Design files for Reaper's costume from Overwatch

This repo is my first for an actual "product" I've designed. It's a step forward in my exploration of embedded systems and circuit design, expanding on both my previous Light Sensor and STM32F407 Familiarization projects.

This project came about due to a need from a friend of some electronics and 3D models for a custom costume she was making: Reaper, from the videogame Overwatch.

Specifically, Reaper's dual shotguns. The requirements were:

- All the red lights on the guns (two spots underneath the barrel, one on the side-switch, one on the front underneath the barrels, and one near the top of the gun facing backwards towards Reaper) need to be illuminated with a lighting effect accurate to the in-game look.

- The barrels need to illuminate when the trigger is pulled, to mimic shots being fired.

- Sound effects of a shot firing need to play every time the trigger is pulled, with no more than 4 shots per gun firing before the "reload" sound effect is played. Both guns need to reload at the same time, so if one is empty before the other, it needs to wait for the last shot to be fired from the other gun. Additionally, voice lines Reaper says in the video game after a kill need to play during the reload... making sure to play a different voice line each time.

- Power is to be provided by two AA batteries per gun, due to space constraints in the handle.

So... Logically, thinking about this, I know I need some lights, a speaker, a radio, a microcontroller fast enough to handle the task of producing sound somehow, and a circuit board to hold everything together.

Cool! Sounds like a fun project. Let's start by figuring out what kind of lighting looks good.

LEDs are an obvious first thought, since they're so cheap and ubiquitous. But they're also very bright, and has a point-like look, even when diffused. Even after throwing everything I could think of at a standard 5mm red LED, I just couldn't get it to achieve the same look as the game. I tried thinking of other things that might produce a much deeper, richer red... A while ago, I had seen something cool on Adafruit called EL Wire, that might work. It's got a really, really nice effect:

But it requires a clunky inverter, and I'm dubious about how it'll show up in bright light.

I started looking around for other solutions, and stumbled upon this:

"Side-glow Fiber Optic Cable." It looks great, and it's not electrical in nature! You can cut it to length, and whatever color LED you put into it is what you'll get out. So I ordered some, to try it out with the red LED. Unfortunately, it just wasn't bright enough. Too much light was being emitted from the sides of the LED, and not enough was going directly into the fiber optic cable. I was certain that if I could just get the LED to focus all of its energy into it, it would be bright enough. The first thing that comes to mind when trying to get light into a single point is a laser, so I started researching red laser diode modules and how to use them.

Turns out, all they need is 3 volts and a constant current supply of around 20 milliamps, and you can get 10 for $6.00 on Amazon (with Prime, even!).

I ordered some, and I was blown away at how great it looked with the fiber optic cable!

My phone's camera doesn't do it justice. To the human eye, the light is perceived as very intense red. Not blindingly so, but it definitely looks a whole lot like what the video game shows for the lighting effects! I guess we're using lasers in our project.

A side-note about these laser modules: They're supposed to be supplied with an active constant-current power supply, but I found that a 22Ω resistor was plenty sufficient for stabilizing the current. These are for lighting effects, not scientific measurement.

My next step was to rip an existing solid 3D gun model off of thingiverse and hollow it out to find space for all the parts, and also figure out how to get the trigger to move instead of just being static like on the original model.

After much work figuring out how to make everything fit, and mount securely inside, I came up with this configuration:

In the handle are the two AA batteries, and behind the trigger is the microswitch I'm using to detect actuation and also provide the necessary "springiness" to give the feeling of a nice click when depressed. In blue is the speaker, positioned on a sliding tray above the decorative vent holes I drilled out to pass sound through to the outside world. Towards the front of the gun is the circuit board I still had yet to design, but I made it plenty big enough (8cm x 10cm) so that I should have no trouble fitting all the components I need onto it. On the circuit board, I modeled a little laser-holder to keep the side-glow fiber optic cable attached to the lasers, and the lasers attached to the board. Just a couple 3mm screw holes holding a couple clamshells together, with enough tension to make sure nothing moves. Simple, and easy to 3D print.

Speaking of circuit boards, I need to design one! But I need to figure out what to put on it first... I've got the lasers' chunk of real-estate dished out, but I still need to determine exactly what else I need to provision for. Well, I need a microcontroller to start. I think the ol' PIC10F220's out of the question for this one... I need something with a little more oomph. I remember really liking the STM32F407 when I was screwing around with my dev board, but that's probably a bit overkill for a project like this. I want a Goldilocks processor... so in the spirit of trying to use the bare minimum in my projects, and because I used a PIC in my last project, I'm going to look for a bottom-of-the-barrel STM32. Let's see what eBay's got.

