Thanks for Cherno's C++ series. It actually helps me a lot. This series not only helps me learn how C++ works, but also improves my English level. Cherno speeks so fast, firstly I have to learn it by subtitles, then I try to just listen and Markdown, but I still miss some information. So for some vital stuff, I have to listen it two or three times. As the consequence, it helps me understand it deeply and improve my poor English.

I try to use python crawler and Regular expression to obtain the course list as follows:

course list

- "Welcome to C++"

- "How to Setup C++ on Windows"

- "How to Setup C++ on Mac"

- "How to Setup C++ on Linux"

- "How C++ Works"

- "How the C++ Compiler Works"

- "How the C++ Linker Works"

- "Variables in C++"

- "Functions in C++"

- "C++ Header Files"

- "How to DEBUG C++ in VISUAL STUDIO"

- "CONDITIONS and BRANCHES in C++ (if statements)"

- "BEST Visual Studio Setup for C++ Projects!"

- "Loops in C++ (for loops, while loops)"

- "Control Flow in C++ (continue, break, return)"

- "POINTERS in C++"

- "REFERENCES in C++"

- "CLASSES in C++"

- "CLASSES vs STRUCTS in C++"

- "How to Write a C++ Class"

- "Static in C++"

- "Static for Classes and Structs in C++"

- "Local Static in C++"

- "ENUMS in C++"

- "Constructors in C++"

- "Destructors in C++"

- "Inheritance in C++"

- "Virtual Functions in C++"

- "Interfaces in C++ (Pure Virtual Functions)"

- "Visibility in C++"

- "Arrays in C++"

- "How Strings Work in C++ (and how to use them)"

- "String Literals in C++"

- "CONST in C++"

- "The Mutable Keyword in C++"

- "Member Initializer Lists in C++ (Constructor Initializer List)"

- "Ternary Operators in C++ (Conditional Assignment)"

- "How to CREATE/INSTANTIATE OBJECTS in C++"

- "The NEW Keyword in C++"

- "Implicit Conversion and the Explicit Keyword in C++"

- "OPERATORS and OPERATOR OVERLOADING in C++"

- "The "this" keyword in C++"

- "Object Lifetime in C++ (Stack/Scope Lifetimes)"

- "SMART POINTERS in C++ (std::unique_ptr, std::shared_ptr, std::weak_ptr)"

- "Copying and Copy Constructors in C++"

- "The Arrow Operator in C++"

- "Dynamic Arrays in C++ (std::vector)"

- "Optimizing the usage of std::vector in C++"

- "Using Libraries in C++ (Static Linking)"

- "Using Dynamic Libraries in C++"

- "Making and Working with Libraries in C++ (Multiple Projects in Visual Studio)"

- "How to Deal with Multiple Return Values in C++"

- "Templates in C++"

- "Stack vs Heap Memory in C++"

- "Macros in C++"

- "The "auto" keyword in C++"

- "Static Arrays in C++ (std::array)"

- "Function Pointers in C++"

- "Lambdas in C++"

- "Why I don't "using namespace std""

- "Namespaces in C++"

- "Threads in C++"

- "Timing in C++"

- "Multidimensional Arrays in C++ (2D arrays)"

- "Sorting in C++"

- "Type Punning in C++"

- "Unions in C++"

- "Virtual Destructors in C++"

- "Casting in C++"

- "Conditional and Action Breakpoints in C++"

- "Safety in modern C++ and how to teach it"

- "Precompiled Headers in C++"

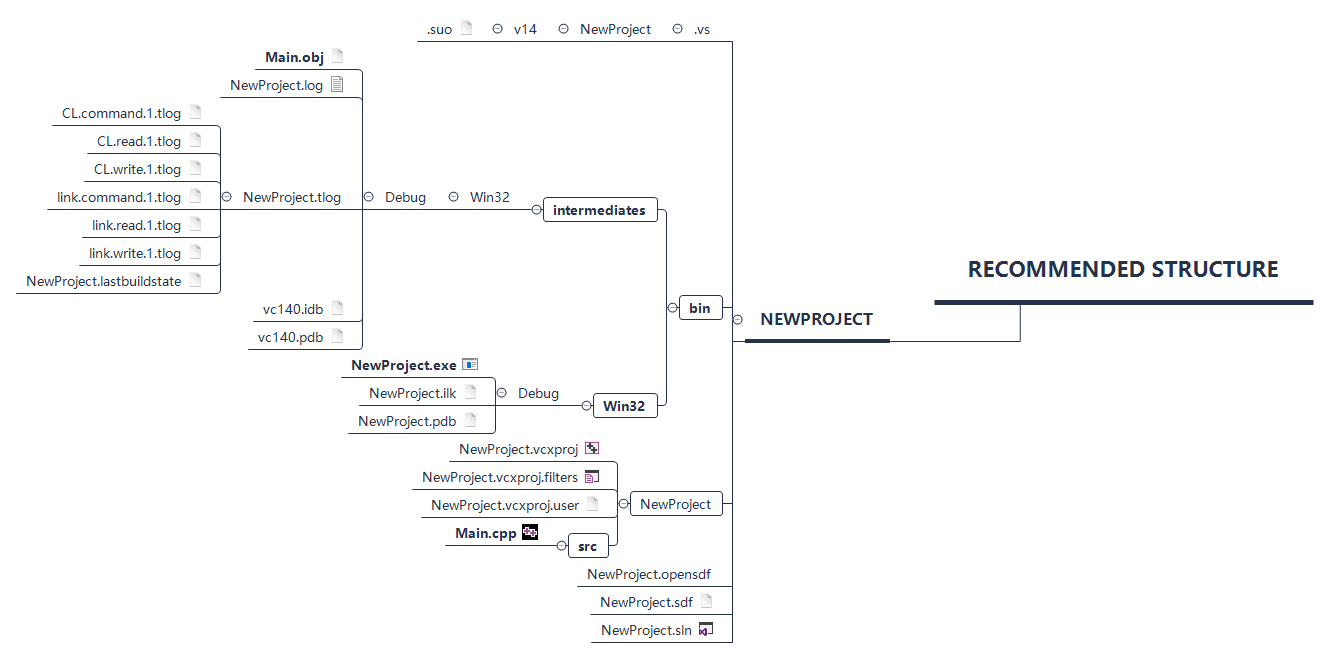

- NewProject

- Youtube

- Date: 2019-1-19

- Date: 2019-1-17

- Date: 2019-1-10

- Date: 2019-1-9

- Date: 2019-1-8

- Date: 2019-1-7

- Date: 2019-1-6

- Date: 2019-1-5

- Date: 2019-1-4

- Date: 2018-12-29

- Date: 2018-12-28

- Date: 2018-12-27

- Date: 2018-12-26

- Date: 2018-12-25

- Date: 2018-12-24

- Date: 2018-12-23

- Date: 2018-12-22

- Date: 2018-12-21

- Date: 2018-12-20

- Date: 2018-12-19

- Date: 2018-12-18

- Date: 2018-12-17

- Date: 2018-12-16

- Date: 2018-12-15

- Date: 2018-12-14

- Date: 2018-12-13

- Date: 2018-12-12

It provides a recommended VS Directory Structure as follows:

Java was designed to be platform independent, while C/C++ was platform dependent.

rules for making variables:

- only alphabetic characters, digits and underscore is permitted.

- variable name cannot start with digits

- uppercase and lowercase characters are distinct

that means,

int dataandint Dataare not the same thing - C++ keywords cannot be variable name

signed,unsigned,longandshortare used only beforeintandchar.doubleforfloat. Also, you can only uselong double.- you cannot write

double float.

break

Causes the enclosing for, range-for, while or do-while loop or switch statement to terminate.

Used when it is otherwise awkward to terminate the loop using the condition expression and conditional statements.

After this statement the control is transferred to the statement immediately following the enclosing loop or switch. (break 跳出当前所属loop或者switch的后花括号之后)

A break statement cannot be used to break out of multiple nested loops.(break一次只能跳出一层循环)

continue

Causes the remaining portion of the enclosing for, range-for, while or do-while loop body to be skipped.

Used when it is otherwise awkward to ignore the remaining portion of the loop using conditional statements. (遇continue跳到紧邻的下次循环条件)

returnwith an optional expression,using list initialization

Terminates the current function and returns the specified value (if any) to its caller. (遇到return跳转到函数的后花括号

}之前,忽视return后续的语句)

Some special cases:

-

If control reaches the end of a function with the return type

void(possibly cv-qualified), end of a constructor, end of a destructor, or the end of a function-try-block for a function with the return type (possibly cv-qualified)voidwithout encountering a return statement, return; is executed.(cv-qualified 指的是可被const,volatile关键字修饰)

(void作为函数返回数据类型,返回值由implicit conversion得到,即

return;) -

If control reaches the end of the main function,

return 0; is executed.(入口函数

main,默认添加return 0;的隐式转换)Flowing off the end of a value-returning function (except main) without a return statement is undefined behavior. (非void返回类型函数,也非main函数,没有返回值将被视为未定义行为)

-

In a function returning void, the return statement with expression can be used, if the expression type is void.

-

Returning by value may involve construction and copy/move of a temporary object, unless copy elision is used. Specifically, the conditions for copy/move can be found here

goto

Transfers control unconditionally. (无条件控制转移)

Used when it is otherwise impossible to transfer control to the desired location using other statements.

无条件跳转到label处

Reference:

std::pair将两种数据类型组合在一起,比如组合两个数据为一组,或者key-value的形式

Preprocessor directives are lines included in the code of programs preceded by a hash sign (#). These lines are not program statements but directives for the preprocessor. The preprocessor examines the code before actual compilation of code begins and resolves all these directives before any code is actually generated by regular statements.

These preprocessor directives extend only across a single line of code. As soon as a newline character is found, the preprocessor directive is ends. No semicolon (;) is expected at the end of a preprocessor directive. The only way a preprocessor directive can extend through more than one line is by preceding the newline character at the end of the line by a backslash ().

