diff --git a/GROSSARY.md b/GROSSARY.md

index 877bf7e..57a21f6 100644

--- a/GROSSARY.md

+++ b/GROSSARY.md

@@ -5,13 +5,17 @@

| abstract syntax tree | 抽象構文木 |

| concrete syntax tree | 解析木 |

| context | コンテキスト(証明やプログラム中のスコープを指す場合)、文脈(それ以外) |

+| delaboration | デラボレーション |

| elaborate | 精緻化 |

| elaboration | エラボレーション |

+| elaborator | エラボレータ |

| hypothesis | 仮定 |

| expression | 式 |

| implication | 含意 |

| metavariable | メタ変数 |

| notation | 記法 |

+| parse | パース |

| reflection | リフレクション |

| syntax | 構文 |

-| term | 項 |

+| term | 項(式を構成する要素)、用語 |

+| unification | ユニフィケーション |

diff --git a/lean/main/02_overview.lean b/lean/main/02_overview.lean

index 1c0bdbd..59a6cb9 100644

--- a/lean/main/02_overview.lean

+++ b/lean/main/02_overview.lean

@@ -1,104 +1,255 @@

/-

+--#--

# Overview

+--#--

+# 概要

+

+--#--

In this chapter, we will provide an overview of the primary steps involved in the Lean compilation process, including parsing, elaboration, and evaluation. As alluded to in the introduction, metaprogramming in Lean involves plunging into the heart of this process. We will explore the fundamental objects involved, `Expr` and `Syntax`, learn what they signify, and discover how one can be turned into another (and back!).

+--#--

+この章では、パース・エラボレーション・評価など、Leanのコンパイルプロセスに関わる主なステップの概要を説明します。導入で言及したように、Leanのメタプログラミングはこのプロセスの核心に踏み込むことになります。まず基本的なオブジェクトである `Expr` と `Syntax` を探求し、それらが何を意味するかを学び、片方をもう一方に(そして反対方向に!)どのように変えることができるかを明らかにします。

+

+--#--

In the next chapters, you will learn the particulars. As you read on, you might want to return to this chapter occasionally to remind yourself of how it all fits together.

+--#--

+次の章では、その詳細を学びます。本書を読み進めながら、時々この章に立ち返り、すべてがどのように組み合わさっているかを思い出すとよいでしょう。

+

+--#--

## Connection to compilers

+--#--

+## コンパイラにアクセスする

+

+--#--

Metaprogramming in Lean is deeply connected to the compilation steps - parsing, syntactic analysis, transformation, and code generation.

+--#--

+Leanでのメタプログラミングは、パース、構文解析、変換、コード生成といったコンパイルのステップと深く関連しています。

+

+--#--

> Lean 4 is a reimplementation of the Lean theorem prover in Lean itself. The new compiler produces C code, and users can now implement efficient proof automation in Lean, compile it into efficient C code, and load it as a plugin. In Lean 4, users can access all internal data structures used to implement Lean by merely importing the Lean package.

+--#--

+> Lean4はLeanの定理証明器をLean自体で再実装したものです。新しいコンパイラはCコードを生成し、ユーザはLeanで効率的な証明自動化を実装し、それを効率的なCコードにコンパイルしてプラグインとしてロードすることができます。Lean4では、Leanパッケージをインポートするだけで、Leanの実装に使用されるすべての内部データ構造にアクセスできます。

>

> Leonardo de Moura, Sebastian Ullrich ([The Lean 4 Theorem Prover and Programming Language](https://pp.ipd.kit.edu/uploads/publikationen/demoura21lean4.pdf))

+--#--

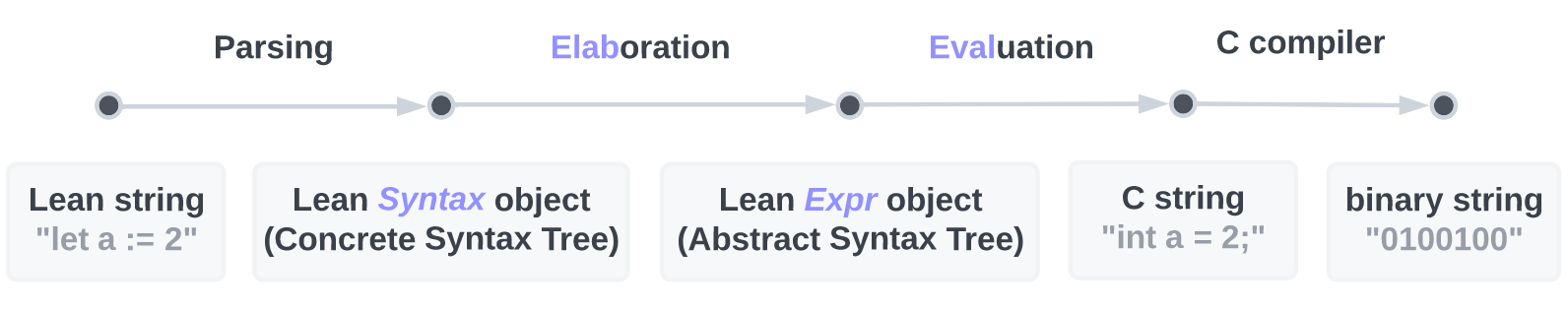

The Lean compilation process can be summed up in the following diagram:

+--#--

+Leanのコンパイルプロセスは以下の図にまとめることができます:

+

-First, we will start with Lean code as a string. Then we'll see it become a `Syntax` object, and then an `Expr` object. Then finally we can execute it.

