-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 0

/

Copy pathhandout.Rmd

1022 lines (814 loc) · 37.6 KB

/

handout.Rmd

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

684

685

686

687

688

689

690

691

692

693

694

695

696

697

698

699

700

701

702

703

704

705

706

707

708

709

710

711

712

713

714

715

716

717

718

719

720

721

722

723

724

725

726

727

728

729

730

731

732

733

734

735

736

737

738

739

740

741

742

743

744

745

746

747

748

749

750

751

752

753

754

755

756

757

758

759

760

761

762

763

764

765

766

767

768

769

770

771

772

773

774

775

776

777

778

779

780

781

782

783

784

785

786

787

788

789

790

791

792

793

794

795

796

797

798

799

800

801

802

803

804

805

806

807

808

809

810

811

812

813

814

815

816

817

818

819

820

821

822

823

824

825

826

827

828

829

830

831

832

833

834

835

836

837

838

839

840

841

842

843

844

845

846

847

848

849

850

851

852

853

854

855

856

857

858

859

860

861

862

863

864

865

866

867

868

869

870

871

872

873

874

875

876

877

878

879

880

881

882

883

884

885

886

887

888

889

890

891

892

893

894

895

896

897

898

899

900

901

902

903

904

905

906

907

908

909

910

911

912

913

914

915

916

917

918

919

920

921

922

923

924

925

926

927

928

929

930

931

932

933

934

935

936

937

938

939

940

941

942

943

944

945

946

947

948

949

950

951

952

953

954

955

956

957

958

959

960

961

962

963

964

965

966

967

968

969

970

971

972

973

974

975

976

977

978

979

980

981

982

983

984

985

986

987

988

989

990

991

992

993

994

995

996

997

998

999

1000

---

title: "Introduction to R"

author: "Jacob Simmering"

date: "Nov 1st, 2017"

output:

html_document: default

---

```{r setup, include=FALSE}

knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE)

library(tidyverse)

```

# Setup

You will need to have a version of R installed. It can be downloaded for your

system at [CRAN](https://cran.r-project.org/). Also you will want to install

the `tidyverse` inside R. You can do this by running

`install.packages("tidyverse")` in an R session.

Finally, while not required, the [RStudio IDE](https://www.rstudio.com/) will

make your R sessions much

easier to manage.

# Overview

## The R Langague

I am not going to spend a lot of time R as a language. I'll cover some syntax

as we reach it. I'll cover just a few brief terms and conventions here.

*Packages* are contributed extensions to the R language to enable specific

tasks or analyses. If you are familiar with Python, these are like libraries or

gems in Ruby. Most of the time, there is a contributed version on CRAN that you

can easily install with `install.packages("<package name>")` in your R session.

It will download and install the requested package as well as any dependencies

required. Once a package is installed, you can load it into your session with

`library(<package name>)`. Quotes are required to install but optional when

loading the library.

The `<-` (read as "gets") is the primary assignment operator in R. If you want

to set the value of `x` to `1`, you would run `x <- 1`. This is directional,

so `1 -> x` is also valid (useful if you just typed a long line and forgot

to assign it, but probably not good practice!). You can use `=` for assignment

(and indeed need to when you are passing function arguments) but for whatever

reason that is not standard practice.

The operator `%>%` is added when you load the `tidyverse` package and is known

as the "pipe" operator. You can understand read this as "then". This is used

to string together a series of operations into one group while splitting across

lines for readability and avoiding nesting of parenthesis. We'll discuss this

later in context.

There are three atomic data types in R.

* "numeric" - this stores floating point and integer values. Typically, it will

store the value as a double precision floating point but integer can be

forced if desired.

* "factor" - this looks like a string but it isn't! Factors are categorical

variables with discrete levels (e.g., male vs female, dog vs cat vs mouse).

In R, they are actually stored internally as a series of integers and R converts

these integers to labels (e.g., 1 = male, 2 = female) when it shows output.

This can be confusing because they look like strings but aren't - it makes sense

in R's standard statistical use-case but will almost certainly make everyone

groan at least once.

* "character" - this is actually the string-type in R. Most of the tools I'll

discuss today don't convert characters to factors but historically R has

coerced characters into factors when reading data into a session.

There are a set of higher level data types in R:

* "vector" - a vector is 1-D collection of values, all of the same data type.

A "vector" in R and a "vector" in math mean approximately the same thing.

For instance `c(1, 2, 3)` is a vector as is `c("A", "B", "C")` (`c()` is the

function used to construct a vector, `c` standards for "combine" or

"concatenation"). R will automatically convert a vector with mixed types into

the most strict atomic data type that can hold all of the values in the vector.