I have been struggling with the concepts of lvalue and rvalue in C++ since forever. I think that now is the right time to understand them for good, as they are getting more and more important with the evolution of the language.

Once the meaning of lvalues and rvalues is grasped, you can dive deeper into advanced C++ features like move semanticsand rvalue references (more on that in future articles).

Lvalues and rvalues: a friendly definition

Firts of all, let's keep our heads away from any formal definition. In C++ an lvalue is something that points to a specific memory location. On the other hand, a rvalue is something that doesn't point anywhere. In general, rvalues are temporary and short lived, while lvalues live a longer life since they exist as variables. It's also fun to think of lvalues as containers and rvalues as things contained in the containers. Without a container, they would expire.

Let me show you some examples right away.

int x = 666; // okHere

666is an rvalue; a number (technically a literal constant) has no specific memory address, except for some temporary register while the program is running. That number is assigned tox, which is a variable. A variable has a specific memory location, so its an lvalue. C++ states that an assignment requires an lvalue as its left operand: this is perfectly legal.Then with

x, which is an lvalue, you can do stuff like that:int* y = &x; // okHere I'm grabbing the the memory address of

xand putting it intoy, through the address-of operator&. It takes an lvalue argument and produces an rvalue. This is another perfectly legal operation: on the left side of the assignment we have an lvalue (a variable), on the right side an rvalue produced by the address-of operator.However, I can't do the following:

int y; 666 = y; // error!Yeah, that's obvious. But the technical reason is that

666, being a literal constant — so an rvalue, doesn't have a specific memory location. I am assigningyto nowhere.This is what GCC tells me if I run the program above:

error: lvalue required as left operand of assignmentHe is damn right; the left operand of an assigment always require an lvalue, and in my program I'm using an rvalue (

666).I can't do that too:

int* y = &666; // error!GCC says:

error: lvalue required as unary '&' operand`He is right again. The

&operator wants an lvalue in input, because only an lvalue has an address that&can process.Functions returning lvalues and rvalues

We know that the left operand of an assigment must be an lvalue. Hence a function like the following one will surely throw the

lvalue required as left operand of assignmenterror:int setValue() { return 6; } // ... somewhere in main() ... setValue() = 3; // error!Crystal clear:

setValue()returns an rvalue (the temporary number6), which cannot be a left operand of assignment. Now, what happens if a function returns an lvalue instead? Look closely at the following snippet:int global = 100; int& setGlobal() { return global; } // ... somewhere in main() ... setGlobal() = 400; // OKIt works because here

setGlobalreturns a reference, unlikesetValue()above. A reference is something that points to an existing memory location (theglobalvariable) thus is an lvalue, so it can be assigned to. Watch out for&here: it's not the address-of operator, it defines the type of what's returned (a reference).The ability to return lvalues from functions looks pretty obscure, yet it is useful when you are doing advanced stuff like implementing some overloaded operators. More on that in future chapters.

Lvalue to rvalue conversion

An lvalue may get converted to an rvalue: that's something perfectly legit and it happens quite often. Let's think of the addition

+operator for example. According to the C++ specifications, it takes two rvalues as arguments and returns an rvalue.Let's look at the following snippet:

int x = 1; int y = 3; int z = x + y; // okWait a minute:

xandyare lvalues, but the addition operator wants rvalues: how come? The answer is quite simple:xandyhave undergone an implicit lvalue-to-rvalue conversion. Many other operators perform such conversion — subtraction, addition and division to name a few.Lvalue references

What about the opposite? Can an rvalue be converted to lvalue? Nope. It's not a technical limitation, though: it's the programming language that has been designed that way.

In C++, when you do stuff like

int y = 10; int& yref = y; yref++; // y is now 11you are declaring

yrefas of typeint&: a reference toy. It's called an lvalue reference. Now you can happily change the value ofythrough its referenceyref.We know that a reference must point to an existing object in a specific memory location, i.e. an lvalue. Here

yindeed exists, so the code runs flawlessly.Now, what if I shortcut the whole thing and try to assign

10directly to my reference, without the object that holds it?int& yref = 10; // will it work?On the right side we have a temporary thing, an rvalue that needs to be stored somewhere in an lvalue.

On the left side we have the reference (an lvalue) that should point to an existing object. But being

10a numeric constant, i.e. without a specific memory address, i.e. an rvalue, the expression clashes with the very spirit of the reference.If you think about it, that's the forbidden conversion from rvalue to lvalue. A volatile numeric constant (rvalue) should become an lvalue in order to be referenced to. If that would be allowed, you could alter the value of the numeric constant through its reference. Pretty meaningless, isn't it? Most importantly, what would the reference point to once the numeric value is gone?

The following snippet will fail for the very same reason:

void fnc(int& x) { } int main() { fnc(10); // Nope! // This works instead: // int x = 10; // fnc(x); }I'm passing a temporary rvalue (

10) to a function that takes a reference as argument. Invalid rvalue to lvalue conversion. There's a workaround: create a temporary variable where to store the rvalue and then pass it to the function (as in the commented out code). Quite inconvenient when you just want to pass a number to a function, isn't it?Const lvalue reference to the rescue

That's what GCC would say about the last two code snippets:

error: invalid initialization of non-const reference of type 'int&' from an rvalue of type 'int'GCC complains about the reference not being const, namely a constant. According to the language specifications, you are allowed to bind a const lvalue to an rvalue. So the following snippet works like a charm:

const int& ref = 10; // OK!And of course also the following one:

void fnc(const int& x) { } int main() { fnc(10); // OK! }The idea behind is quite straightforward. The literal constant

10is volatile and would expire in no time, so a reference to it is just meaningless. Let's make the reference itself a constant instead, so that the value it points to can't be modified. Now the problem of modifying an rvalue is solved for good. Again, that's not a technical limitation but a choice made by the C++ folks to avoid silly troubles.This makes possible the very common C++ idiom of accepting values by constant references into functions, as I did in the previous snipped above, which avoids unnecessary copying and construction of temporary objects.

Under the hood the compiler creates an hidden variable for you (i.e. an lvalue) where to store the original literal constant, and then bounds that hidden variable to your reference. That's basically the same thing I did manually in a couple of snippets above. For example:

// the following... const int& ref = 10; // ... would translate to: int __internal_unique_name = 10; const int& ref = __internal_unique_name;Now your reference points to something that exists for real (until it goes out of scope) and you can use it as usual, except for modifying the value it points to:

const int& ref = 10; std::cout << ref << "\n"; // OK! std::cout << ++ref << "\n"; // error: increment of read-only reference ‘ref’Conclusion

Understanding the meaning of lvalues and rvalues has given me the chance to figure out several of the C++'s inner workings. C++11 pushes the limits of rvalues even further, by introducing the concept of rvalue references and move semantics, where — surprise! — rvalues too are modifiable. I will restlessly dive into that minefield in one of my next articles.

C style cast and C++ style cast, there are four types of cast in C++, they are:

static cast,reinterpret cast,dynamic castandconst cast. C style cast can achieve all of those above casts

More examples and definitions can be found here.

Visual Studio provides powerful breakpoints to help developers debug their codes. Here is a documentation of how to use breakpoint in Visual Studio.

precompiled header files, abbreviated as "PCH". Image that you are using a buntch of header files, they just perform copy and paste in the main function, but each time we modify our source code, we have to recompile it, thus it costs long time for us to compile header file. So here is the motivation. We can simply precompiled these header files into one binary file, if we are not gonna frequently change them, so the speed will increase a lot. Cases like standard template library, Windows API and so on.