+--#--

+First, we will start with Lean code as a string. Then we'll see it become a `Syntax` object, and then an `Expr` object. Then finally we can execute it.

+

+--#--

+まず、Leanのコード自体である文字列から始まります。それから `Syntax` オブジェクトになり、次に `Expr` オブジェクトになります。最終的にそれを実行します。

+--#--

So, the compiler sees a string of Lean code, say `"let a := 2"`, and the following process unfolds:

-1. **apply a relevant syntax rule** (`"let a := 2"` ➤ `Syntax`)

+--#--

+そのため、コンパイラはLeanのコード文字列、例えば `"let a := 2"` を見て次のような処理を展開します:

+--#--

+1. **apply a relevant syntax rule** (`"let a := 2"` ➤ `Syntax`)

+

+--#--

+1. **関連する構文ルールの適用** (`"let a := 2"` ➤ `Syntax`)

+

+--#--

During the parsing step, Lean tries to match a string of Lean code to one of the declared **syntax rules** in order to turn that string into a `Syntax` object. **Syntax rules** are basically glorified regular expressions - when you write a Lean string that matches a certain **syntax rule**'s regex, that rule will be used to handle subsequent steps.

-2. **apply all macros in a loop** (`Syntax` ➤ `Syntax`)

+--#--

+ 構文解析のステップにおいて、Leanはコードの文字列を宣言された **構文ルール** (syntax rules)のどれかにマッチさせ、その文字列を `Syntax` オブジェクトにしようとします。**構文ルール** と聞くと仰々しいですが基本的には正規表現です。ある **構文ルール** の正規表現にマッチするLean文字列を書くと、そのルールは後続のステップの処理に使用されます。

+

+--#--

+2. **apply all macros in a loop** (`Syntax` ➤ `Syntax`)

+

+--#--

+2. **すべてのマクロの繰り返し適用** (`Syntax` ➤ `Syntax`)

+--#--

During the elaboration step, each **macro** simply turns the existing `Syntax` object into some new `Syntax` object. Then, the new `Syntax` is processed similarly (repeating steps 1 and 2), until there are no more **macros** to apply.

-3. **apply a single elab** (`Syntax` ➤ `Expr`)

+--#--

+ エラボレーションのステップでは、各 **マクロ** (macro)は既存の `Syntax` オブジェクトを新しい `Syntax` オブジェクトに単純に変換します。そして新しい `Syntax` は適用する **マクロ** が無くなるまで同じように処理が行われます(ステップ1と2を繰り返します)。

+--#--

+3. **apply a single elab** (`Syntax` ➤ `Expr`)

+

+--#--

+3. **elabの単発適用** (`Syntax` ➤ `Expr`)

+

+--#--

Finally, it's time to infuse your syntax with meaning - Lean finds an **elab** that's matched to the appropriate **syntax rule** by the `name` argument (**syntax rules**, **macros** and **elabs** all have this argument, and they must match). The newfound **elab** returns a particular `Expr` object.

This completes the elaboration step.

+--#--

+ いよいよ構文に意味を吹き込む時です。Leanは `name` 引数によって適切な **構文ルール** にマッチする **elab** を見つけます(**構文ルール** と **マクロ**、**elabs** はすべてこの引数を持っており、必ずマッチしなければなりません)。新しく見つかった **elab** は特定の `Expr` オブジェクトを返します。これでエラボレーションのステップは完了です。

+

+--#--

The expression (`Expr`) is then converted into executable code during the evaluation step - we don't have to specify that in any way, the Lean compiler will handle doing so for us.

+--#--

+この式(`Expr`)は評価ステップにおいて実行可能なコードに変換されます。このステップはLeanのコンパイラがよしなに処理してくれるため、指定をする必要はありません。

+

+--#--

## Elaboration and delaboration

+--#--

+## エラボレーションとデラボレーション

+

+--#--

Elaboration is an overloaded term in Lean. For example, you might encounter the following usage of the word "elaboration", wherein the intention is *"taking a partially-specified expression and inferring what is left implicit"*:

+--#--

+エラボレーション(elaboration)はLeanにおいて多重な意味を持つ用語です。例えば、「エラボレーション」という言葉について、**「部分的に指定された式を受け取り、暗黙にされたものを推測する」** を意図した次のような用法に出会うことでしょう:

+

+--#--

> When you enter an expression like `λ x y z, f (x + y) z` for Lean to process, you are leaving information implicit. For example, the types of `x`, `y`, and `z` have to be inferred from the context, the notation `+` may be overloaded, and there may be implicit arguments to `f` that need to be filled in as well.

