:plans).

Relatively wide and shallow lots 30 p. wide by 60 p. deep are a particular standard of rural subdivision in Portugal, known as chão [@carita:1994bairro]. Because of this, they figure prominently in the suburban expansion of cities, such as in Lisbon's sixteenth century extramuros development known as the bairro Alto [@carita:1994bairro, 47-48]. Two 30 × 60 p. lots can be conveniently subdivided into three 20 p. lots for low-income housing or grouped to support a courtyard block of flats or an aristocratic house (@fig:chao); the latter case is attested in the bairro Alto during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, whereas the former occurs in nineteenth century suburban subdivisions in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The foundation of vilas reais sees a resurgence in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. A protracted animosity with Spain, for reasons of colonial dominance and dynastic legitimacy, sees king D. José I (reigned 1750--1777) and his first minister, the marquis of Pombal, keen on asserting the political and territorial integrity of Portugal. A string of new towns founded during this reign near every Spanish--Portuguese border---in both Europe and South America---signifies Portugal's ability to effectively control the territories claimed by her [@delson:1998novas], in addition to responding to new ideas about the 'rational' organisation of the territory, already being put in place by Spain [@oliveras:1998nuevas].

Portuguese new towns such as Vila Real de Santo António ([@Fig:vilareal]), on the mouth of the Guadiana river in the Iberian peninsula, exhibit both the persistence of traditional land subdivision patterns and the changes brought about in the concept of 'rational' planning. Vila Real de Santo António, founded in 1773, is laid out around a single central square on which both the town hall and the parish church are located; the market has its own, dedicated building away from the main square, now devolved exclusively to civic and symbolic representation. Here, unlike at Caminha, the engineers make it a point to adhere strictly to the gridiron plan: it helps that the town is intended as a residential garrison and fishing harbour, while the actual fortifications are sited on higher ground.

To facilitate the movement of troops and goods, but also to highlight the clarity and monumentality of the plan, the streets are much broader than in the thirteenth century new towns: at 40 p. across, they are more than double the breadth of the Caminha streets and rather oversized for the single story houses in the original plan. Also, due to the layout focusing on the central square, a generous 350 p. across, the street hierarchy of older planned towns is lost in Vila Real de Santo António. Despite all these transformations in the eighteenth century attitudes towards urban design, lot sizes display remarkably little change. The same 25 p. frontages are used in thirteenth century Caminha and in eighteenth century Vila Real de Santo António, with only a slight reduction in depth, from 60 to 50 p. The exact same dimensions for the central square and lot frontages are used in the 1773 town plan for São Luiz do Paraitinga, a highway stop on the road to the Brazilian gold mines [@derntl:2013metodo]. Street sections are, however, somewhat less consistent, ranging from 40 p. at Vila Real de Santo António to 60 p. at São Luiz do Paraitinga---a generous breadth first attempted in the post earthquake rebuilding of Lisbon---and up to 100 p. elsewhere in colonial Brazil [@derntl:2013metodo].

These eighteenth century efforts at rationalising the territory by means of carefully placed and planned new towns are also remarkable in that they seem to be the first designs, in Portugal, to mandate specific building types or the placement of houses. Such matters appear to have been understood as self-evident or less relevant in earlier periods. The project for the rebuilding of Lisbon sets the trend here, associating the regularity of the new city blocks and lots with the uniformity of mandated façades [@franca:1989reconstrucao]. Similarly, a number of surviving drawings for new outposts in the Brazilian frontiers, such as that of Taquari, in the south ([@Fig:taquari]), establish simple façade designs that let one guess the single room layout behind them.

Centralised territorial planning in Portugal and Brazil comes to a sudden halt at the death of D. José I in 1777, not to resume for almost a century thereafter. Nevertheless, singular designs for new towns or extensions during this lull do carry on the principles and modules of Portuguese tradition. Royal and imperial new towns in Brazil, such as Niterói (1819) and Petrópolis (1843), evidence the continued use of eighteenth century military engineering principles, with strictly geometric layouts. As late as the 1850s, two new provincial capitals in Brazil, Teresina and Aracaju ([@Fig:aracaju]), are planned using the eighteenth century module of 60 p. wide streets forming a gridiron around a main square facing the river.