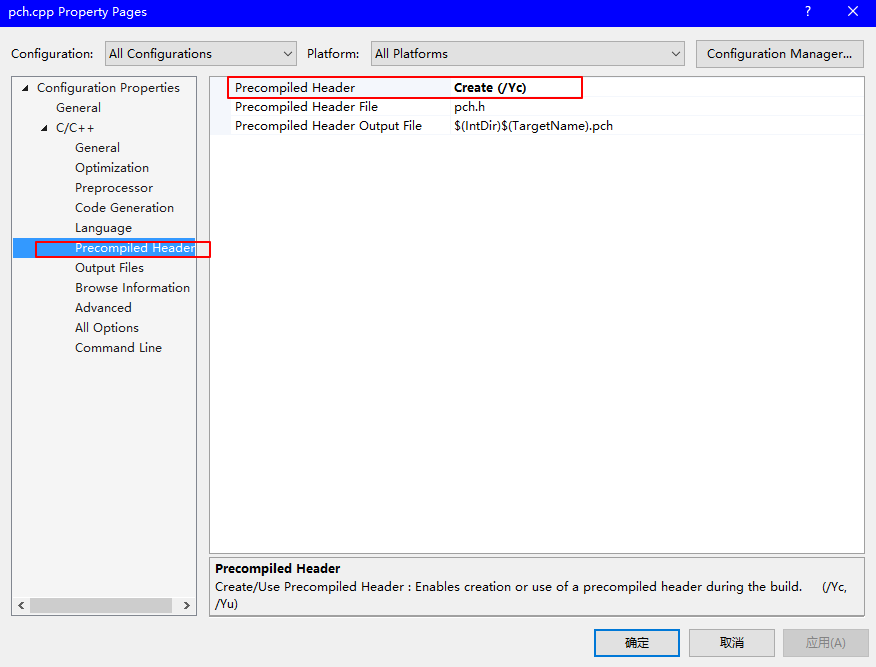

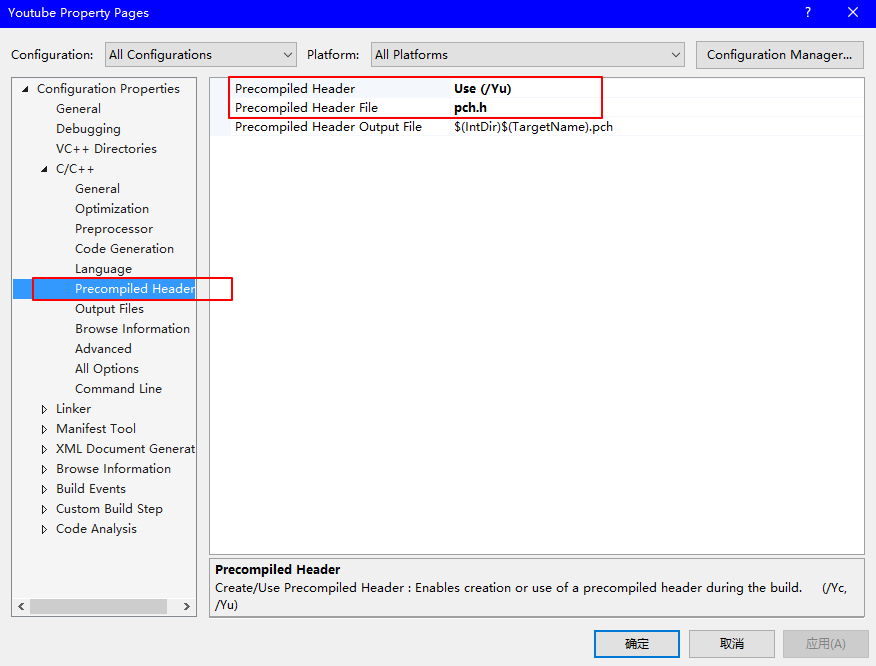

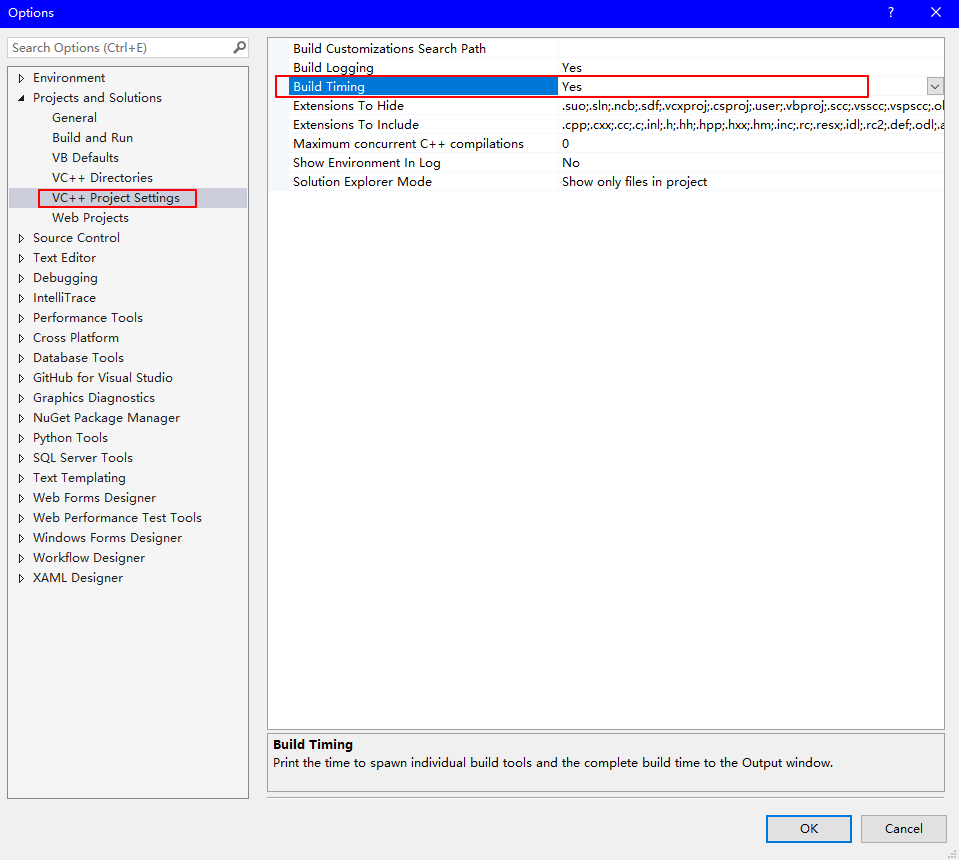

To achieve all of these, you need some Visual Studio settings as follows:

- copy not frequently modified header files in one cpp file, eg.

pch.cpp - set

pch.cppproperty as - set the whole project property as

- click Tools-> Options to calculate build timing as

The time difference of using precompiled header file or not can be found in the following table:

| using PCH | first test | make some changes | second tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| yes | 1572ms | yes | 428ms |

| no | 2326ms | yes | 1136ms |

std::sortdefined in header<algorithm>. Complexity:O(N·log(N)). Here is a specific explanation about standard sorting in C++.

#include<iostream>

#include<vector>

#include<algorithm>

#include<functional>

int main()

{

std::vector<int> values = { 3,5,1,4,2 };

//***********************************************

std::sort(values.begin(), values.end()); // ascending order, sort using the default operator<

for (int value : values)

std::cout << value << ' ';

std::cout << '\n';

//***********************************************

std::sort(values.begin(), values.end(), std::greater<int>()); // descending order, sort using a standard library compare function object

for (int value : values)

std::cout << value << ' ';

std::cout << '\n';

//***********************************************

std::sort(values.begin(), values.end(), [](int a, int b)

{

return a < b;

}); // ascending order, sort using lambda

for (int value : values)

std::cout << value << ' ';

std::cout << '\n';

std::cin.get();

}treat this memory I have as a different type than it actually is.

all we need to do is just get that type as a pointer and cast it to a different pointer and then we can dereference it if we need to

#include<iostream>

struct Entity

{

int x, y;

};

int main()

{

/*int a = 50; // &a, 32 00 00 00

//double value = a; // &value, it is an implicit conversion 00 00 00 00 00 00 49 40

//double value = (double)a; // explicit conversion

//double value = *(double*)&a; // take the integer pointer, and then convert it into double pointer and finnally dereference it to fetch its value. -9.25596e+61, pretty bad, because we take a 4 bytes integer and convert it into 8 bytes double type data. Here, we can watch memory by enter &a and &value, they are located in the same memory block, but because of type difference, we got crashed results.

double& value = *(double*)&a;

value = 0.0;

std::cout << value << std::endl;*/

Entity e = { 5, 8 }; // &e, 05 00 00 00 08 00 00 00

int* position = (int*)&e;// fetch its address and cast is into integer pointer

std::cout << position[0] << ", " << position[1] << std::endl;

std::cin.get();

}The purpose of unions is rather obvious, but for some reason people miss it quite often.

The purpose of union is to save memory by using the same memory region for storing different objects at different times. That's it.

It is like a room in a hotel. Different people live in it for non-overlapping periods of time. These people never meet, and generally don't know anything about each other. By properly managing the time-sharing of the rooms (i.e. by making sure different people don't get assigned to one room at the same time), a relatively small hotel can provide accommodations to a relatively large number of people, which is what hotels are for.

That's exactly what union does. If you know that several objects in your program hold values with non-overlapping value-lifetimes, then you can "merge" these objects into a union and thus save memory. Just like a hotel room has at most one "active" tenant at each moment of time, a union has at most one "active" member at each moment of program time. Only the "active" member can be read. By writing into other member you switch the "active" status to that other member.

For some reason, this original purpose of the union got "overriden" with something completely different: writing one member of a union and then inspecting it through another member. This kind of memory reinterpretation (aka "type punning") is

not a valid use of unions. It generally leads to undefined behavioris decribed as producing implemenation-defined behavior in C89/90.**EDIT: ** Using unions for the purposes of type punning (i.e. writing one member and then reading another) was given a more detailed definition in one of the Technical Corrigendums to C99 standard (see DR#257 and DR#283). However, keep in mind that formally this does not protect you from running into undefined behavior by attempting to read a trap representation.

- union is like class or struct, a union can only have one member

struct Vector2

{

float x, y;

};

struct Vector4

{

union

{

struct

{

float x, y, z, w;

};

struct

{

Vector2 a, b;

};

};

};

void PrintVector2(const Vector2& vector)

{

std::cout << vector.x << ", " << vector.y << std::endl;

}

int main()

{

Vector4 vector = { 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f };

PrintVector2(vector.a);

PrintVector2(vector.b);

vector.z = 500.0f;

std::cout << "-----------" << std::endl;

PrintVector2(vector.a);

PrintVector2(vector.b);

std::cin.get();

}result:

1, 2

3, 4

-----------

1, 2

500, 4- whenever you are writing a class that you will be extending or that might be subclass whenever you're basically permitting a class to be subclass, you need to 100% declare your destructor as virtual.

#include<iostream>

class Base

{

public:

Base() { std::cout << "Base Constructor\n"; }

virtual ~Base() { std::cout << "Base Destructor\n"; }

};

class Derived : public Base

{

public:

Derived() { m_Array = new int[5]; std::cout << "Derived Constructor\n"; }

~Derived() { delete[] m_Array; std::cout << "Derived Destructor\n"; }

private:

int* m_Array;

};

int main()

{

Base* base = new Base();

delete base;

std::cout << "--------------\n";

Derived* derived = new Derived();

delete derived;

std::cout << "--------------\n";

Base* poly = new Derived();

delete poly; // which causes a memory leak, because Derived Destructor is not called, that' s why we need virtual destructor

std::cin.get();

}results (no virtutal) :

Base Constructor

Base Destructor

--------------

Base Constructor

Derived Constructor

Derived Destructor

Base Destructor

--------------

Base Constructor

Derived Constructor

Base Destructorresults (virtutal) :

Base Constructor

Base Destructor

--------------

Base Constructor

Derived Constructor

Derived Destructor

Base Destructor

--------------

Base Constructor

Derived Constructor

Derived Destructor

Base DestructorVirtual destructors are useful when you might potentially delete an instance of a derived class through a pointer to base class:

class Base { // some virtual methods }; class Derived : public Base { ~Derived() { // Do some important cleanup } };Here, you'll notice that I didn't declare Base's destructor to be

virtual. Now, let's have a look at the following snippet:Base *b = new Derived(); // use b delete b; // Here's the problem!Since Base's destructor is not

virtualandbis aBase*pointing to aDerivedobject,delete bhas undefined behaviour:[In

delete b], if the static type of the object to be deleted is different from its dynamic type, the static type shall be a base class of the dynamic type of the object to be deleted and the static type shall have a virtual destructor or the behavior is undefined.In most implementations, the call to the destructor will be resolved like any non-virtual code, meaning that the destructor of the base class will be called but not the one of the derived class, resulting in a resources leak.