>

> The process of *taking a partially-specified expression and inferring what is left implicit* is known as **elaboration**. Lean's **elaboration** algorithm is powerful, but at the same time, subtle and complex. Working in a system of dependent type theory requires knowing what sorts of information the **elaborator** can reliably infer, as well as knowing how to respond to error messages that are raised when the elaborator fails. To that end, it is helpful to have a general idea of how Lean's **elaborator** works.

>

-> When Lean is parsing an expression, it first enters a preprocessing phase. First, Lean inserts "holes" for implicit arguments. If term t has type `Π {x : A}, P x`, then t is replaced by `@t _` everywhere. Then, the holes — either the ones inserted in the previous step or the ones explicitly written by the user — in a term are instantiated by metavariables `?M1`, `?M2`, `?M3`, .... Each overloaded notation is associated with a list of choices, that is, the possible interpretations. Similarly, Lean tries to detect the points where a coercion may need to be inserted in an application `s t`, to make the inferred type of t match the argument type of `s`. These become choice points too. If one possible outcome of the elaboration procedure is that no coercion is needed, then one of the choices on the list is the identity.

+> When Lean is parsing an expression, it first enters a preprocessing phase. First, Lean inserts "holes" for implicit arguments. If term t has type `Π {x : A}, P x`, then t is replaced by `@t _` everywhere. Then, the holes — either the ones inserted in the previous step or the ones explicitly written by the user — in a term are instantiated by metavariables `?M1`, `?M2`, `?M3`, .... Each overloaded notation is associated with a list of choices, that is, the possible interpretations. Similarly, Lean tries to detect the points where a coercion may need to be inserted in an application `s t`, to make the inferred type of t match the argument type of `s`. These become choice points too. If one possible outcome of the elaboration procedure is that no coercion is needed, then one of the choices on the list is the identity.

+

+--#--

+> Leanが処理するために `λ x y z, f (x + y) z` のような式を入力する場合、あなたは情報を暗黙的なものとしています。例えば、`x`・`y`・`z` の型は文脈から推測しなければならず、`+` という表記はオーバーロードされたものかもしれず、そして `f` に対して暗黙的に埋めなければならない引数があるかもしれません。

+>

+> この **「部分的に指定された式を受け取り、暗黙にされたものを推測する」** プロセスは **エラボレーション** (elaboration)として知られています。Leanの **エラボレーション** アルゴリズムは強力ですが、同時に捉えがたく複雑です。依存型理論のシステムで作業するには、**エラボレータ** (elaborator)がどのような種類の情報を確実に推論できるかということを知っておくことに加え、エラボレータが失敗した時に出力されるエラーメッセージへの対応方法を知っておくことが必要です。そのためには、Leanの **エラボレータ** がどのように動作するかということへの一般的な考え方を知っておくと便利です。

+>

+> Leanが式をパースするとき、まず前処理フェーズに入ります。最初に、Leanは暗黙の引数のための「穴」(hole)を挿入します。項tが `Π {x : A}, P x` という方を持つ場合、tは利用箇所すべてで `@t _` に置き換えられます。次に穴(前のステップで挿入されたもの、またはユーザが明示的に記述したもの)はメタ変数 `?M1`・`?M2`・`?M3`・... によってインスタンス化されます。オーバーロードされた各記法は選択肢のリスト、つまり取りうる解釈に関連付けられています。同様に、Leanは適用 `s t` に対して、推論されるtの型を `s` の引数の型と一致させるために型の強制を挿入する必要がある箇所を検出しようとします。これらも選択するポイントになります。あるエラボレーションの結果、型の強制が不要になる可能性がある場合、リスト上の選択肢の1つが恒等になります。

>

> ([Theorem Proving in Lean 2](http://leanprover.github.io/tutorial/08_Building_Theories_and_Proofs.html))

+--#--

We, on the other hand, just defined elaboration as the process of turning `Syntax` objects into `Expr` objects.

+--#--

+一方で、本書では `Syntax` オブジェクトを `Expr` オブジェクトに変換するプロセスとしてエラボレーションを定義しました。

+

+--#--

These definitions are not mutually exclusive - elaboration is, indeed, the transformation of `Syntax` into `Expr`s - it's just so that for this transformation to happen we need a lot of trickery - we need to infer implicit arguments, instantiate metavariables, perform unification, resolve identifiers, etc. etc. - and these actions can be referred to as "elaboration" on their own; similarly to how "checking if you turned off the lights in your apartment" (metavariable instantiation) can be referred to as "going to school" (elaboration).