For instance, `c(1, 2, "A")` will become a string of character values.

* "matrix" - a matrix is a 2-D collection of values. This is the same as a

"matrix" in math. Like a vector, it can only hold one atomic data type.

* "array" - an array is a generalization of a matrix to any number of

dimensions. This can be useful to hold data where you have clear "slices"

(e.g., intensity by x and y at several difference values of t). Again, this can

only hold one atomic data type.

* "data.frame" - a data.frame is the primary data storage object in base R. It

is a collection of vectors, each displayed as a column, and is analogous to

a table or spreadsheet. The columns can be of different types.

* "tibble" - a tibble (a corruption of the word "table" which was abbreviated as

"tbl" in the output) is an extension of the data.frame provided by the `tibble`

package in the `tidyverse`. The main advantages of a tibble are a better print

method and it makes it a little harder to get yourself in trouble. For more

on tibbles see [R for Data Science Chapter 10](http://r4ds.had.co.nz/tibbles.html).

* "list" - a list is a collection of any R data types with each element being

potentially a different type. These come in handy when doing functional

programming tasks.

I am going to be mostly using tibble type objects here. We will touch briefly

on lists towards the end if time permits. I'll mention vectors in a few places

as they will be used next week.

## The Packages We'll Use Today

I am going to cover using R, mostly focusing on data importation, manipulation

and visualization. I'll also cover the different data types in R, extensions of

these data types and, time permitting, some functional programming in R. Next

week Aaron Miller will cover machine learning in R.

Most of the examples in this book will use a package called `tidyverse`. The

tidyverse is a collection of tools to help with the data importation and

manipulation challenges in R. Specifically, we will discuss the following

packages this week

* `dplyr`

* `ggplot2`

* `tidyr`

* `readr`

* `stringr`

* `purrr`

* `broom`

## The Data We'll Use Today

We will be using the data sets in the `nycflights13` package. However, instead

of using the package we are going to read in the data directly. We'll discuss

reading in the data next, but first a brief overview of the data. The data is

a summary of the on-time data for all flights that left NYC in 2013 and

includes "metadata" such as airline, airport the plane was flying to, weather

and the plane. The data was collected and compiled into the R package by

Hadley Wickham in 2017.

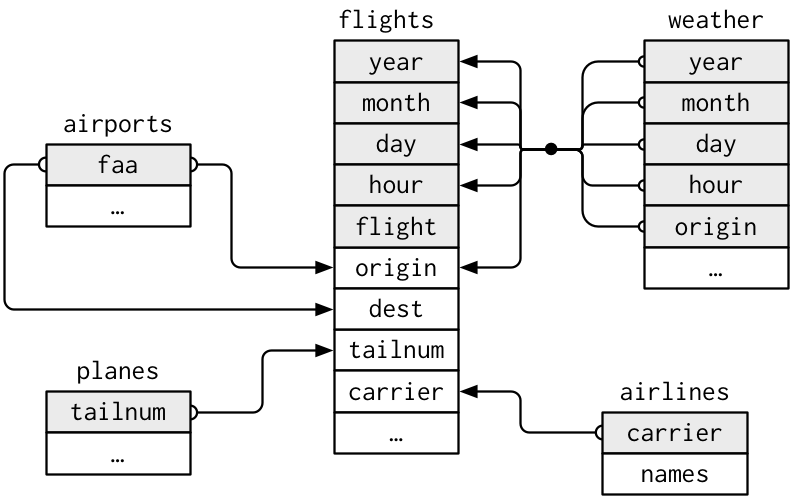

There are five tables. They are

* airlines

* airports

* flights

* planes

* weather

A sample schema showing how they are joined (taken from R4DS)

# Data Science Workflow

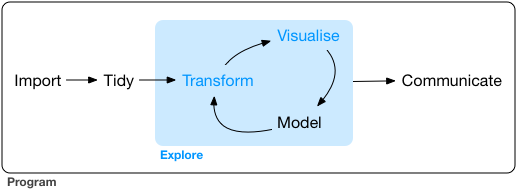

The tidyverse suggests a workflow of data exploration and analysis depicted

in the figure below (taken from R for Data Science)

The ideal is that you import your (potentially unstructured/messy) data,

tidy it (convert it into a cleaned, rectangular format, more on tidy data later)

and then enter the analysis/exploration cycle. Here you start by transforming

your data, visualizing relationships, modeling those relationships and then

potentially returning to the transformation and repeating the process.