To sum up, always make base classes' destructors

virtualwhen they're meant to be manipulated polymorphically.If you want to prevent the deletion of an instance through a base class pointer, you can make the base class destructor protected and nonvirtual; by doing so, the compiler won't let you call

deleteon a base class pointer.You can learn more about virtuality and virtual base class destructor in this article from Herb Sutter.

C++ includes support for two types of time manipulation:

The chrono library, a flexible collection of types that track time with varying degrees of precision (e.g.

std::chrono::time_point).C-style date and time library (e.g.

std::time) std::chrono libraryThe chrono library defines three main types as well as utility functions and common typedefs.

- clocks

- time points

- durations

```c++ #include #include #include

struct Timer { std::chrono::time_pointstd::chrono::steady_clock start, end; std::chrono::duration duration;

Timer()

{

start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

}

~Timer()

{

end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

duration = end - start;

float ms = duration.count() * 1000.0f;

std::cout << "Timer took " << ms << "ms" << std::endl;

}

};

void Function() { Timer timer; for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) //std::cout << "Hello" << std::endl; //42.8024ms std::cout << "Hello\n"; //18.9782ms }

int main() { Function(); /using namespace std::literals::chrono_literals; auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now(); std::this_thread::sleep_for(1s); auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now(); std::chrono::duration duration = end - start; std::cout << duration.count() << std::endl;/ std::cin.get(); }

* It is a smart way to set timer into struct. To start timer, constructor is a good choice and destructor for end timer.

#### multidimensional arrays

```c++

#include<iostream>

int main()

{

int* array = new int[50]; // anchor 3

int** a2d = new int*[50];// anchor2

for (int i = 0; i < 50; i++)

a2d[i] = new int[50]; // anchor1

a2d[0][0] = 0;

a2d[0][1] = 0;

a2d[0][2] = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 50; i++)

delete[] a2d[i]; // release anchor1 memory

delete[] a2d; // release anchor2 memory

int*** a3d = new int**[50];

for (int i = 0; i < 50; i++)

{

a3d[i] = new int*[50];

for (int j = 0; j < 50; j++)

{

int** ptr = a3d[i];

ptr[j] = new int[50];

}

}

std::cin.get();

}

- storing an image in a one-dimensional way is optimal

- anchor 3 : heap allocation, it doesn't matter with this integer, what we've done here is allocating 200 bytes of memory. we could then proceed to use this integer to store floats

- anchor 1 : we essentially allocated 50 arrays and the location of each one of those arrays is stored in this a2d array

- anchor 2 : a buffer of pointer objects, a pointer to a collection of pointers. we got a pointer to an integer pointer. here, also allocate 200 bytes of memory. we have room to store 200 bytes worth of pointers so 50 pointers, we can go through and set each of those pointers to point to an array and that way we actually end up with is 50 arrays

void HelloWorld(int a)

{

std::cout << "Hello World! Value: " << a << std::endl;

}

int main()

{

typedef void(*HelloWorldFunction)(int); // define a type

HelloWorldFunction function = HelloWorld;

function(8);

function(9);

function(6);

}void PrintValue(int value)

{

std::cout << "Value: " << value << std::endl;

}

void ForEach(const std::vector<int>& values, void(*func)(int))

{

for (int value : values)

func(value);

}

int main()

{

std::vector<int> values = { 1, 5, 4, 2, 3 };

ForEach(values, PrintValue);

ForEach(values, [](int value) {std::cout << "Value: " << value << std::endl; }); // lambdas

std::cin.get();

}Lambda expressions: an unnamed function object capable of capturing variables in scope. link

[capture list] (params list) mutable exception-> return type { function body }| 序号 | 格式 |

|---|---|

| 1 | [capture list] (params list) -> return type {function body} |

| 2 | [capture list] (params list) {function body} |

| 3 | [capture list] {function body} |

| 捕获形式 | 说明 |

|---|---|

| [] | 不捕获任何外部变量 |

| [变量名, …] | 默认以值得形式捕获指定的多个外部变量(用逗号分隔),如果引用捕获,需要显示声明(使用&说明符) |

| [this] | 以值的形式捕获this指针 |

| [=] | 以值的形式捕获所有外部变量 |

| [&] | 以引用形式捕获所有外部变量 |

| [=, &x] | 变量x以引用形式捕获,其余变量以传值形式捕获 |

| [&, x] | 变量x以值的形式捕获,其余变量以引用形式捕获 |

#include<iostream>

#include<vector>

#include<algorithm>

#include<functional>

void ForEach(const std::vector<int>& values, const std::function<void(int)>& func)

{

for (int value : values)

func(value);

}

int main()

{

std::vector<int> values = { 1, 5, 4, 2, 3 };

auto it = std::find_if(values.begin(), values.end(), [](int value) {return value > 3; });

std::cout << *it << std::endl;

int a = 5;

auto lambda = [=](int value) {std::cout << "Value: " << a << std::endl; };

ForEach(values, lambda);

std::cin.get();

}It is Cherno's personal opinion. It might be confusing if you wanna distinguish which function belongs to std library. And there is one case that you might name your function similar to std library function name. So, try to use std namespace less, small scope and remember never put namespace into header file because it is tough to debug your code.

#include<iostream>

#include<string>

namespace apple // it needs implicit conversion

{

void print(const std::string& text)

{

std::cout << text << std::endl;

}

}

namespace orrange // if both exist, this one is a better choice

{

void print(const char* text)

{

std::string temp = text;

std::reverse(temp.begin(), temp.end());

std::cout << temp << std::endl;

}

}

using namespace apple;

using namespace orrange;

int main()

{

print("Hello!"); // "Hello" is a const char array, actually not string

std::cin.get();

}Namespaces provide a method for preventing name conflicts in large projects.

Symbols declared inside a namespace block are placed in a named scope that prevents them from being mistaken for identically-named symbols in other scopes.

Multiple namespace blocks with the same name are allowed. All declarations within those blocks are declared in the named scope.

- More examples can be found here.

The class thread represents a single thread of execution. Threads allow multiple functions to execute concurrently.

Threads begin execution immediately upon construction of the associated thread object (pending any OS scheduling delays), starting at the top-level function provided as a constructor argument. The return value of the top-level function is ignored and if it terminates by throwing an exception, std::terminate is called. The top-level function may communicate its return value or an exception to the caller via std::promise or by modifying shared variables (which may require synchronization, see std::mutex and std::atomic)

std::thread objects may also be in the state that does not represent any thread (after default construction, move from, detach, or join), and a thread of execution may be not associated with any thread objects (after detach).

No two std::thread objects may represent the same thread of execution; std::thread is not CopyConstructible or CopyAssignable, although it is MoveConstructible and MoveAssignable. link

#include<iostream>

#include<thread>

static bool s_Finished = false;

void DoWork()

{

using namespace std::literals::chrono_literals;

std::cout << "Started thread id=" << std::this_thread::get_id() << std::endl;

while (!s_Finished) // s_Finished = false, keep running

{

std::cout << "Working...\n";

std::this_thread::sleep_for(1s);

}

}

int main()

{

std::thread worker(DoWork);

std::cin.get(); // block this thread until we press ENTER

s_Finished = true; // change status, stop working

worker.join(); // we don't do cin.get() until that thread has actually finished its execution

std::cout << "Finished." << std::endl;

std::cout << "Started thread id=" << std::this_thread::get_id() << std::endl;

std::cin.get();

}joinwaits for a thread to finish its execution

use auto if the data type is too long

for example,

for (std::vector<std::string>::iterator it = strings.begin();it != strings.end(); it++) vs for (auto it = strings.begin(); it != strings.end(); it++)

For variables, specifies that the type of the variable that is being declared will be automatically deduced from its initializer.

For functions, specifies that the return type is a trailing return type or will be deduced from its return statements (since C++14)

For non-type template parameters, specifies that the type will be deduced from the argument (since C++17). link

when you create a C++ standard array, it provides you a fixed size, pre-defined data type array, that's what we called static.

standard array is stored on the stack, while vector is stored on the heap, because vector is a changeable array, it needs heap allocation

standard array has boundary check for you optionally, it's up to debug or release mode you choose.

int main()

{

std::array<int, 5> data; //&data, it is a class, so we can keep track of its size

// pay attention that this size is not the real memory size it occupies

int arraysize = data.size();

std::cout << arraysize << std::endl;

data[0] = 2;

data[4] = 1;

std::cin.get();

}Here are two awesome answers about this question, I think they are easy-understood.