The mid nineteenth century urban growth of Rio de Janeiro also shows evidence of the persistence of traditional modules. A large fringe belt of public land, the rossio, west of the city centre is developed during the first half of the nineteenth century according to these modules: its streets are 25, 30, and 100 p. in breadth, and blocks are subdivided, whenever pre-existing conditions allow, into 20 p. lots ([@Fig:gotto]). This area grows into one of the densest and socio-economically diverse neighborhoods outside the city centre, and also one of the best preserved nineteenth century districts. This is, in part, due precisely to the extremely fragmented land ownership pattern of its narrow lots, which has prevented the consolidation required for large-scale redevelopment.

Farther to the west, mid nineteenth century development on green fields introduces notable, though short lived, variations in the form of 15 and 18 p. (3.4 and 4 metre) lots destined for working-class rental. These extremely narrow lots sometimes unfold to extreme depths, creating cortiços (slums or tenements) akin to the contemporary ilhas in Oporto. In Rio, these narrow lots are rapidly overrun by demand for bulkier apartment or commercial buildings, however. This short life span of the extremely narrow lots contrasts with the resilience of the 20 and 25 p. lots on the former rossio.

Haussmanian percées by the federal government during the first half of the twentieth century end up opening several stretches of this area for the construction of large office buildings, which compare poorly to the historic fabric in terms of diversity and pedestrian life. Nevertheless, those percées that take place during the first decade of the twentieth century demonstrate how resilient the Luso-Brazilian building traditions are. De Paoli has noted one of the goals of these early urban renewal interventions is to force the consolidation of narrow lots into broader ones, at least 6 to 7 metres wide (a measurement reminiscent of the suburban Portuguese 30 p. lot?). However, several such consolidated lots are redeveloped with two or more independent structures side by side, rather than one large building [@paoli:2013outra, 36]. New mixed use buildings granted planning consent between 1903 and 1908 often preserve the side hallway plan type ([@Fig:saopedro]; compare with [@fig:plans]).

Meanwhile, in 1834, Portugal officially adopts the metric system, followed much later by Brazil in 1872. Metrification directly impacts the construction trades and urban subdivision, not the least because it is accompanied by a surge in new municipal and national regulations on building and urban development. An evidence of these changes is recorded in the urban fabric of the Portuguese city of Oporto, which grows significantly over the course of the nineteenth century due to industrial development. The earlier growth spurs, along pre-existing roads, exhibit traditional urban lot frontages 20 or 25 p. wide. On the rua do Almada, a new thoroughfare opened in 1761 but only developed much later, on the other hand, lots are standardised at 5 metres wide ([@Fig:almada]).

Metrification and the ensuing drive for ever more comprehensive building regulations are also at play in early twentieth century São Paulo, Brazil's own industrial powerhouse. Lemos observes that a positivistic will to 'improve' low-income housing in that city [@lemos:1999republica]. Turn of the century regulations deal chiefly with natural lighting and ventilation requirements in some (not all, at first) rooms of the house. This results, at first, in conservative (and inconvenient) designs where the side hallway becomes an open court; only later do actual side setbacks become common, requiring wider lots ([@Fig:bentofreitas]).

Even as the example of São Paulo contributes to the dissemination of side yard houses throughout Brazil in the early twentieth century, Portuguese builders take a different approach to the mandate of natural lighting and ventilation. Several public and private developments of the early twentieth century, especially in the centre and south of Portugal, experiment with an 8.5 to 9 metre wide suburban housing type made up of four cells arranged in a square, with or without a hallway. A number of variations on this type are to be found at Entroncamento, a railway junction company town from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries [@paixao:2016bairros]. These dwellings, designed by architects and engineers, are arranged in pairs, evidencing some familiarity with current concepts of garden suburbs ([@Fig:entroncamento]). Their architectural style has often been condemned as merely nostalgic, representing a superficial attachment to familiar visual cues and, worse, playing into conservative politics [@rosmaninho:2002casa]. Contrary to this interpretation, which itself betrays a superficial study of such houses, however, these planned dwellings demonstrate an understanding of the long typological history of Portuguese houses, and a conscious effort to adapt it to modern urban principles.