+--#--

+これらの定義は相互に排他的なものではありません。エラボレーションとは、確かに `Syntax` から `Expr` への変換のことですが、ただこの変換を行うためには、暗黙の引数を推論したり、メタ変数をインスタンス化したり、ユニフィケーションを行ったり、識別子を解決したりなどなど、多くの技法が必要になります。そしてこれらのアクション自体もエラボレーションそのものとして言及されます;これは「部屋の電気を消したかどうかをチェックする」(メタ変数のインスタンス化)を「学校に行く」(エラボレーション)と呼ぶことができるのと同じです。

+

+--#--

There also exists a process opposite to elaboration in Lean - it's called, appropriately enough, delaboration. During delaboration, an `Expr` is turned into a `Syntax` object; and then the formatter turns it into a `Format` object, which can be displayed in Lean's infoview. Every time you log something to the screen, or see some output upon hovering over `#check`, it's the work of the delaborator.

+--#--

+Leanにはエラボレーションと反対のプロセスも存在し、これは名実ともにデラボレーション(delaboration)と呼ばれます。デラボレーションにおいては、`Expr` が `Syntax` オブジェクトに変換されます;そしてフォーマッタがそれを `Format` オブジェクトに変換し、これがLeanのinfoviewに表示されます。画面に何かログが表示されたり、`#check` にカーソルを合わせて出力が表示されたりするのはすべてデラボレータ(delaborator)の仕事です。

+

+--#--

Throughout this book you will see references to the elaborator; and in the "Extra: Pretty Printing" chapter you can read about delaborators.