Local arrays are created on the stack, and have automatic storage duration -- you don't need to manually manage memory, but they get destroyed when the function they're in ends. They necessarily have a fixed size:

int foo[10];Arrays created with operator new[] have dynamic storage duration and are stored on the heap (technically the "free store"). They can have any size, but you need to allocate and free them yourself since they're not part of the stack frame:

int* foo = new int[10]; delete[] foo;

I think the semantics being used in your class are confusing. What's probably meant by 'static' is simply "constant size", and what's probably meant by "dynamic" is "variable size". In that case then, a constant size array might look like this:

int x[10];and a "dynamic" one would just be any kind of structure that allows for the underlying storage to be increased or decreased at runtime. Most of the time, the std::vector class from the C++ standard library will suffice. Use it like this:

std::vector<int> x(10);// this starts with 10 elements, but the vector can be resized.

std::vectorhasoperator[]defined, so you can use it with the same semantics as an array.

simply to say, macro is just to find/replace

#define WAIT std::cin.get()

#define LOG(x) std::cout << x << std::endl;

int main()

{

LOG("hello");

WAIT;

}#define WAIT std::cin.get() it is not suggested to use preprocessor this way, because if the code is in other file, it may be confusing to know what it exactly means.

Visual Studio projects have separate release and debug configurations for your program. You build the debug version for debugging and the release version for the final release distribution.

In debug configuration, your program compiles with full symbolic debug information and no optimization. Optimization complicates debugging, because the relationship between source code and generated instructions is more complex.

The release configuration of your program has no symbolic debug information and is fully optimized. Debug information can be generated in .pdb files, depending on the compiler options that are used. Creating .pdb files can be useful if you later have to debug your release version. link here

Well, it depends on what language you are using, but in general they are 2 separate configurations, each with its own settings. By default, Debug includes debug information in the compiled files (allowing easy debugging) while Release usually has optimizations enabled.

As far as conditional compilation goes, they each define different symbols that can be checked in your program, but they are language-specific macros.

In general, though, you'll use "Debug" when you want your project to be built with the optimiser turned off, and when you want full debugging/symbol information included in your build (in the .PDB file, usually). You'll use "Release" when you want the optimiser turned on, and when you don't want full debugging information included. link here

to be clear, each program/process on our computer has its own stack/heap

each thread will create its own stack when it gets created, whereas the heap is shared amongst all threads

- allocating memory on heap is a bunch of whole thing, whereas allocating memory on the stack is like one CPU instruction

- when to use stack or heap

newis actually call functionmalloc

#include<iostream>

#include<string>

struct Vector3

{

float x, y, z;

Vector3()

: x(10), y(11), z(12) {}

};

int main()

{

{ // stack memory allocation

int value = 5; // &value, Memory address: 0x0093FC38 (9698360), value: 05 00 00 00

int array[5]; // array is actually a pointer, Memory address: 0x0093FC1C (9698332), value: 01 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 05 00 00 00

array[0] = 1;

array[1] = 2;

array[2] = 3;

array[3] = 4;

array[4] = 5;

Vector3 vector; // &vector, Memory address: 0x0093FC08, 00 00 20 41 00 00 30 41 00 00 40 41

} // for stack variable, if variable is outside the current scope, it gets freed

// 00 00 20 41 00 00 30 41 00 00 40 41 cc cc cc cc cc cc cc cc 01 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 05 00 00 00 cc cc cc cc cc cc cc cc 05 00 00 00

// heap memory allocation

int* hvalue = new int;

*hvalue = 5;

int* harray = new int[5]; // 0x00192E40

harray[0] = 1; // 0x0018CB0C

harray[1] = 2;

harray[2] = 3;

harray[3] = 4;

harray[4] = 5;

Vector3* hvector = new Vector3(); // 0x00192274

// manully free heap memory

delete hvalue;

delete[] harray;

delete hvector;

std::cin.get();

}- we can see that stack memory pointer moves from higher address to lower address

- a stack allocation is extremely fast, it's literally like one CPU instruction. All we do is we move the stack pointer and then we return the address of that stack pointer.

- use

newkeyword to allocate heap memory - use

deleteto manually free heap memory - heap memory address grow from lower address to higher address

Here, we have two projects called Game and Enigne. Game is the main project, so we set its Configuration Type as Application (.exe), and Engine as Static library (.lib). That's the only difference.

- include another project's header file

One way is to use relative path, such as#include"../../Engine/src/Engine.h"

The other way is use absolute path. To achieve this, we can make some property change to Microsoft Visual Studio For example, we set Additional Include Directories as $(SolutionDir)Engine\src

Note that: In my implementation, $(SolutionDir) means the directory where solution file (.sln) locates. And the $(SolutionDir) itself has a backslash symbol (\) at the end of path.

Then we can directly use existing absolute path setting as #include"Engine.h"

Now we fix the compilation problem, but now the linking still has some issues. We first build Engine project, it generates Engine.lib file because we already set its property as Static library (.lib). Then we should right click the Game project and add reference into it. Then the error message is gone.

If we clean the solution, and build Game. The result will look like this : first build Engine and then build Game. Because engine is actually required for game to work since we've added it as a reference and since we are linking against it.

template does not exist until we call it

the compiler writes code for you based on the rules that you've given it and based on the usage of that functional class or anything like that

Here is a specific explanation of templates.

- What is the difference between

#include <filename>and#include “filename”?

In practice, the difference is in the location where the preprocessor searches for the included file.

For

#include <filename>the preprocessor searches in an implementation dependent manner, normally in search directories pre-designated by the compiler/IDE. This method is normally used to include standard library header files.For

#include "filename"the preprocessor searches first in the same directory as the file containing the directive, and then follows the search path used for the#include <filename>form. This method is normally used to include programmer-defined header files.A more complete description is available in the GCC documentation on search paths.

In my opinion, dynamic linking means your executable is separated from some .dll (dynamic linking libraries). On the contrary, static linking means when you compile and link your code, some necessary libraries are incorporated into your final executable file, so it doesn't need some extra libraries support since it already includes all necessary stuffs. In other word, because static linking relates with some compilation and linking procedure, it actually has to consider some optimizations so that the final executable will be more efficient.

- Dynamic linking vs Static linking link

The program we write might make use of other programs (which is usually the case), or libraries of programs. These other programs or libraries must be brought together with the program we write in order to execute it.

Linking is the process of bringing external programs together required by the one we write for its successful execution. Static and dynamic linking are two processes of collecting and combining multiple object files in order to create a single executable. Here we will discuss the difference between them. Read full article on static and dynamic linking for more details.

Linking can be performed at both compile time, when the source code is translated into machine code; and load time, when the program is loaded into memory by the loader, and even at run time, by application programs. And, it is performed by programs called linkers. Linkers are also called link editors. Linking is performed as the last step in compiling a program.

After linking, for execution the combined program must be moved into memory. In doing so, there must be addresses assigned to the data and instructions for execution purposes. The above process can be summarized as program life cycle (write -> compile -> link -> load -> execute).

| Static Linking | Dynamic Linking |

|---|---|

| Static linking is the process of copying all library modules used in the program into the final executable image. This is performed by the linker and it is done as the last step of the compilation process. The linker combines library routines with the program code in order to resolve external references, and to generate an executable image suitable for loading into memory. When the program is loaded, the operating system places into memory a single file that contains the executable code and data. This statically linked file includes both the calling program and the called program. | In dynamic linking the names of the external libraries (shared libraries) are placed in the final executable file while the actual linking takes place at run time when both executable file and libraries are placed in the memory. Dynamic linking lets several programs use a single copy of an executable module. |

| Static linking is performed by programs called linkers as the last step in compiling a program. Linkers are also called link editors. | Dynamic linking is performed at run time by the operating system. |

| Statically linked files are significantly larger in size because external programs are built into the executable files. | In dynamic linking only one copy of shared library is kept in memory. This significantly reduces the size of executable programs, thereby saving memory and disk space. |

| In static linking if any of the external programs has changed then they have to be recompiled and re-linked again else the changes won't reflect in existing executable file. | In dynamic linking this is not the case and individual shared modules can be updated and recompiled. This is one of the greatest advantages dynamic linking offers. |

| Statically linked program takes constant load time every time it is loaded into the memory for execution. | In dynamic linking load time might be reduced if the shared library code is already present in memory. |

| Programs that use statically-linked libraries are usually faster than those that use shared libraries. | Programs that use shared libraries are usually slower than those that use statically-linked libraries. |

| In statically-linked programs, all code is contained in a single executable module. Therefore, they never run into compatibility issues. | Dynamically linked programs are dependent on having a compatible library. If a library is changed (for example, a new compiler release may change a library), applications might have to be reworked to be made compatible with the new version of the library. If a library is removed from the system, programs using that library will no longer work. |

-

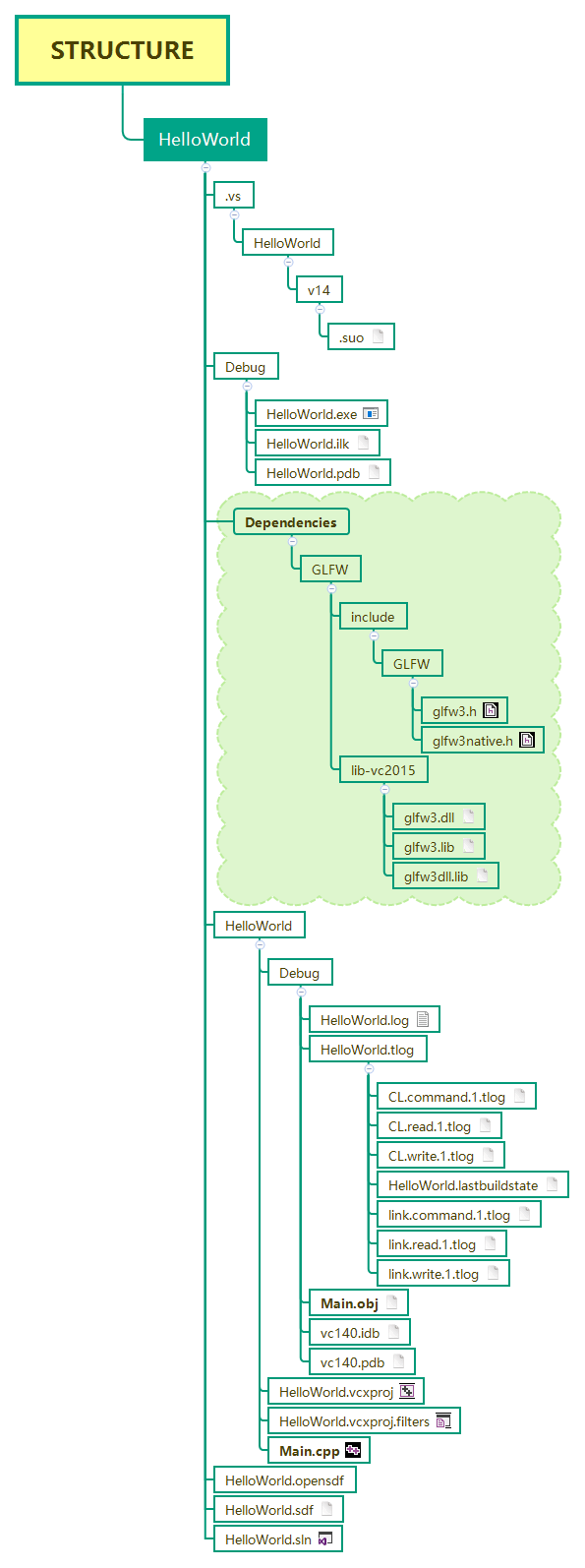

Download GLFW here , choose 32-bit Windows binaries.