I mean... that's nice and all, but that's still a lot of pins at a very high clock speed. I said bottom-of-the-barrel, darn it!

Now we're talking! It's not even in a quad flat package, it's dual-inline with only 20 pins! Let's load up CubeMX and see what it's got for features. (probably not a whole lot)

Actually, not bad! It's got an ADC, support for both I2C and SPI, 5 general-purpose timers plus a watchdog timer, and a real-time clock. Not bad for a 20-pin part. I think we have a winner for our microcontroller.

Also, as a bonus, dev boards are dirt-cheap.

Alright, I think now's a good time to tackle the hard part: sound.

I know that I use file formats like WAV and MP3 to store sound on my PC, but is any of that readable to a microcontroller of this simplicity? I needed to learn a lot more about how these formats work under the hood, and how other people have gone about playing sound on devices like the Arduino.

Apparently, since a WAV file is uncompressed, it represents what is called "PCM Audio", or "Pulse-Code Modulation Audio". This means that the bytes in a WAV file sequentially represent amplitude data of the audio waveform - the thing you see when you open something in Audacity or the like. Depending on the sample rate and resolution, this can be as simple as one byte representing an aplitude of anywhere from 0 to 255, played one after the other, 8000 times per second for an 8-bit, 8kHz audio file.

Here's a good visualization:

Each line is 1/8000 of a second apart (sample rate of 8kHz) and the value at each line can be anywhere from 0 to 255 (8-bit resolution). Turn those numbers into voltages that move a speaker cone, and baby, you've got audio.

Now how the heck do I get this thing to talk to a speaker? It certainly doesn't do so natively, like the STM32F407 does... gotta figure that one out on my own. Somehow, I need to get that waveform out to an amplifier. Most times, that's done with something called a Digital to Analog converter, or DAC, which you'll hear thrown around on various products' descriptions. But in the spirit of bare-minimum, I tried to see if I could use Pulse-Width Modulation combined with a filtering circuit to create the analog waves.

I'm just going to say right now, that I couldn't get that to work no matter how hard I tried. I'm going to have to bookmark that technique for later. For now, I'm saying "screw it" and using a DAC. But which DAC should I use?

A fairly popular one amongst the hobbyist community, produced in droves in China, is called the MCP4725.

It's a nifty little thing, in the same size package as the the PIC10F220 I'm so familiar with. 12-Bit Resolution, rail-to-rail output which means it'll give me the full swing of 0v to 3.3v, and it supports High-Speed I2C which is more than enough to cover the 8kHz sample rate plus I2C frame data. Perfect! Now I gotta find an amplifier, because I really don't trust this thing to drive a speaker the size of what I need.

Now, every good EE has heard of the legendary LM386. Since 1969, it's been powering hobbyist and professional audio projects where "sounds good enough" reigns supreme. It's simple, yet versatile, and does what it's supposed to without a whole lot else. It takes an input, makes it louder, and gives you an output for an 8Ω speaker. If you need it even louder, put a capacitor between pins 1 and 8. Sound too staticy? Put a capacitor between pin 7 and ground. Boom, done. Loud. Happy? Good.

These chips are so common, even the knockoffs have knockoffs. You can buy buckets of them for next to nothing, which makes them great for this project and possibly future ones since I'll probably have plenty laying around.

One problem, though... It needs a minimum of 4v to work, and everything else I've got is 3.3v. Looks like I need two power rails... remember that, for later.

Wait, sorry, I see two problems... the LM386 input is expecting a voltage between 0 and 0.4v, not 0 and 3.3v like my DAC is putting out. Anything above 0.4v is going to get clipped, which means I need to figure out how to scale the audio. I want to make use of the full 12-bit resolution of the MCP4725, so I'm thinking maybe scaling the output of the DAC using some analog circuitry before it gets to the LM386 might be a good idea.

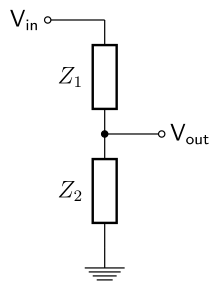

A common tactic for scaling an analog signal like this is to use two resistors in a configuration called a "voltage divider".

If we want 3.3v (the upper limit of the DAC) to correspond with 0.4v (the upper limit of the amplifier input), and we start with a known resistor value of 150kΩ for Z1 (because that's a standard resistor value that I know is produced), we get a nominal Z2 value of 20.69kΩ, which is not a standard resistor that is produced. Luckily, 20kΩ is, and that's "close enough for government work."

I'd also like to explain why I'm choosing resistors in this range of values... the answer, is because I just need a voltage reference for the LM386. I don't want to waste unnecessary battery power heating up resistors, but I also don't want so much resistance that the voltage reference isn't responsive enough for my purposes. These are in a sweet spot between both.