+--#--

+本書全体を通して、エラボレータについての言及を目にすることでしょう;そして「付録:整形した出力」章では、デラボレータについて読むことができます。

+

+--#--

## 3 essential commands and their syntax sugars

+--#--

+## 3つの必須コマンドとその糖衣構文

+

+--#--

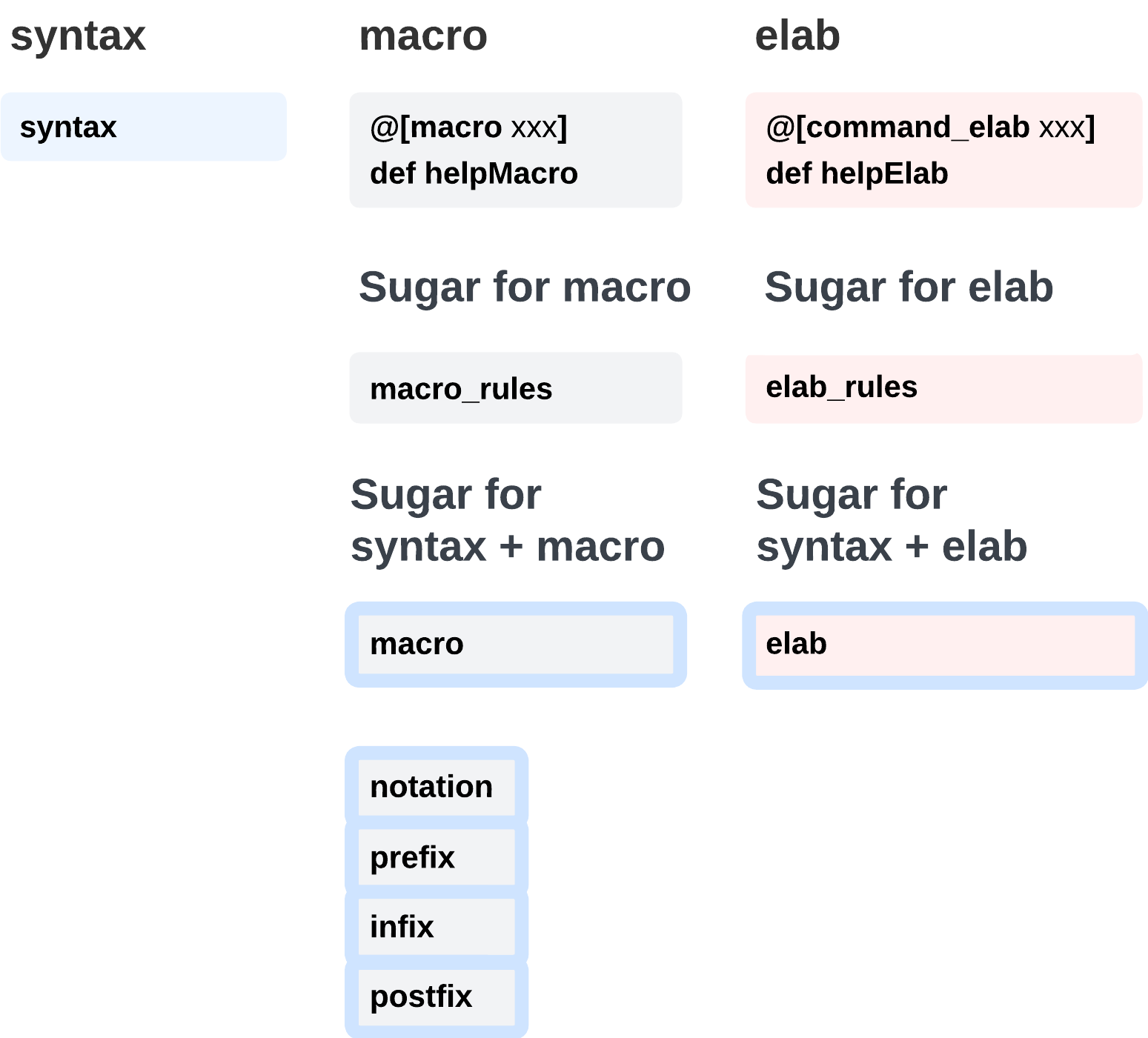

Now, when you're reading Lean source code, you will see 11(+?) commands specifying the **parsing**/**elaboration**/**evaluation** process:

+--#--

+さて、Leanのソースコードを呼んでいると、 **パース**/**エラボレーション**/**評価** のプロセスを指定するための11(+?)種のコマンドを見るでしょう:

+

+--#--

In the image above, you see `notation`, `prefix`, `infix`, and `postfix` - all of these are combinations of `syntax` and `@[macro xxx] def ourMacro`, just like `macro`. These commands differ from `macro` in that you can only define syntax of a particular form with them.

+--#--

+上記の画像では `notation`・`prefix`・`infix`・`postfix` がありますが、これらはすべて `macro` と同じように `syntax` と `@[macro xxx] def ourMacro` を組み合わせたものです。これらのコマンドは `macro` と異なり、特定の形式の構文のみを定義することができます。

+

+--#--

All of these commands are used in Lean and Mathlib source code extensively, so it's well worth memorizing them. Most of them are syntax sugars, however, and you can understand their behaviour by studying the behaviour of the following 3 low-level commands: `syntax` (a **syntax rule**), `@[macro xxx] def ourMacro` (a **macro**), and `@[command_elab xxx] def ourElab` (an **elab**).

+--#--

+これらのコマンドはすべてLean自体やMathlibのソースコードで多用されるため覚えておく価値は十分にあります。しかし、これらのほとんどは糖衣構文であり、以下の3つの低レベルコマンドの動作を学んでおくことでその動作を理解することができます:`syntax` (**構文ルール**)・`@[macro xxx] def ourMacro` (**マクロ**)・`@[command_elab xxx] def ourElab` (**elab**)。