-

Unzip glfw-3.2.1.bin.WIN32.zip file

-

Copy include and lib-vc2015 two folders to a new folder called GLFW

-

Copy the entire folder GLFW to a new folder called Dependencies

-

Copy the Dependencies folder to project root directory

-

So, the final project folder looks like this:

- Microsoft Visual Studio Setup

-

Open Project Properties

-

Configuration: All Configurations, Platform: Win32

-

C/C++ -> General -> Additional Include Directories -> $(SolutionDir)Dependencies\GLFW\include

-

Linker -> Input -> Addtional Dependicies -> add "glfw3.lib" into the blank

-

Linker -> General -> Additional Library Directories -> $(SolutionDir)Dependencies\GLFW\lib-vc2015

note that: my $(SolutionDir) is located at D:\c++ files\HelloWorld\

static linking means library actually gets basically put into your excutable so it's just inside your .exe file or whatever your executable is for your operating system.

a dynamic library gets linked at runtime so you still do have some kind of linkage you can choose to load a dynamic library. literally, there is a function called load library which you can use in the Windows API as an example and that will load you like your dynamic library and you can pull function pointers out of that.

glfw3.dll is the runtime kind of dynamic link library that we actually use if we are linking dynamically at runtime

glfw3dll.lib is actually kind of the static library that we use with the dll. This file actually contains all of the locations of the functions and symbols inside glfw3.dll so that we can link against them at compile time

glfw3.lib is the static library, we do not need glfw3.dll file to be without exe file at runtime

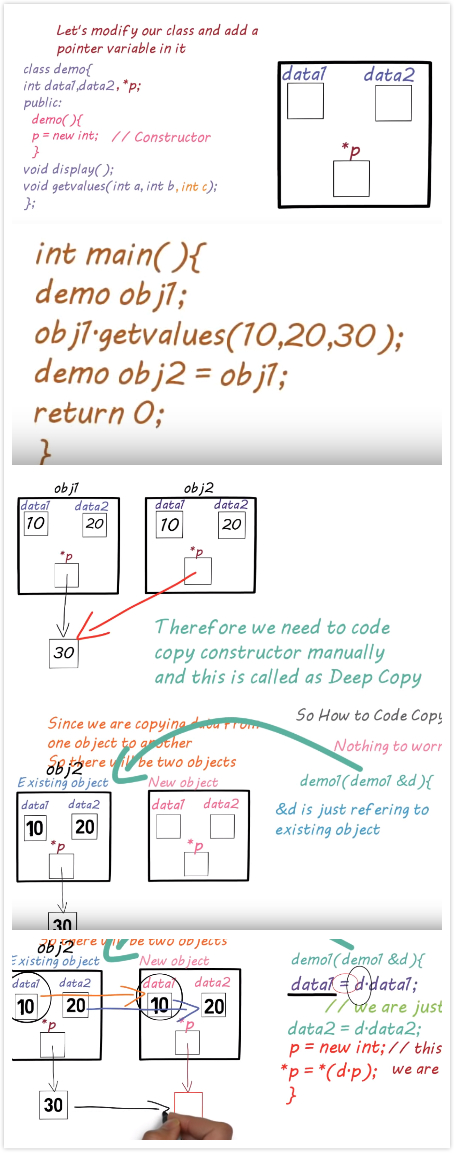

浅拷贝:两个变量进行浅拷贝时,它们指向同一个地址,它们的值相同。这样会有问题,当其中的一个析构了那个地址,另外一个也没有了,有时候会发生错误,但浅拷贝比较廉价。

深拷贝:两个变量进行深拷贝时,第二变量会重新申请一块区域来存放跟第一个变量指向地址的值。两个东西完全是独立的,只是值相同。消耗比较大,因为要重新申请空间。

This is an illustration of how deep copy works I cropped from the video and stitched. The video link is provided above with hyper link. It really helps me a lot.

A shallow copy of an object copies all of the member field values. This works well if the fields are values, but may not be what you want for fields that point to dynamically allocated memory. The pointer will be copied. but the memory it points to will not be copied -- the field in both the original object and the copy will then point to the same dynamically allocated memory, which is not usually what you want. The default copy constructor and assignment operator make shallow copies.

A deep copy copies all fields, and makes copies of dynamically allocated memory pointed to by the fields. To make a deep copy, you must write a copy constructor and overload the assignment operator, otherwise the copy will point to the original, with disasterous consequences.

size_type capacity() const noexcept;Return size of allocated storage capacity

Returns the size of the storage space currently allocated for the vector, expressed in terms of elements.

This capacity is not necessarily equal to the vector size. It can be equal or greater, with the extra space allowing to accommodate for growth without the need to reallocate on each insertion.

Notice that this capacity does not suppose a limit on the size of the vector. When this capacity is exhausted and more is needed, it is automatically expanded by the container (reallocating it storage space). The theoretical limit on the size of a vector is given by member max_size.

The capacity of a vector can be explicitly altered by calling member

vector::reserve.

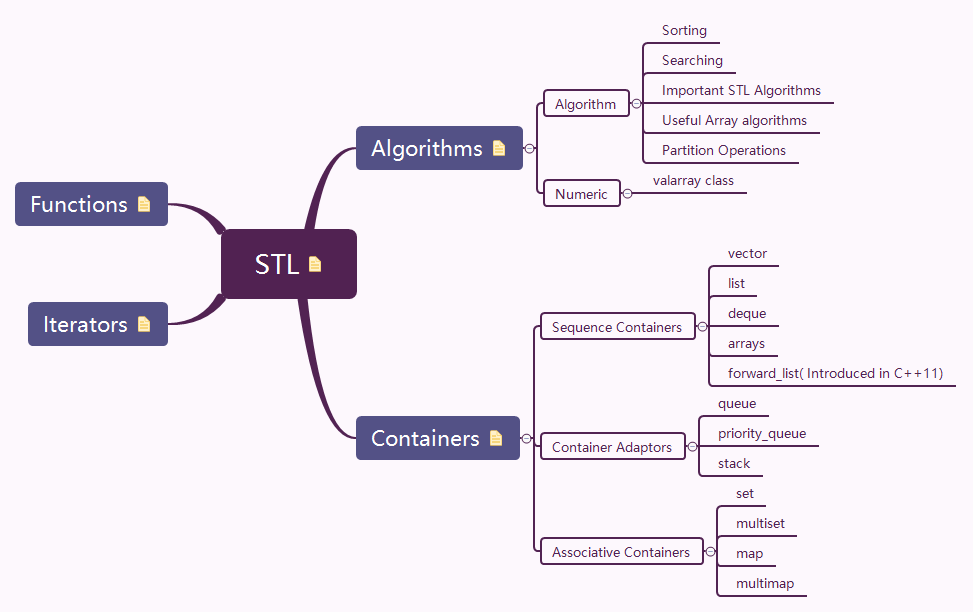

The Standard Template Library (STL) is a set of C++ template classes to provide common programming data structures and functions such as lists, stacks, arrays, etc. It is a library of container classes, algorithms and iterators. It is a generalized library and so, its components are parameterized. A working knowledge of template classes is a prerequisite for working with STL.

- The Standard Template Library (STL) is a set of C++ template classes to provide common programming data structures and functions such as lists, stacks, arrays, etc. It is a library of container classes, algorithms and iterators. It is a generalized library and so, its components are parameterized. A working knowledge of template classes is a prerequisite for working with STL.

- The header algorithm defines a collection of functions especially designed to be used on ranges of elements. They act on containers and provide means for various operations for the contents of the containers.

- Containers or container classes store objects and data. There are in total seven standard “first-class” container classes and three container adaptor classes and only seven header files that provide access to these containers or container adaptors.

- The STL includes classes that overload the function call operator. Instances of such classes are called function objects or functors. Functors allow the working of the associated function to be customized with the help of parameters to be passed.

- As the name suggests, iterators are used for working upon a sequence of values. They are the major feature that allow generality in STL.

Iterators are used to point at the memory addresses of STL containers. They are primarily used in sequence of numbers, characters etc. They reduce the complexity and execution time of program.

Operations of iterators :-

begin():- This function is used to return the beginning position of the container.end():- This function is used to return the after end position of the container.advance():- This function is used to increment the iterator position till the specified number mentioned in its arguments.next():- This function returns the new iterator that the iterator would point after advancing the positions mentioned in its arguments.prev():- This function returns the new iterator that the iterator would point after decrementing the positions mentioned in its arguments.inserter():- This function is used to insert the elements at any position in the container. It accepts 2 arguments, the container and iterator to position where the elements have to be inserted.

