Remote repositories are versions of your project that are hosted somewhere (GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket, Gitea, and many more...).

Throughout this tutorial we'll work with, you guess right: GitHub!

In the previous tutorial you've already cloned the repo we are practicing on. If you haven't, you can do it by:

git clone https://github.com/exit-zero-academy/NetflixMovieCatalogWhen cloning a repo, Git keeps a reference to the original repository under the name origin:

$ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/exit-zero-academy/NetflixMovieCatalog (fetch)

origin https://github.com/exit-zero-academy/NetflixMovieCatalog (push)Later on, you can push commits of some branch to the origin remote (only if you are authorized to do so), for example:

git push origin mainForking creates a personal copy of someone else's repository on your GitHub account.

Unlike cloning, which keeps a reference to the original repository under the name origin, forking creates a distinct copy under your GitHub username.

Fork the NetflixMovieCatalog repository by clicking the Fork button on the repository's GitHub page.

After forking, you can clone your forked repository:

git clone https://github.com/yourusername/NetflixMovieCatalogFrom now on, unless specified otherwise, you should work on your forked repo.

Let's make some changes on branch main for your forked repo, commit and push them to remote by:

git push origin mainHaving issues to push? You have to authenticate against your remote server first. You can do it either by SSH or HTTPS (username and access token), depending on the protocol used when you cloned the repo.

Perform the git remote -v command and check the URL to determine which authentication method you should use.

You use HTTPS if you see something like:

$ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/yourusername/NetflixMovieCatalog (fetch)

origin https://github.com/yourusername/NetflixMovieCatalog (push)Otherwise, if you see something like the below example, you use SSH:

$ git remote -v

origin git@github.com:yourusername/NetflixMovieCatalog.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:yourusername/NetflixMovieCatalog.git (push)- Create a Personal Access Token.

- Push your changes by:

git push origin main.

By default, push command will prompt you for your username and token.

You can keep credentials stored in memory so further push command would not require authentication:

git config --global credential.helper cacheThat way, your credentials are never stored on disk, and they are purged from the cache after 15 minutes.

If you want to save the credentials on disk (as a plain-text file):

git config --global credential.helper storeThat way credentials are never expire.

Note

The above configurations are stored under ~/.gitconfig file. This file includes user preferences, credential helpers and more.

Generate new SSH keys by:

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your_email@example.com"Add the public key to your GitHub account.

When you clone the repository, git fetches all the history exists in the repo, including all branches.

You can list all remote branches by:

$ git branch -a

* main

remotes/origin/HEAD -> origin/main

remotes/origin/mainIn the above output, you can see your local branches (e.g. main) as well as its corresponding Remote-Tracking branch: remotes/origin/main (or shortly origin/main).

Remote-tracking branches are a local copy of branched as they exist on remote (on GitHub in our case) .

They take the form <remote-name>/<branch>.

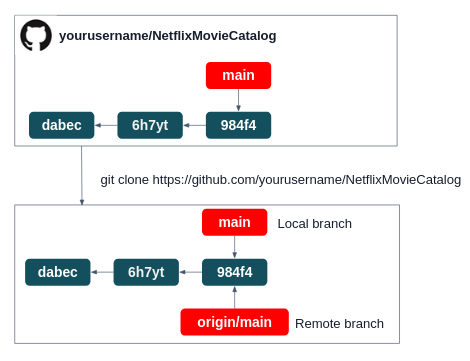

Let's visualize it.

Saying you've just cloned a fresh copy of our repo:

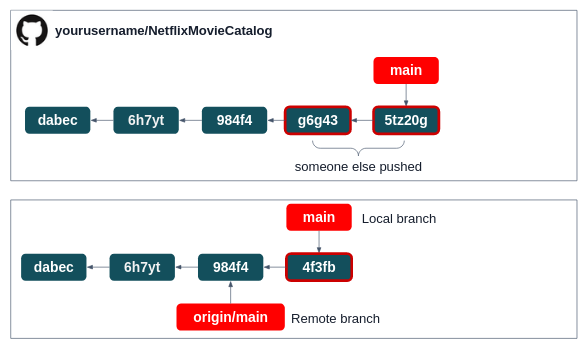

If you do some work on your local main branch, and, in the meantime, someone else pushes to GitHub, then your histories move forward differently.