Once you have finalized the model/completed the analysis, you communicate

your results.

The tidyverse package has a number of child packages that cover these tasks

more-or-less in a 1:1 fashion:

* `readr` covers many forms of data import into R

* `tidyr` assists with tidying messy data and getting it into the desired

format

* `dplyr` covers many, if not most, transformations of the data you might want

to do

* `ggplot2` is a powerful and visually appealing tool for producing

visualizations of your data and any relationships within

* `modelr`, `purrr` and the base R functions `lm()` and `glm()` form the bulk of

the modeling stage

* `knitr` provides an easy way to embedded R code and results inside Markdown

files for easy drafting of reports and communication

I will briefly cover the use of `readr` and `tidyr` today. I will cover

`dplyr` in-depth and provide an introduction to `ggplot2`. There won't be time

to cover the regression and model methods in much detail without getting bogged

down in the stats

# Data Import

For more information see

[Chapter 11 of R for Data Science](http://r4ds.had.co.nz/data-import.html)

Start a new R script in RStudio and add the following to the top of the script

```{r eval=FALSE}

library(tidyverse)

```

And run the line (click on the "Run" icon or put your cursor on the line and

press crtl-enter (Windows, Linux) or cmd-enter (OS X)). This should send your

code to the console to execute.

If you see the message

`Error in library(tidyverse) : there is no package called 'tidyverse'` it means

that the `tidyverse` package is not installed. In the console, run

`install.packages("tidyverse")` to install it and then re-run the line.

If you see the following:

```

Loading tidyverse: ggplot2

Loading tidyverse: tibble

Loading tidyverse: tidyr

Loading tidyverse: readr

Loading tidyverse: purrr

Loading tidyverse: dplyr

Conflicts with tidy packages ---------------------------------------------------

filter(): dplyr, stats

lag(): dplyr, stats

```

It means that you have successfully loaded the `tidyverse` and related packages

into your R session. The `Conflicts with tidy packages` section lists places

where there are two functions with the same name being loaded into the global

namespace. By default, the last function loaded will be the default. For

instance, if I run the function `lag()` it will use the `lag()` as defined by

the `dplyr` package since I loaded that after the `stats` package was loaded.

If I want to access the `stats` version of `lag()`, I can explicitly identify

the namespace using the format `namespace::function()` or `stats::lag()` in

this case.

We are going to use the `readr` package to load our data. There are specialized

functions in the `readr` package to read tab-separated files, fixed-with files,

delimited files and comma-separated files. We are going to focus on csv's, but

you can read in pretty much any plain-text file with `readr`.

The main function we want to use is `read_csv()`. If you enter `?read_csv` in

the console, you should be able to see the Help package for the `read_csv()`

function. You'll see the description that: "read_csv() and read_tsv() are

special cases of the general read_delim(). They're useful for reading the most

common types of flat file data, comma separated values and tab separated values,

respectively. read_csv2() uses ; for separators, instead of ,. This is common in

European countries which use , as the decimal separator." Looking under the

Usage entry, we see

```

read_csv(file, col_names = TRUE, col_types = NULL,

locale = default_locale(), na = c("", "NA"), quoted_na = TRUE,

quote = "\"", comment = "", trim_ws = TRUE, skip = 0, n_max = Inf,

guess_max = min(1000, n_max), progress = show_progress())

```

That is a lot of arguments to manage and the arguments section goes through

them in detail. We won't need to change many of these from defaults. In general,

you only need to worry about setting `file` and, occasionally, `col_types`.

I've provided all of the data we are going to use in the `data` directory of

this repo. Let's one of the files and print it:

```{r data_load_1}

airlines <- read_csv("data/airlines.csv")

airlines

```

The section that reads

```

## Parsed with column specification:

## cols(

## carrier = col_character(),

## name = col_character()

## )

```

tells us about the data, specifically, the variables the parser found and their

types. In this case, there are two variables, carrier and name, both of which

are characters.

When we print out the object, we see that it is a tibble with 2 columns and

16 rows. `carrier` appears to be a short 2-letter abbreviation for an airline

and `name` is the full name of the airline company.

We can do this with the rest of the files as well:

```{r data_load_2}

airports <- read_csv("data/airports.csv")

planes <- read_csv("data/planes.csv")

flights <- read_csv("data/flights.csv")

weather <- read_csv("data/weather.csv")

```

We again see a list of all the variables in the data set and their types. You'll

notice that even more complicated types, such as datetime, were recognized and

parsed.

The other data import functions in `readr` will produce similar results.