#include<iostream>

#include<string>

#include<vector>

struct Vertex

{

float x, y, z;

Vertex(float x, float y, float z)

: x(x), y(y), z(z)

{

}

Vertex(const Vertex& vertex)

: x(vertex.x), y(vertex.y), z(vertex.z)

{

std::cout << "Copied!" << std::endl;

}

};

int main()

{

std::vector<Vertex> vertices;

//std::vector<Vertex> vertices(3); // it's gonna to construct three vertex objects

vertices.reserve(3); // reserve makes sure that we have enough memory

// it prints 6 copies to console.

/*vertices.push_back(Vertex(1, 2, 3 )); // construct it in the current stack frame of the main function and put it into that vector

vertices.push_back(Vertex(4, 5, 6));

vertices.push_back(Vertex(7, 8, 9));*/

vertices.emplace_back(1, 2, 3);

vertices.emplace_back(4, 5, 6);

vertices.emplace_back(7, 8, 9);

std::cin.get();

}optimization 1: construct that vertex in place in the actual memory that the vector actually allocated for us

emplace_back: pass the parameter list for the constructor. hey, construct a vertex object with the following parameters in place in our actual memoryoptimization 2: if you know how many elements you need to add, you can predefine enough size to contain them

reserve

-

Here is a detailed and easy-understood explanation of vector copy constructor.

you cannot copy unique pointer because it's unique.

shared pointer has to allocate another block of memory called the control block where it stores that reference count and if you first create a new entity and then pass it into the shared pointer constructor it has to allocate that's two allocation

when you assign a shared pointer to another shared pointer thus copying it it will increase the ref count but when you assign a shared pointer to a weak pointer, it won't increase the ref count

weak pointer

int main()

{

{

std::weak_ptr<Entity> e0;

{

std::shared_ptr<Entity> sharedEntity = std::make_shared<Entity>();

e0 = sharedEntity;

} // e0 is freed here

}shared pointer

int main()

{

std::shared_ptr<Entity> e0;

{

std::shared_ptr<Entity> sharedEntity = std::make_shared<Entity>();

e0 = sharedEntity;

} // e0 still holds the reference to the entity

} // here, memeory is freed because it passes two scopes*/unique pointer

int main()

{

{

//std::unique_ptr<Entity> entity(new Entity());

std::unique_ptr<Entity> entity = std::make_unique<Entity>();

std::unique_ptr<Entity> e0 = entity; // wrong, because you cannot copy unique pointer

}

} <Entity>is the template argument- entity is the

unique pointername, then we have option to call constructor unique pointeris defined explicitly

what we need is deep copy, copy the entire object

copy constructor is a constructor that gets called for that second string when you actually copy it

when you assign a string to an object that is also a string when you try to create a new variable and you assign it with another variable which has the same type as a variable that you're actually creating you're copying that variable and thus you're calling something called the

copy constructor

#include<iostream>

#include<string>

struct Vector2

{

float x, y;

};

class String // string is made up of an array of characters

{

private:

char* m_Buffer; // point to the buffer of chars

unsigned int m_Size; // keep track of how big the string is

public:

String(const char* string) // constructor

{

m_Size = strlen(string); // calculate how long the string is, so that we can copy the data from the string into the buffer

m_Buffer = new char[m_Size + 1]; // decide how big of the buffer is

memcpy(m_Buffer, string, m_Size);

m_Buffer[m_Size] = 0;

}

String(const String& other) // copy constructor

: m_Size(other.m_Size) // it's just an integer, so shallow copy is okay

{

std::cout << "Copied String!" << std::endl;

m_Buffer = new char[m_Size + 1];

memcpy(m_Buffer, other.m_Buffer, m_Size + 1);

}

/* : m_Buffer(other.m_Buffer), m_Size(other.m_Size) // default copy constructor

{

}*/

// or use another way to define copy constructor

/*String(const String& other)

{

memcpy(this, &other, sizeof(String));

}

*/

~String() // destructor

{

delete[] m_Buffer;

}

char& operator[](unsigned int index) // operator overload

{

return m_Buffer[index];

}

friend std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& stream, const String& string);

};

std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& stream, const String& string)

{

stream << string.m_Buffer;

return stream;

}

// if reference is not used, we get three string copies happening

// anchor3, anchor4, anchor5 totally three times copying

// what's actually happening is every time we copy a string we allocate memory on the heap, copy all that memory and then at the end of it, we free it. That's completely unnecessary.

void PrintString(const String& string) // anchor2

{

std::cout << string << std::endl;

}

int main()

{

/*int a = 2;

int b = a;

b = 3; // a remains 2

*/

/*Vector2 a = { 2, 3 };

Vector2 b = a;

b.x = 5; // a, b are two separate Vector2s

*/

/*Vector2* a = new Vector2();

Vector2* b = a; // actually copy the pointer

b->x = 2; // a and b are both pointing to the same memory address

*/

String string = "Cherno"; // m_Buffer = 0x00a517d0

String second = string; // anchor3, shallow cpoy a string, m_Buffer = 0x00a517d0

// these two char pointers point to the same address

second[2] = 'a';

PrintString(string); // anchor4

PrintString(second); // anchor5

/*std::cout << string << std::endl;

std::cout << second << std::endl;

*/

std::cin.get();

} // anchor 1, when the code run to anchor1, it tries to delete the buffer twice so we are trying to free the same block of memory twice. that's why we get a crash because the memory has already been freed it's not ours, we can not free it againstrcpyincludes the null termination character- keep in mind that always pass your objects by const reference

const& - In this code, a string class is created, which includes two members:

char pointer andint. - In user-defined string class,

constructor,destructor,copy constructor,operator overloadingand afrienddeclaration are developed. frienddeclaration is a new feature for me, the detailed knowledge can be found here.

The

frienddeclaration appears in a class body and grants a function or another class access to private and protected members of the class where the friend declaration appears.

It's to access a member function or member variable of an object through a pointer, as opposed to a regular variable or reference.

For example: with a regular variable or reference, you use the

.operator to access member functions or member variables.std::string s = "abc"; std::cout << s.length() << std::endl;But if you're working with a pointer, you need to use the

->operator:std::string* s = new std::string("abc"); std::cout << s->length() << std::endl;It can also be overloaded to perform a specific function for a certain object type. Smart pointers like

shared_ptrandunique_ptr, as well as STL container iterators, overload this operator to mimic native pointer semantics.For example:

std::map<int, int>::iterator it = mymap.begin(), end = mymap.end(); for (; it != end; ++it) std::cout << it->first << std::endl;

a->bmeans(*a).b.If

ais a pointer,a->bis the memberbof whichapoints to.

- get the offset of a certain member variable in memory

struct Vector3

{

float x, y, z;

};

int main() // entry point

{

int offset = (int)&((Vector3*)nullptr)->z;

std::cout << offset << std::endl;

std::cin.get();

}int offset = (int)&((Vector3*)nullptr)->z;

- first, we cast a

nullptrtoVector3*type - use

->to point to the class member - use

&to obtain the address of variable in the memory - use

intto cast it into integer type

It's called a vector because Alex Stepanov, the designer of the Standard Template Library, was looking for a name to distinguish it from built-in arrays. He admits now that he made a mistake, because mathematics already uses the term 'vector' for a fixed-length sequence of numbers. Now C++0X will compound this mistake by introducing a class 'array' that will behave similar to a mathematical vector.

Alex's lesson: be very careful every time you name something.

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/581426/why-is-a-c-vector-called-a-vector

vector belongs to std namespace

in fact, it shouldn't be called vector, it should be called something like arraylist

vector can actually resize, thus it is truely called dynamic array

all u need to do is allocate a vector, such as 10 elements, when you wanna extend it much bigger, then it will create a new array, copy the old one and paste it to the new one, finally, automatically delete the old one.

operators are just functions

#include<iostream>

#include<string>

struct Vector2 // public is default

{

float x, y;

Vector2(float x, float y)

: x(x), y(y) {}

Vector2 Add(const Vector2& other) const // not modify class members

{

return Vector2(x + other.x, y + other.y); // other means struct parameters (x, y), use point to specify the point it refers to

}

Vector2 operator+(const Vector2& other) const

{

return Add(other);

}

Vector2 Multiply(const Vector2& other) const

{

return Vector2(x * other.x, y * other.y);

}

Vector2 operator*(const Vector2& other) const

{

return Multiply(other);

}

bool operator==(const Vector2& other) const

{

return x == other.x && y == other.y;

}

bool operator!=(const Vector2& other) const

{

//return !operator==(other);

return !(*this == other);

}

};

std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& stream, const Vector2& other)

{

stream << other.x << ", " << other.y;

return stream;

}

int main()

{

Vector2 position(4.0f, 4.0f);

Vector2 speed(0.5f, 1.5f);

Vector2 powerup(1.1f, 1.1f);

Vector2 result1 = position.Add(speed.Multiply(powerup));

Vector2 result2 = position + speed * powerup;

std::cout << result1 << std::endl;

std::cout << result2 << std::endl;

if (result1 == result2)

{

}

std::cin.get();

}- print class-inner content to the console

std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& stream, const Vector2& other)

{

stream << other.x << ", " << other.y;

return stream;

}- use c++

overloadfeature std::ostreamis the original definition of<<operator<<to indicate it's gonna use to overfload operatorstd::ostream& streamis the left side of<<const Vector2& otheris the right side of<<needed to be print out

- Error: no operator "<<" matches these operands

std::cout << result1 << std::endl;

std::cout << result2 << std::endl; - left side of

<<is a classcout - right side of

<<is various data types thatcoutalready knows how to print out - operand types are

std::ostream << Vector2 - we can't do this because there is no

overloadfor this operator which takes in an output stream which is whatcoutis and then an actualVector2but we can add that

Besides, here is a detailed explanation of C++ Overloading (Operator and Function)

C++ allows you to specify more than one definition for a function name or an operator in the same scope, which is called function overloading and operator overloading respectively.