+

+--#--

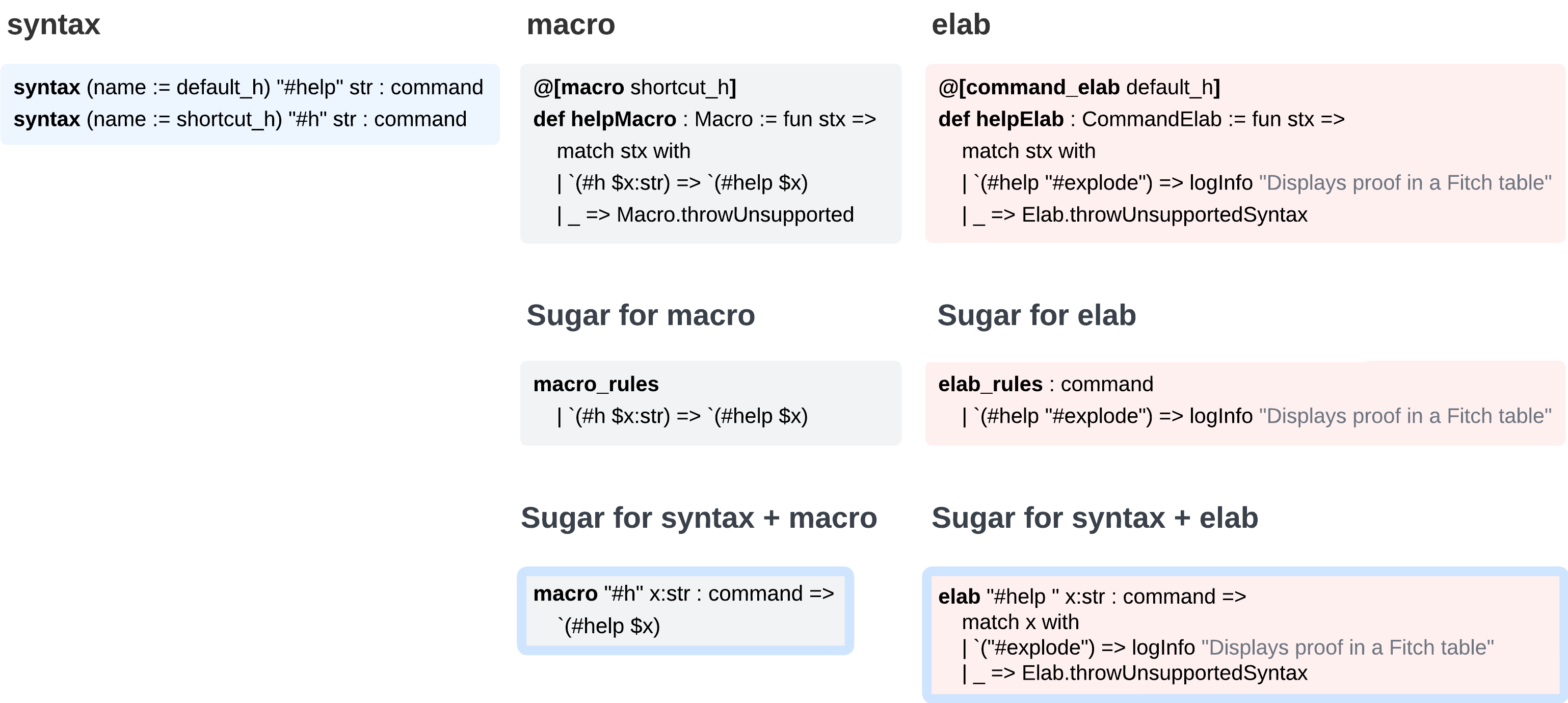

To give a more concrete example, imagine we're implementing a `#help` command, that can also be written as `#h`. Then we can write our **syntax rule**, **macro**, and **elab** as follows:

+--#--

+より具体的な例として、`#help` コマンドを実装しようとしているとします。そうすると、**構文ルール**・**マクロ**・**elab** を次のように書くことができます:

+

+--#--

This image is not supposed to be read row by row - it's perfectly fine to use `macro_rules` together with `elab`. Suppose, however, that we used the 3 low-level commands to specify our `#help` command (the first row). After we've done this, we can write `#help "#explode"` or `#h "#explode"`, both of which will output a rather parsimonious documentation for the `#explode` command - *"Displays proof in a Fitch table"*.

-If we write `#h "#explode"`, Lean will travel the `syntax (name := shortcut_h)` ➤ `@[macro shortcut_h] def helpMacro` ➤ `syntax (name := default_h)` ➤ `@[command_elab default_h] def helpElab` route.

+--#--

+この図は一行ずつ読むことを想定していません。`macro_rules` と `elab` を併用しても何ら問題ありません。しかし、3つの低レベルコマンドを使って `#help` コマンド(最初の行)を指定したとしましょう。これによって、`#help "#explode"` もしくは `#h "#explode"` と書くことができます。どちらのコマンドも `#explode` コマンドのかなり簡素なドキュメントとして *"Displays proof in a Fitch table"* を出力します。

+

+--#--

+If we write `#h "#explode"`, Lean will travel the `syntax (name := shortcut_h)` ➤ `@[macro shortcut_h] def helpMacro` ➤ `syntax (name := default_h)` ➤ `@[command_elab default_h] def helpElab` route.

If we write `#help "#explode"`, Lean will travel the `syntax (name := default_h)` ➤ `@[command_elab default_h] def helpElab` route.

+--#--

+もし `#h "#explode"` と書くと、Leanは `syntax (name := shortcut_h)` ➤ `@[macro shortcut_h] def helpMacro` ➤ `syntax (name := default_h)` ➤ `@[command_elab default_h] def helpElab` というルートをたどります。もし `#help "#explode"` と書くと、Leanは `syntax (name := default_h)` ➤ `@[command_elab default_h] def helpElab` というルートをたどります。

+

+--#--

Note how the matching between **syntax rules**, **macros**, and **elabs** is done via the `name` argument. If we used `macro_rules` or other syntax sugars, Lean would figure out the appropriate `name` arguments on its own.

-If we were defining something other than a command, instead of `: command` we could write `: term`, or `: tactic`, or any other syntax category.

-The elab function can also be of different types - the `CommandElab` we used to implement `#help` - but also `TermElab` and `Tactic`:

+--#--

+**構文ルール**・**マクロ**・**elab** のマッチングは `name` 引数を介して行われることに注意してください。もし `macro_rules` や他の糖衣構文を使った場合、Leanは自力で適切な `name` 引数を見つけるでしょう。

+

+--#--

+If we were defining something other than a command, instead of `: command` we could write `: term`, or `: tactic`, or any other syntax category.

+The elab function can also be of different types - the `CommandElab` we used to implement `#help` - but also `TermElab` and `Tactic`:

-- `TermElab` stands for **Syntax → Option Expr → TermElabM Expr**, so the elab function is expected to return the **Expr** object.

-- `CommandElab` stands for **Syntax → CommandElabM Unit**, so it shouldn't return anything.

-- `Tactic` stands for **Syntax → TacticM Unit**, so it shouldn't return anything either.