# Data Manipulation

## A Note on Tidy Data

I'm going to take a brief minute here to discuss "tidy" data. The idea behind

tidy data is similar to normalization in databases and indeed tidy data can be

thought of as a re-casting of 3rd Normal Form in a statistical language.

Specifically,

1. Each variable must have its own column;

2. Each observation must have its own row;

3. Each value must have its own cell.

If the data is stored as such, it makes manipulating it and producing summaries,

aggregations and other data transformations easier. It also means the data is

stored consistently and do you don't have to re-learn the data structure every

project.

The tools in the tidyverse are designed around the idea of tidy data and

integrate neatly with the concept. If you have tidy data, use of these tools

will feel natural and intuitive.

All of the data sets that we have are tidy, but if they aren't (or you just

need to do it) the functions `gather()` and `spread()` from the `tidyr`

package (part of the tidyverse) are useful. `gather()` takes "wide" data and

makes it long. For instance,

```{r spread_and_gather}

stocks <- tibble(

time = as.Date('2009-01-01') + 0:9,

X = rnorm(10, 0, 1), # just generates some random numbers

Y = rnorm(10, 0, 2), # just generates some random numbers

Z = rnorm(10, 0, 4) # just generates some random numbers

)

stocks

```

is the closing price of 3 stocks "X", "Y" and "Z" at the end of each day

from 2009-1-1 to 2009-1-10. If we wanted them to be long such that there

was 3 rows for each time, a column that indicates the stock and a column that

indicates the closing price, we would use `gather()`. `gather()` typically takes

4 arguments: `data` is the name of the tibble to perform the operation on,

`key` is the name to use for the column that will become the key, `value`

is the name to use for the column that will hold the value then a comma

separated list of variables to include (or prefix with a `-` sign to exclude).

For the `stocks` example

```{r gather_1}

stocks_wide <- gather(stocks, stock, closing_price, -time)

stocks_wide

```

and we can convert back to wide using `spread()`. This reverses the action of

`gather()`. The first argument should be the name of the tibble to act on

(in this case `stocks_wide`), the second should be the name of the column that

contains the values to use as the new column names (`stocks`) and the third

should contain the values used to fill the new cells (`closing_price`).

```{r}

spread(stocks_wide, stock, closing_price)

```

These are handy little tools to keep in your tool kit. Moving from wide-to-long

happens more than you'd expect.

For more on tidy data, its importance and how it works influences the

`tidyverse` see [R for Data Science Chapter 12](http://r4ds.had.co.nz/tidy-data.html).

## The `dplyr` Verbs

`dplyr` is a workhorse package to manipulating and summarizing data. The most

exciting thing about `dplyr` is that the syntax and code is the same for

working on an in-memory dataset (like we do here) or a SQL database. `dbplyr`

is a package that extends `dplyr` and converts your R code into SQL queries

and passes them off to the RDBMS. This is really cool when you are working with

large data sets and makes the transition between in-memory data manipulation and

on-disk data manipulation seamless. It is also very easy to use, which doesn't

hurt at all!

In general, `dplyr` is simply a collection of six verbs (or five verbs and one

adverb) which will do about 99% of all data manipulation tasks you might want to

do. The verbs are

* `select()`

* `filter()`

* `mutate()`

* `summarize()`

* `arrange()`

* `group_by()` (this might actually be an adverb)

We'll go through what each function does and how to use it using the

`nycflights13` data sets as an example.

### `select()`

Select does what it says - it selects things. You give it the name of a data

object and then a comma separated list of variables and it returns the data

object with only those variables.

Let's start with the `airports` table

```{r vars_in_flights}

airports

```

We might only want the `air_time` (flight time) and `distance` in our dataset.

The rest of the variables are just taking up space. We can use `select()` to

do that for us

```{r select_1}

select(airports, faa, lat, lon)

```

We can also exclude specific variables by putting a `-` in front of the variable

name

```{r select_2}

select(airports, -faa)

```

We can also use a set of helper functions to select the desired variables:

* `starts_with(match)` - returns any variables that start with the value passed

as `match`

* `ends_with(match)` - returns any variables that ends with the value passed as

`match`

* `contains(match)` - returns any variables that contain the value `match`

#### Exercises

1. Arrange the data by the distance covered by the flight

### `filter()`

`filter()` filters things. It takes as a first argument the name of the data

object (a tibble or data.frame) to filter and then a series of comma separated

expressions that evaluate to logical TRUE/FALSE statements about a given row.