An overloaded declaration is a declaration that is declared with the same name as a previously declared declaration in the same scope, except that both declarations have different arguments and obviously different definition (implementation).

When you call an overloaded function or operator, the compiler determines the most appropriate definition to use, by comparing the argument types you have used to call the function or operator with the parameter types specified in the definitions. The process of selecting the most appropriate overloaded function or operator is called overload resolution.

Function Overloading

You can have multiple definitions for the same function name in the same scope. The definition of the function must differ from each other by the types and/or the number of arguments in the argument list. You cannot overload function declarations that differ only by return type.

Operators Overloading

You can redefine or overload most of the built-in operators available in C++. Thus, a programmer can use operators with user-defined types as well.

Overloaded operators are functions with special names: the keyword "operator" followed by the symbol for the operator being defined. Like any other function, an overloaded operator has a return type and a parameter list.

Box operator+(const Box&);declares the addition operator that can be used to add two Box objects and returns final Box object. Most overloaded operators may be defined as ordinary non-member functions or as class member functions. In case we define above function as non-member function of a class then we would have to pass two arguments for each operand as follows :

Box operator+(const Box&, const Box&);

- Video

thisis only accessible to us through amember function,member functionmeaning a function that belongs to aclassso amethodand inside amethodwe can referencethisand whatthisis is apointerto the currentobject instancethat themethodbelongs towe first need to

instantiateanobjectand then call themethodso themethodhas to be called with a validobjectand thethiskeyword is apointerto that object

class Entity

{

public:

int x, y;

Entity(int x, int y)

{

this->x = x;

this->y = y;

}

int GetX() const // we are not allowed to modify the class

{

const Entity* e = this; // so this has to be const type

return x;

}

};

int main()

{

Entity e;

std::cin.get();

}Every object in C++ has access to its own address through an important pointer called this pointer. The this pointer is an implicit parameter to all member functions. Therefore, inside a member function, this may be used to refer to the invoking object.

Friend functions do not have a this pointer, because friends are not members of a class. Only member functions have a this pointer.

**Why does C++ have both pointers and references? **

C++ inherited pointers from C, so they couldn’t be removed without causing serious compatibility problems. References are useful for several things, but the direct reason they were introduced in C++ was to support operator overloading. For example:

void f1(const complex* x, const complex* y) // without references { complex z = *x+*y; // ugly // ... } void f2(const complex& x, const complex& y) // with references { complex z = x+y; // better // ... }When should I use references, and when should I use pointers?

Use references when you can, and pointers when you have to.

Should I use call-by-value or call-by-reference?

That depends on what you are trying to achieve:

If you want to change the object passed, call by reference or use a pointer;

e.g.,

void f(X&);orvoid f(X*);.If you don’t want to change the object passed and it is big, call by const reference;

e.g.,

void f(const X&);.Otherwise, call by value;

e.g.

void f(X);.What does “big” mean? Anything larger than a couple of words.

The

&character in C++ is dual purpose. It can mean (at least)

- Take the address of a value

- Declare a reference to a type

The use you're referring to in the function signature is an instance of #2. The parameter

string& stris a reference to astringinstance. This is not just limited to function signatures, it can occur in method bodies as well.

In this video, two kinds of object lifetime are introduced, they are stack lifetime and scope lifetime.

- stack lifetime

#include<iostream>

#include<string>

class Entity

{

public:

Entity()

{

std::cout << "Created Entity!" << std::endl;

}

~Entity()

{

std::cout << "Destroyed Entity!" << std::endl;

}

};

int* CreateArray()

{

int array[50]; // declare it on the stack

return array; // it returns a pointer to that stack memory, the stack memory gets cleared as soon as we go out of scope

}

int main()

{

int* a = CreateArray();

{

Entity* e = new Entity(); // set breakpoint, even run pass anchor1 to anchor2

} // anchor1

std::cin.get(); // anchor2

}- the stack-based variable gets destroyed as soon as we go out of the scope

- it is a mistake that people will create a stack-based variable and try to return a pointer to it, not realizing that once that function ends and you go out of scope that variables done

- scope lifetime

#include<iostream>

#include<string>

class Entity

{

public:

Entity()

{

std::cout << "Created Entity!" << std::endl;

}

~Entity()

{

std::cout << "Destroyed Entity!" << std::endl;

}

};

class ScopedPtr

{

private:

Entity* m_Ptr;

public:

ScopedPtr(Entity* ptr)

: m_Ptr(ptr)

{

}

~ScopedPtr()

{

delete m_Ptr;

}

};

int main()

{

{

ScopedPtr e = new Entity();

}

std::cin.get();

}the scoped pointer class itself the scoped pointer object gets allocated on the stack which means it gets deleted and when it gets deleted automatically equals delete in the destructor which deletes that pointer m_Ptr that it's wrapping

Some good references can be found as follows:

- C++ Classes and Objects

- Object

- Object (computer science)

- Lifetime

- What is the lifecycle of a C++ object?

- What are all the ways to create a C++ object?

Same as C: they can be global variables, local automatic, local static or dynamic. You may be confused by the constructor, but simply think that every time you create an object, a constructor is called. Always. Which constructor is simply a matter of what parameters are used when creating the object.

Assignment does not create a new object, it simply copies from one oject to another, (think of

memcpybut smarter).

- What are all the different initialization syntaxes associated with all these types of object creation? What's the difference between T f = x, T f(x);, T f{x};, etc.?

T f(x)is the classic way, it simply creates an object of typeTusing the constructor that takesxas argument.T f{x}is the new C++11 unified syntax, as it can be used to initialize aggregate types (arrays and such), but other than that it is equivalent to the former.T f = xit depends on whetherxis of typeT. If it is, then it equivalent to the former, but if it is of different type, then it is equivalent toT f = T(x). Not that it really matters, because the compiler is allowed to optimize away the extra copy (copy elision).T(x). You forgot this one. A temporary object of typeTis created (using the same constructor as above), it is used whereever it happens in the code, and at the end of the current full expression, it is destroyed.T f. This creates a value of typeTusing the default constructor, if available. That is simply a constructor that takes no parameters.T f{}. Default contructed, but with the new unified syntax. Note thatT f()is not an object of typeT, but instead a function returningT!.T(). A temporary object using the default constructor.

- Most importantly, when is it correct to copy/assign/whatever = is in C++, and when do you want to use pointers?

You can use the same as in C. Think of the copy/assignment as if it where a

memcpy. You can also pass references around, but you also may wait a while until you feel comfortable with those. What you should do, is: do not use pointers as auxiliary local variables, use references instead.

- Finally, what are all these things like shared_ptr, weak_ptr, etc.?

They are tools in your C++ tool belt. You will have to learn through experience and some mistakes...

shared_ptruse when the ownership of the object is shared.unique_ptruse when the ownership of the object is unique and unambiguous.weak_ptrused to break loops in trees ofshared_ptr. They are not detected automatically.vector. Don't forget this one! Use it to create dynamic arrays of anything.PS: You forgot to ask about destructors. IMO, destructors are what gives C++ its personality, so be sure to use a lot of them!

we basically have two choices here and the difference between the choices is where the memory comes from which memory were actually going to be creating our object in when we create an object in C++, it needs to occupy some memory even if we write a class that is completely empty, no class members or nothing like that it has to occupy at least one byte of memory stack objects for example, their lifetime is actually controlled by the scope that they declared and as soon as that variable goes out of scope, that's it the memory is free because when that scope ends the stack pops and anything that scope frame in that stack frame that gets freed once you allocated an object in that heap, it's up to you to determine when to free that block of memory

- create class

class Entity

{

private:

String m_Name;

public:

Entity()

: m_Name("Unkown") //constructor

{

}

Entity(const String& name)

: m_Name(name)

{

}

const String& GetName() const

{

return m_Name;

}

};- objects created on the stack

int main()

{

Entity* e;

{ // use curly brace to create a scope

Entity entity("Cherno");

e = &entity; // when the code runs to the next line of anchor1, content of e is freed because of scope

std::cout << entity.GetName() << std::endl;

} // anchor1

std::cin.get();

}- objects created on the heap

int main()

{

Entity* e;

{ // use curly brace to create a scope

Entity* entity = new Entity("Cherno");

e = entity; // when the code runs to the next line of anchor2, content of e is freed because of heap memory is freed

std::cout << entity->GetName() << std::endl;

} // anchor1

std::cin.get();

delete e; // anchor2

}-

Entity* entity = new Entity("Cherno");we allocate memory on theheap, call theconstructorand this newentityactually returns an entity pointer it returns the location on theheapwhere this entity has actually been allocated -

std::cout << entity->GetName() << std::endl;sinceentityis aEntity pointer, you should dereference first,(*entity).GetName()

The main purpose of

newis to allocate memory on theheapspeciallyThe

newexpression attempts to allocate storage and then attempts to construct and initialize either a single unnamed object, or an unnamed array of objects in the allocated storage. The new-expression returns a prvalue pointer to the constructed object or, if an array of objects was constructed, a pointer to the initial element of the array. link

int a = 2;

int* b = new int[50]; // remember new returns a pointer, 200bytes

Entity* e = new Entity(); // not only allocate the memory, but alse calls the constructor, kind of like (Entity*)malloc(sizeof(Entity) in C, but the latter one does not call the constructor

delete e; // free() in C, but delete also calls the destructor

delete[] b; // when free the array memory created by new square brackets

std::cin.get();- first case

X x;

Y y(x) //explicit conversion- second case

X x;

Y y = x; //implicit conversionone uses a Y's constructor and one uses the assignment operator though.

Nope. In the second case it's not an assignment, it's an initialization, the assignment operator (

operator=) is never called; instead, a non-explicitone-parameter constructor (that accepts the type X as a parameter) is called.