+--#--

+コマンド以外のものを定義する場合、`: command` の代わりに `: term` や `: tactic` などの構文カテゴリを書くことができます。elab関数は `#help` の実装に使用した `CommandElab` だけでなく `TermElab` と `Tactic` など、さまざまな型を使用することができます:

+--#--

+- `TermElab` stands for **Syntax → Option Expr → TermElabM Expr**, so the elab function is expected to return the **Expr** object.

+- `CommandElab` stands for **Syntax → CommandElabM Unit**, so it shouldn't return anything.

+- `Tactic` stands for **Syntax → TacticM Unit**, so it shouldn't return anything either.

+

+--#--

+- `TermElab` は **Syntax → Option Expr → TermElabM Expr** の省略形で、elab関数は **Expr** オブジェクトを返すことが期待されます。

+- `CommandElab` は **Syntax → CommandElabM Unit** の省略形で、何も返さないべきです。

+- `Tactic` は **Syntax → TacticM Unit** の省略形で、何も返さないべきです。

+

+--#--

This corresponds to our intuitive understanding of terms, commands and tactics in Lean - terms return a particular value upon execution, commands modify the environment or print something out, and tactics modify the proof state.

+--#--

+これはLeanの項・コマンド・タクティクに対する直観的な理解に対応しています。項は実行時に特定の値を返し、コマンドは環境を変更したり何かを出力したりし、タクティクは証明の状態を変更します。

+

+--#--

## Order of execution: syntax rule, macro, elab

+--#--

+## 実行順序:構文ルール・マクロ・elab

+

+--#--

We have hinted at the flow of execution of these three essential commands here and there, however let's lay it out explicitly. The order of execution follows the following pseudocodey template: `syntax (macro; syntax)* elab`.

-Consider the following example.

+--#--

+これら3つの重要なコマンドの実行の流れについては、これまであちこちで匂わせてきましたが、ここで明確にしましょう。実行順序は次のような疑似的なテンプレートに従います:`syntax (macro; syntax)* elab` 。

+--#--

+Consider the following example.

+--#--

+以下の例を考えてみましょう。

-/

import Lean

open Lean Elab Command

@@ -122,47 +273,110 @@ red -- finally, blue!

/-

+--#--

The process is as follows:

-- match appropriate `syntax` rule (happens to have `name := xxx`) ➤

+--#--

+この処理は以下のように動きます:

+

+--#--

+- match appropriate `syntax` rule (happens to have `name := xxx`) ➤

apply `@[macro xxx]` ➤

-- match appropriate `syntax` rule (happens to have `name := yyy`) ➤

+--#--

+- 適切な `syntax` ルールにマッチ(ここでは `name := xxx`)➤ `@[macro xxx]` を適用 ➤

+

+--#--

+- match appropriate `syntax` rule (happens to have `name := yyy`) ➤

apply `@[macro yyy]` ➤

-- match appropriate `syntax` rule (happens to have `name := zzz`) ➤

- can't find any macros with name `zzz` to apply,

+--#--

+- 適切な `syntax` ルールにマッチ(ここでは `name := yyy`)➤ `@[macro yyy]` を適用 ➤

+

+--#--

+- match appropriate `syntax` rule (happens to have `name := zzz`) ➤

+ can't find any macros with name `zzz` to apply,

so apply `@[command_elab zzz]`. 🎉.

+--#--

+- 適切な `syntax` ルールにマッチ(ここでは `name := zzz`)➤ `zzz` に適用されるマクロが見つからず、したがって `@[command_elab zzz]` を適用します。🎉。

+

+--#--

The behaviour of syntax sugars (`elab`, `macro`, etc.) can be understood from these first principles.

+--#--

+糖衣構文(`elab` や `macro` 等)の挙動はこれらの第一原理から理解することができます。

+

+--#--

## Manual conversions between `Syntax`/`Expr`/executable-code

+--#--

+## `Syntax`/`Expr`/実行コード間の手動変換

+

+--#--

Lean will execute the aforementioned **parsing**/**elaboration**/**evaluation** steps for you automatically if you use `syntax`, `macro` and `elab` commands, however, when you're writing your tactics, you will also frequently need to perform these transitions manually. You can use the following functions for that:

+--#--

+Leanでは `syntax`・`macro`・`elab` を使うことで前述の **パース**/**エラボレーション**/**評価** のステップを自動的に実行してくれますが、しかしタクティクを書く際にはこれらの変換を頻繁に手動で行う必要が出るでしょう。この場合、以下の関数を使うことができます:

+

+--#--

Note how all functions that let us turn `Syntax` into `Expr` start with "elab", short for "elaboration"; and all functions that let us turn `Expr` (or `Syntax`) into `actual code` start with "eval", short for "evaluation".