The `flights` table is a good place to try this:

```{r filter_1}

flights

```

Suppose we wanted to find it any flight from NYC went to Des Moines airport

in 2013. The expression would test if `dest == "DSM"`. So

```{r filter_2}

filter(flights, dest == "DSM")

```

Suppose we wanted multiple filtering rules, we can string them together with

commas and `filter()` understands that as "AND". So `filter(data, x, y)` means

return rows in data where both x AND y are true.

```{r filter_3}

filter(flights, year == 2013, month == 1, day == 1)

```

You can join using "OR" as well. In R, the logical operator OR is expressed as

`|`. For instance, if I want to find flights that left either more than 5

minutes before or 5 minutes after their scheduled time, I would run

```{r filter_4}

filter(flights, (dep_time - sched_dep_time) >= 5 | (dep_time - sched_dep_time) <= -5)

```

which differs from separating with a comma

```{r filter_5}

filter(flights, (dep_time - sched_dep_time) >= 5, (dep_time - sched_dep_time) <= -5)

```

which returns zero rows (no flight can leave both 5 minutes before and 5 minutes

after the scheduled time).

Filter also works to when using functions in the logical statement. We could

find the longest distance flight on May 27th using

```{r filter_6}

filter(flights, month == 5, day == 27, distance == max(distance, na.rm = TRUE))

```

#### Exercises

From R for Data Science Chapter 5

Find all flights that:

1. Arrived 2 or more hours late

2. Flew to DSM or OMA

3. Operated by UA, AA or DL

4. Arrived more than 2 hours late but didn't leave late

5. Delayed in leaving by at least 1 hour but made up 30 hours in flight

### `mutate()`

`mutate` is used to add new variables to a tibble. As with the other verbs

so far, the first argument is the name of the tibble to mutate followed by a

comma separated list of variables and the values to assign to those variables.

The assignment is done in the form `variable_name = value`.

The `flights` table contains information about the flight time and distance

but does not include the speed. We could combine the air time and the distance

to estimate speed. Let's do that:

```{r mutate_1}

flights <- mutate(flights, speed = distance / (air_time / 60))

```

And now if we view flights, we'll see a new variable called speed:

```{r mutate_2}

select(flights, distance, air_time, speed)

```

Multiple variables can be constructed inside a single `mutate()` call:

```{r}

flights <- mutate(flights,

dep_delay = dep_time - sched_dep_time,

arr_delay = arr_time - sched_arr_time)

select(flights, dep_delay, arr_delay)

```

### `summarize()`

`summarize()` takes as the first argument, you guessed it, the data object and

the following arguments are in the same manner as with mutate. While `mutate()`

must returns an $n$ row column, `summarize()` must return a 1 row column that

is a summary measure (e.g., mean, sd, median). If we wanted to get an idea of

the mean and standard deviation of the arrival delays, we would use

```{r summarize_1}

# na.rm = TRUE just means ignore rows where there is a missing value

summarize(flights,

mean_arrival_delay = mean(arr_delay, na.rm = TRUE),

sd_arrival_delay = sd(arr_delay, na.rm = TRUE))

```

The average flight arrives 6.9 minutes late with a standard deviation of 44.6

minutes.

### `arrange()`

`arrange()` is used to order data by a variable in the data. For instance,

if we wanted to order the `flights` table by the the departure time, we would

run

```{r arrange_1}

arrange(flights, dep_time)

```

and we get a bunch of flights that left at 00:01.

### `group_by()`

The major value of `dplyr` comes with the `group_by` function when combined with

the prior verbs. `group_by` modifies the prior verbs so that they operate on a

group basis. For instance, if we wanted the mean arrival delay by airline,

```{r group_by_1}

flights <- group_by(flights, carrier)

```

You'll notice that `flights` doesn't look much different if you print it

```{r group_by_2}

flights

```

but in the console you'll see the new line that says:

```

# Groups: carrier [16]

```

this indicates that `flights` is now a grouped tibble and the groups are

given by the value of `carrier`. If we apply one of the earlier functions

to `flights` now, such as the summarize function, we'll get a value returned

for each of the groups.

```{r group_by_3}

summarize(flights, mean_arrival_delay = mean(arr_delay, na.rm = TRUE))

```

We can also group by several variables. For instance, maybe flights to one

airport are more delayed than others and there is also a carrier effect. We

would want to group both by carrier and by destination airport:

```{r group_by_4}

flights <- group_by(flights, carrier, dest)

summarize(flights, mean_arrival_delay = mean(arr_delay, na.rm = TRUE))

```

Earlier in the `filter()` examples, we used `filter()` to find the furthest

distance a flight covered. We could do the same trick with `filter()` and

`group_by()` to find the longest-distance flight on each carrier.

```{r group_by_5}

flights <- group_by(flights, carrier)

filter(flights, distance == max(distance))

```

Why is this 12,793 rows and not 16? Multiple flights for the same carrier have

the same distance (e.g., the same route appears several times).