The increasing popularity of garden city principles as well as a tendency to round up metric dimensions to 10 metre frontages cause the ultimate break down of this process. In the 1960s, the widespread use of 10-metre frontages encroaches even on historic towns such as Ouro Preto ([@Fig:op-santacasa]). Nevertheless, the damaging effect of this transformation on the character of traditional urban areas is not noticed by historic preservationists until much later, in the 1980s [@motta:1987sphan22, 114]. By then, the exponential urban growth of the post-war era had already caused major loss of character in such sites.

This article surveyed the emergence and transformation of traditional urban and building patterns in Portugal and Brazil, singling out recurring measurements and modules. These town building traditions remain sensibly stable for nearly five centuries, from the early thirteenth to the mid eighteenth century. Even as the territorial policies of 'enlightened despotism' in Portugal impose new, centralised and monumental urban forms onto the landscape, these forms accommodate most of the existing practices regarding lot dimensions and house types. A crisis in traditional patterns arises more sharply with the adoption of the metric system in Portugal and Brazil during the nineteenth century, followed by the turn of the century positivist approach to comprehensive urban and building regulation. Still, elements of traditional building types persist well into the twentieth century, only to break down in the second half of that century.

This kind of study relies mostly on planned new towns and large urban expansions, which show the interaction between top-down designs and bottom-up vernacular practice. Its most significant drawback is, therefore, its reliance on a centralised 'act of will' for evidence of the modularity of decentralised patterns. Urban infill and redevelopment can provide insights on the persistence of generic building types, but the constraints of the existing fabric and land ownership patterns are likely to supplant any explicit choice of dimensional modules. On the other hand, these same constraints foster the continued use of plan layouts adapted to the existing lot sizes. A larger and more detailed body of architectural documentation might shed light on the relationship between these constraints and the dimensional limits the traditional building types can reach.

Customary measurement units play a significant part in the stabilisation of urban and building types. The palmo (hand) and especially its five-fold multiple, the vara (yard) provide sensible, minimal modules for sizing construction elements and laying out urban units---most importantly, lot and street widths. Lots 20, 25, and 30 p. wide occur consistently up to the mid nineteenth century, both in developments planned and controlled by the state, and in the private dynamics of suburban extensions to major cities. These dimensions support specific building types, consisting of linear arrangements of spatial cells with or without hallways, that change very little up to the late nineteenth century.

The successive shocks of metrification and of positivist building regulations, in the mid to late nineteenth century, provoke conspicuous changes in urban and building morphology, as well as the eventual split of the Portuguese-Brazilian tradition into two separate national trends. Even historic preservation has done little to stem the decline of traditions, not the least due to the prevailing emphasis, in preservation theory and practice throughout the twentieth century, on upholding the fatalist distinction between 'original' and 'addition' rather than on protecting the continuous process giving rise to traditional urban areas. Despite this loss, traditional plan layouts continue to provide cultural references and models for new projects well into the first half of the twentieth century. The spatial efficiency and functional flexibility of such types as the townhouse, endowed since the late 1800s with a side yard, and the foursquare cell house, compare favourably to recent types of housing and urban development.

The long-term stability of Portuguese building modules is a case that vindicates, in our age so fond of 'microhistory', the importance ascribed to intrahistory by Chueca Goitia and Braudel. Yet its value also reaches beyond the domain of the historian's craft: it is a statement on the importance of continuity to design practice. The study of modules in urban and building development shows the resilience of morphological patterns and professional practices through time. Standardised street widths, lot sizes, and building types are valuable evidence of cumulative problem solving; aimless experimentation and constant starting over from scratch, by contrast, have resulted in so many failed architectural and urban projects.

Footnotes

-

@orr:2018five. I am grateful to Douglas Duany for introducing me to Orr's concept of a 'block of blocks.' ↩

![Reconstructed foundation town plan of Caminha, thirteenth century, author's drawing after [@trindade:2009urbanismo, 157]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/66/Caminha_plan_13c_reconstructed_01.png)

![Reconstructed modular platting of Caminha, thirteenth century, author's drawing after [@trindade:2009urbanismo, 328]. Units: 1 palmo = 22.5 centimetres and 1 vara = 5 palmos = 1.125 metre](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/88/Caminha_plan_13c_ideal.png)

![Approved building application on rua de São Pedro, Rio de Janeiro, c. 1903. Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, reproduced by de Paoli [-@paoli:2013outra]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/05/Building_on_rua_de_S_Pedro_Rio_de_Janeiro_1903.jpg)