+--#--

+`Syntax` を `Expr` に変換する関数はすべて「elaboration」の略である「elab」で始まることに注意してください;また、`Expr` (もしくは `Syntax`)を実際のコードに変換する関数はすべて「evaluation」の略である「eval」から始まります。

+

+--#--

## Assigning meaning: macro VS elaboration?

-In principle, you can do with a `macro` (almost?) anything you can do with the `elab` function. Just write what you would have in the body of your `elab` as a syntax within `macro`. However, the rule of thumb here is to only use `macro`s when the conversion is simple and truly feels elementary to the point of aliasing. As Henrik Böving puts it: "as soon as types or control flow is involved a macro is probably not reasonable anymore" ([Zulip thread](https://leanprover.zulipchat.com/#narrow/stream/270676-lean4/topic/The.20line.20between.20term.20elaboration.20and.20macro/near/280951290)).

+--#--

+## 代入の意味:マクロ vs エラボレーション?

+--#--

+In principle, you can do with a `macro` (almost?) anything you can do with the `elab` function. Just write what you would have in the body of your `elab` as a syntax within `macro`. However, the rule of thumb here is to only use `macro`s when the conversion is simple and truly feels elementary to the point of aliasing. As Henrik Böving puts it: "as soon as types or control flow is involved a macro is probably not reasonable anymore" ([Zulip thread](https://leanprover.zulipchat.com/#narrow/stream/270676-lean4/topic/The.20line.20between.20term.20elaboration.20and.20macro/near/280951290)).

+

+--#--

+原則として、`elab` 関数でできることは(ほとんど?)すべて `macro` でできます。ただ単に `elab` の本体にあるものを `macro` の中に構文として書くだけで良いです。ただし、この経験則を使うのは `macro` 使う方が変換が単純でエイリアスの設定が本当に初歩的であるときだけにすべきです。Henrik Böving に曰く:「型や制御フローが絡んでしまうとマクロはもはや妥当ではないでしょう」 ([Zulip thread](https://leanprover.zulipchat.com/#narrow/stream/270676-lean4/topic/The.20line.20between.20term.20elaboration.20and.20macro/near/280951290))。

+

+--#--

So - use `macro`s for creating syntax sugars, notations, and shortcuts, and prefer `elab`s for writing out code with some programming logic, even if it's potentially implementable in a `macro`.

+--#--

+従って、糖衣構文・記法・ショートカットを作るには `macro` を使い、プログラミングのロジックを含むコードを書き出す場合には、たとえ `macro` で実装できうるものだとしても `elab` を使いましょう。

+

+--#--

## Additional comments

+--#--

+## 追加のコメント

+

+--#--

Finally - some notes that should clarify a few things as you read the coming chapters.

+--#--

+最後に、これからの章を読むにあたって、いくつかの事柄を明らかにしておきましょう。

+

+--#--

### Printing Messages

+--#--

+### メッセージの表示

+

+--#--

In the `#assertType` example, we used `logInfo` to make our command print

something. If, instead, we just want to perform a quick debug, we can use

`dbg_trace`.

+--#--

+`#assertType` の例ではコマンドに何かしら表示させるために `logInfo` を使いました。これの代わりにデバッグを素早く行いたい場合は `dbg_trace` を使うことができます。

+

+--#--

They behave a bit differently though, as we can see below:

+--#--

+しかし、以下に見るように両者の振る舞いは少し異なります:

-/

elab "traces" : tactic => do

@@ -177,8 +391,13 @@ example : True := by -- `example` is underlined in blue, outputting:

trivial

/-

+--#--

### Type correctness

+--#--

+### 型の正しさ

+

+--#--

Since the objects defined in the meta-level are not the ones we're most

interested in proving theorems about, it can sometimes be overly tedious to

prove that they are type correct. For example, we don't care about proving that

@@ -187,4 +406,6 @@ use the `partial` keyword if we're convinced that our function terminates. In

the worst-case scenario, our function gets stuck in a loop, causing the Lean server to crash

in VSCode, but the soundness of the underlying type theory implemented in the kernel

isn't affected.

--/

\ No newline at end of file

+--#--

+メタレベルで定義されるオブジェクトは定理証明において最も興味があるものではないため、型が正しいことを証明するのは時として退屈になりすぎることがあります。例えば、ある式をたどる再帰関数がwell-foundedであることの証明に関心はありません。そのため、関数が終了すると確信が持てるのなら `partial` キーワードを使うことができます。最悪のケースでは関数がループにはまり、Leanサーバがvscodeでクラッシュしてしまいますが、カーネルに実装されている基本的な型理論の健全性は影響を受けません。

+-/

diff --git a/md/SUMMARY.md b/md/SUMMARY.md

index 2191d4b..d31c72d 100644

--- a/md/SUMMARY.md

+++ b/md/SUMMARY.md

@@ -5,7 +5,7 @@

# 本文

- [はじめに](./main/01_intro.md)

-- [Overview](./main/02_overview.md)

+- [概要](./main/02_overview.md)

- [Expressions](./main/03_expressions.md)

- [MetaM](./main/04_metam.md)

- [Syntax](./main/05_syntax.md)