## The Pipe Operator `%>%`

This example is motivated/adapted from R for Data Science.

Imagine the following nursery rhythm:

Little bunny Foo Foo

Went hopping through the forest

Scooping up the field mice

And bopping them on the head

We could code this as:

```

foo_foo <- little_bunny()

foo_foo_1 <- hop(foo_foo, through = forest)

foo_foo_2 <- scoop(foo_foo_1, up = field_mice)

foo_foo_3 <- bop(foo_foo_2, on = head)

```

but that is hard to debug, write and understand. The intermediate steps don't

have clear value, they clutter your workspace and invite error with making

the suffix unique.

You could re-write it so that you simply overwrite the original object in

each step:

```

foo_foo <- little_bunny()

foo_foo <- hop(foo_foo, through = forest)

foo_foo <- scoop(foo_foo, up = field_mice)

foo_foo <- bop(foo_foo, on = head)

```

but this is still hard to read and debug. How do you know when something went

wrong with `foo_foo` is the output is just something is wrong with `foo_foo`?

You could do a lot of nesting of function calls:

```

foo_foo <- little_bunny()

bop(

scoop(

hop(foo_foo, through = forest),

up = field_mice

),

on = head

)

```

but this is confusing because the argument `on` belongs to `bop()` but is

5 lines from the opening of `bop()`.

This rapidly becomes a problem - imagine a typical data summarization step that

involves filtering the data, making a transformation, grouping the data,

making the summary measure and arranging by some value. You'd end up with

```{r pipe_1}

arrange(

summarize(

group_by(

mutate(

filter(flights, origin == "JFK"),

speed = distance / (air_time / 60)),

carrier),

mean_speed = mean(speed, na.rm = TRUE)),

carrier, mean_speed)

```

And that makes about zero sense. It runs but it is confusing to code and

confusing to understand. Instead, it would be amazing to do this naturally with

a "then" type ordering. This is what the `%>%` (pipe) does.

Simply put a pipe takes the results of a function and uses them as the first

argument of the following function. We could re-write the story about Foo Foo

using pipes as

```

foo_foo %>%

hop(through = forest) %>%

scoop(up = field_mouse) %>%

bop(on = head)

```

This is a logical ordering, easy to understand, keeps functions and their

arguments tightly linked and follows naturally.

The data summarization example above can be recast simply as

```{r pipe_2}

flights %>%

filter(origin == "JFK") %>%

mutate(speed = distance / (air_time / 60)) %>%

group_by(carrier) %>%

summarize(mean_speed = mean(speed, na.rm = TRUE)) %>%

arrange(carrier, mean_speed)

```

It gives the same results but is much easier to understand. Since nearly all

data analysis and manipulations are a linear flow from unstructured/messy data

to rectangular data to tidy data to transformations to models, the concept of

"then" as a glue between the steps comes naturally.

## Joins

Typically, data exists in several tables and we would like to merge the data

together into a single table for our analysis. `dplyr` supports a number of

joins. They are:

* `inner_join(x, y)` returns the rows from that exist in both `x` and `y` with

all the values from `x` and `y`

* `left_join(x, y)` returns all the rows in that exist in `x` with the

values from `x` and `y`. If rows exist in `x` but don't have a match in

`y` have their values set to missing (`NA`)

* `right_join(x, y)` is the same as `left_join()` but keeps all the rows in

`y` instead of `x`

* `full_join(x, y)` keeps all the rows and values that occur in either `x` or

`y`

* `semi_join(x, y)` returns all the rows in `x` that have a matching row in `y`

but does not include any variables from `y`

* `anti_join(x, y)` returns all the rows in `x` that do not have a matching row

in `y`

By default, `*_join()` will use all the variables common to `x` and `y` when

performing the join. This behavior can be over-ridden by setting the `by`

argument, see the Arguments section for `inner_join()` for details on how to

do this (hint: `?inner_join`).