Also, as long as you stay out of contact with your origin server, your origin/main pointer doesn't move:

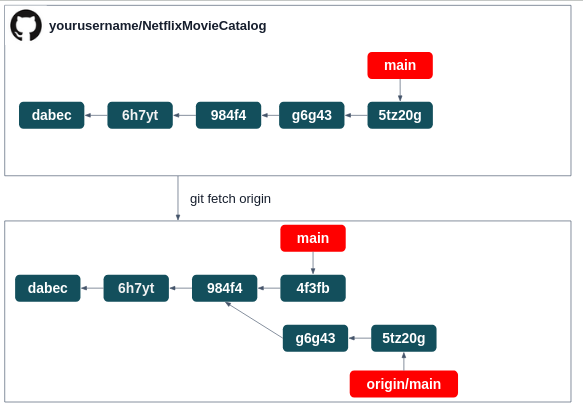

To synchronize your work with a given remote, you run the git fetch origin command.

This command fetches any data from origin that you don't yet have, and updates your local remote-tracking branches, moving your origin/main pointer to its new, more up-to-date position.

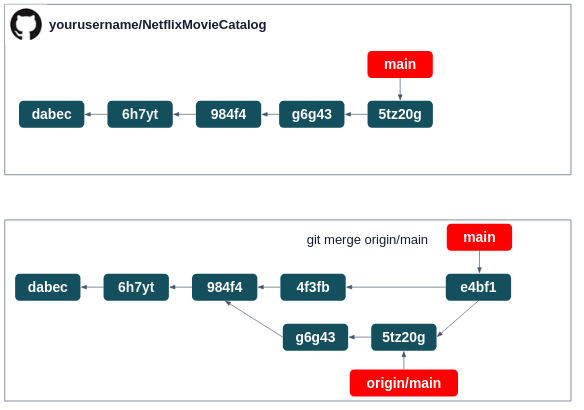

Then, if you want to merge the commits of origin/main (which reflects the main branch as it seen in GitHub), you run the git merge origin/main command:

Tip: Instead of running the git fetch and immediately after the git merge command, you can run git pull which is essentially does the same.

It's important to note that when you do a clone/fetch that brings down new remote-tracking branches, you don't automatically have local, editable copies of them.

Let's say you want to work on some of the branches which exists on GitHub, for example origin/test.

In this case, you don't have yet a local branch test to work on - you have only the origin/test branch which can't be modified.

In order to work on that branch, you need to check it out as a new local branch, while you base it on your remote-tracking branch:

$ git checkout -b test origin/testme

Branch test set up to track remote branch test from origin.

Switched to a new branch 'test'Git automatically creates test as what is called a tracking branch (and the branch it tracks, origin/test, is called an upstream branch).

Tracking branches are local branches that have a direct relationship to a remote branch.

If you're on a tracking branch and push it, Git automatically knows which remote branch to push to.

Let's say the original NetflixMovieCatalog repo, the one you've forked from has some new commits that you don't have in your fork. This is a very common scenario when developers are working on new features on a project that forked in the past.

Now you want to be up-to-date with the original project (the upstream repo), to receive the new features and bugfixes.

You can achieve that by adding another remote to your fork, as follows:

$ git remote add upstream https://github.com/exit-zero-academy/NetflixMovieCatalog

$ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/yourusername/NetflixMovieCatalog (fetch)

origin https://github.com/yourusername/NetflixMovieCatalog (push)

upsream https://github.com/exit-zero-academy/NetflixMovieCatalog (fetch)

upsream https://github.com/exit-zero-academy/NetflixMovieCatalog (push)Now your local clone has 2 remotes: origin, which represents your fork, and upstream, which represents the original repo.

Note: upstream is a very common remote name to the original repository.

Now you can use upstream in the pull/fetch commands to receive updates:

$ git fetch upstream

remote: Counting objects: 43, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (36/36), done.

remote: Total 43 (delta 10), reused 31 (delta 5)

Unpacking objects: 100% (43/43), done.

From https://github.com/exit-zero-academy/NetflixMovieCatalogIf you want to update your main branch according to upstream's main:

git checkout main

git merge upstream/mainWork with your friend. Use either Pycharm UI or CLI.

- Add your friend as a collaborator to your fork repo.

- Ask him/her to clone a fresh copy.

- Ask to commit and push some changes to the

mainbranch. In the meantime, you also commit some new changes but don't push them, let your friend pushing first. - After your friend has pushed, try to push yourself. What happened? Why? How can you proceed?

- You and your friend should now commit some changes which introduce conflicts (edit both of you the same file same line, e.g. change the port number in

app.pyto different numbers). - Ask your friend to commit and push first, you only commit, don't push.

- Now pull, resolve the conflict (it's recommended to use Pycharm's UI).