We might want to take the data from the `flights` table and merge in the

information about the type and number of engines for each plane. The `flights`

table contains the `tailnum` of the plane that made the flight. The `planes`

table contains more information about that plane. We want to join `flights`

and `planes`, compute average speed and then group that by engine type and

the number of engines and calculate the mean.

```{r joins_1}

mean_speed_by_engine_type_and_number <- flights %>%

ungroup() %>%

select(tailnum, air_time, distance) %>%

inner_join(planes) %>%

select(air_time, distance, engines, engine) %>%

group_by(engine_type = engine, engine_number = engines) %>%

summarize(mean_speed = mean(distance / (air_time / 60),

na.rm = TRUE))

mean_speed_by_engine_type_and_number

```

#### Exercises

How might you find the average and median arrival delay by carrier?

# Visualization

For more information see

[Chapter 3 of R for Data Science](http://r4ds.had.co.nz/data-visualisation.html)

We are going to focus on using `ggplot2` for our plots. The basic use is to

call the function `ggplot(data, mapping = aes())` where data is some

data object (e.g., tibble) and the mapping contains some of the aesthetics

for the plot (e.g., what values should be plotted along the x and y, is there

some grouping in the data that you want to show with color or line or point

type).

After initializing the `ggplot` object with that call, you append `geom`s to

the plot with the `+` operator. For instance, the `geom_point()` produces a

scatter plot of the data set to `x` and `y` in the `mapping` of the

call to `ggplot`. As an example,

```{r vis_1}

ggplot(flights, aes(x = dep_delay, y = arr_delay)) +

geom_point()

```

We might want to color the data points by the carrier

```{r vis_2}

ggplot(flights, aes(x = dep_delay, y = arr_delay, color = carrier)) +

geom_point()

```

We can even combine plots with data manipulations connected through pipes:

```{r vis_3}

flights %>%

inner_join(weather) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = wind_dir,

y = dep_delay,

color = origin)) +

geom_point()

```

This is an interesting plot but hard to understand since the data from the

3 airports are plotted on top of each other. We might want to break those

apart by using what is called a facet or `facet_wrap()` in our plot building

command. `facet_wrap()` takes as its first argument a one-sided formula that

tells it which variable to use to construct the facets. For example,

```{r vis_3b}

flights %>%

inner_join(weather) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = wind_dir,

y = dep_delay,

color = origin)) +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(~ origin)

```

We can also do things like putting in a smoother to show with the data:

```{r vis_4}

flights %>%

inner_join(weather) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = wind_dir,

y = dep_delay,

color = origin)) +

geom_smooth() +

facet_wrap(~ origin)

```

We didn't pass the argument `method` in `geom_smooth()` and so it defaulted to

using a GAM smoother which is a locally-weighted smoother that performs well

and fast on large data sets. For small data sets, it defaults to `loess` which

is a similar idea as GAM but slower. You can also tell `geom_smooth()` what

type of smoother to use (e.g., `lm` for linear model for a line-of-best-fit).

You might think that the data is describing a circle - 360 and 0 degrees are

the same direction - and wouldn't it be nice if the data was shown with

the x variable forming a circle? We can convert the data to be shown in a

polar coordinate system instead of an Cartesian system by adding `coord_polar()`

to the statement that builds the model:

```{r vis_5}

flights %>%

inner_join(weather) %>%

group_by(origin, wind_dir = round(wind_dir)) %>%

summarize(dep_delay = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = wind_dir,

y = dep_delay,

color = origin)) +

geom_point() +

geom_path() +

facet_wrap(~ origin) +

coord_polar()

```

We can take the same graph and improve the labeling or change the theme as

well. The `labs()` argument is used to set the labels for the axis of the plot

while there are a number of themes built-in such as `theme_bw()` or

`theme_minimal()`. Custom themes can be built with the `theme()` function and

the package [`ggthemes`](https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggthemes/vignettes/ggthemes.html)

provides a variety of themes you might want to use.

```{r vis_6}

flights %>%

inner_join(weather) %>%

group_by(origin, wind_dir = round(wind_dir)) %>%

summarize(dep_delay = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = wind_dir,

y = dep_delay,

color = origin)) +

geom_point() +

geom_path() +

facet_wrap(~ origin) +

coord_polar() +

labs(x = "Wind Direction", y = "Depature Delay")

```

You can even generate maps in `ggplot2` but this requires that you install

the package `mapproj` as well.

```{r vis_7}

ggplot(airports, aes(x = lon, y = lat)) +

geom_point(size = 0.5) +

borders()

```

# Regression

For more information, see the

[Model Building Chapter in R for Data Science](http://r4ds.had.co.nz/model-building.html)

Regression is the main way in which we estimate the effect of some variable(s)

$X$ on some outcome $y$. You've probably heard of linear regression (line of

best fit). There are other methods known as generalized linear models (GLM)

that are commonly used regression methods as well. These are used when the

response variable has special properties - such as being binary (yes/no,

disease/no disease) or counts. Aaron will talk about logistic regression

next week which is a case of GLM and he will use the `glm()` function.

The syntax does not vary according to the desired model in `glm()`, you just

change the desired family.

In R, a model is estimated by selecting the function we will use to do the

estimation (in this case `glm()`) and then providing a formula that describes

the model. Typically, inside a call to `glm()` you will use 2 or 3

arguments. They are

* formula (first) - the specification of the model you want to estimate. A

formula is written in the form `<response> ~ <x>` in the most

simple case. A more complicated model that includes several possible predictors

is written as `<response> ~ <x1> + <x2> + ... + <xk>`. You can include

transformations in the formula (e.g., `log` or `sqrt`). R will process the

formula and build the model matrix (e.g., it handles construction of dummy

variables for you).

* family (second) - the distribution of the response data. You'll probably

either leave this as the default `gaussian()` for classic linear models or

`binomial()` for binary response data.

* data (third) - the data set to use to estimate the model

For example, we might want to know how the arrival delay is affected by the

departure delay. We would regress the arrival delay in `flights` on the

departure delay to decompose the arrival delay into the portion that is caused

by departure delays and the portion caused by other factors. The data set

we would want to use is `flights`, the model would be `arr_delay ~ dep_delay`

and we can leave the family as `guassian()`. The model building step would

look like:

```{r regression_1}

model <- glm(arr_delay ~ dep_delay,

data = flights)

```

If we want to see a summary of the model fit with hypothesis tests, we would use

the `summary()` function (`summary(x)` applied to nearly any object in R will

produce a summary of `x` that varies based on what `x` is. In this case,

`x` is a model and so it provides a summary of the model fit but if `x` was a

data.frame/tibble, it would provide a variable-by-variable summary including

the min, 1st, 2nd, 3rd quartiles, mean and max.).

```{r regression_2}

summary(model)

```

The `summary(model)` says that a flight that leaves on time arrives about 6

minutes earlier that scheduled and that for each minute that the flight is

delayed compared to the scheduled departure time there is a 1.02 minute delay

on arrival.

# Functional Programming (Probably Won't Get to)

For more detail see [R for Data Science Chapter 25](http://r4ds.had.co.nz/many-models.html).

One of the most powerful things about the tidyverse is the ability do construct

"list-columns" inside a tibble. There look like and behave like normal columns

but instead of containing an atomic value, they contain a tibble. You construct

these with the `nest()` command and the nesting is done by the groups of the

tibble. For instance, if I wanted to nest the data by airline and airport,

I would

```{r nest_1}

nested_flights <- flights %>%

group_by(carrier, origin) %>%

nest()

nested_flights

```

Notice how `carrier` and `origin` are both columns of vectors but the new

variable `data` is a tibble. That tibble contains only the rows of data for that

row's `carrier` and `origin` values.

You can interact with that data using the `purrr` package. For instance, if

we wanted to fit a model that predicted the probability of a plane leaving

late based on the number of flights out, the month, day-of-week, wind speed,

hour and flight distance with a different model for each airline and airport

we could do something like this:

```{r nest_2}

weather_and_time <- flights %>%

ungroup() %>%

inner_join(weather) %>%

select(carrier, origin,

dep_delay,

year, month, day, hour,

wind_speed, distance)

number_of_flights <- flights %>%

group_by(origin, year, month, day, hour) %>%

summarize(number_of_flights_hour = n())

model_data <- inner_join(weather_and_time, number_of_flights) %>%

mutate(day_of_week = as.factor(lubridate::wday(lubridate::ymd(paste(year, month, day)))),

month = as.factor(month)) %>%

select(-year, -day)

model_data

model_data <- model_data %>%

group_by(carrier, origin) %>%

nest() %>%

filter(carrier %in% c("AA", "UA", "DL"))

model_data

model_data <- model_data %>%

mutate(model = purrr::map(data, ~ lm(dep_delay ~ ., data = .)))

model_data

```

We now have a column named `model` that contains a series of 35 linear models.

We can see that these are models if we select the vector and print the first

element:

```{r}

model_data$model[[1]]

```

We can use the `broom` package to extract the estimated coefficients of the

model and see if the different airlines have different sensitivities to the

number of flights out of the airport:

```{r}

sensitivity_to_congestion <- model_data %>%

mutate(sens_to_congestion = purrr::map(model,

~ broom::tidy(.) %>%