So after all of my dev boards arrived in the mail, and I pulled an LM386 out of an old door alarm, I ended up building this:

The STM32 communicates over High-Speed I2C to the MCP4725, which outputs the PCM WAV file to voltages anywhere between 0 to 3.3v depending on the wave amplitude at that "frame" of the sound file. That 0 to 3.3v signal gets coupled to the voltage divider in the reverse-"L" shape by a 10nF capacitor to help smooth out the "jumps" in the 8kHz audio, then finally gets sent to the LM386 input pin. The LM386 output pin gets coupled to the 8Ω speaker by a pretty big capacitor. Here, I'm using a 330µF electrolytic to remove the DC bias from the amplifier, so the speaker cone goes through its whole range of motion. Additionally, I put a high-pass filter on the output pin to chop off some unwanted low-frequency noise.

The sound file itself is stored on the STM32, compiled from a C character array that I just iterate through 8000 times per second in a for loop.

Unfortunately, due to how small the storage on-board the STM32 is, I found only one voice line of Reaper's that was short enough to fit on it! In order to store all of them, I'm going to need some external storage.

I thought to myself... "Hm... flash storage has been getting pretty dense and cheap, lately. I wonder what kind of chips are out there that might store the amount of data I'm looking for."

I looked into Micro SD Cards, but even for a 2GB card it took over 100 milliamps! Holy cow, I don't have that kind of overhead with these two AA batteries! And 2GB is way overkill for what I need. I had to find something smaller, and lower-power.

Eventually, my friend ended up finding this:

The Macronix MX25L1606EM2I, a 2MB SPI flash chip capable of exchanging data at very high speeds, at very low power. The cool thing about SPI flash chips is that their form factor is pretty much standardized, as well as their pinout and (for the most part) their instruction set... so in the future, if I theoretically wanted to switch out this chip for a larger one, or a different manufacturer, it should be a drop-in replacement. Pretty convenient!

But unlike a Micro SD Card, I can't just plop this into my PC and drag files onto it... This is just bare memory, I needed to be able to talk to it somehow.

Looking around on eBay, I found a pretty highly-rated Flash IC programmer that supported both SPI and I2C chips called the CH341A.

The MX25L1606EM2I can't plug directly into the ZFI socket on the programmer, so I made sure to find one that included this little "clamp" to hold onto the 8 pins of the flash chip.

The software for it looks like this:

And I gotta say, after changing the language from Chinese, it was pretty much plug-and-play. (With the exception of the diagram in the lower left being WRONG! The chip should be rotated 180 degrees, in that same 8-pin slot.) The programmer talked to the chip just fine, and I could key-in values at whatever memory addresses I wanted.

So... I got the chip to talk to my computer, and store data successfully. But how about reading it from the microcontroller?

Reading into the datasheet, the command structure for reading from the chip is:

- Pull the Chip-Select pin low.

- Send it

0x03in the first byte of data. This is to instruct the chip that we intend to read from it, and we are about to give it an address in the next 3 frames. - Send it the first byte of the 6-byte address.

- Send it the second byte of the 6-byte address.

- Send it the third byte of the 6-byte address. Note: after these are all sent, the chip will start reading off not only that byte, but every consecutive byte until it reaches the end.

- Finally tell it to shut up by pulling the Chip-Select pin high.

And that, in theory, should work. There's two other pins on the chip that are of interest: Write-Protect, and Hold. Write-Protect does what you'd expect, and Hold stops the entire chip from doing anything. From my adventures diving into EE forums, I learned that those pins aren't necessary for normal operation, and can just be left unconnected.

But... when I tried reading a memory address on the flash chip from the STM32, it wouldn't respond! I was getting no data back at all!

So, to troubleshoot, I hooked the chip back up to the CH341A, but this time using DuPont jumper wires, and verified that it could talk to the PC. Then, I pulled the Write-Protect jumper out to see if that was the culprit... No dice, the flash chip was still acting normally. Next, I pulled the Hold jumper out... and bingo! I got a Read Error from the software saying that the chip wasn't responding.

So, instead of leaving Hold unconnected like I originally did, I tried tying it to ground with that jumper... And the read error went away! It was behaving normally again.

On the microcontroller side of things, I tried using another jumper to tie Hold to ground while leaving Write-Protect floating... and suddenly, I got the byte of data I was expecting!

My breadboard prototype now looked like this:

After uploading a larger WAV file to the flash chip than would fit on the STM32, I tried reading each byte and outputting it to the DAC fast enough to play the voice line. The result was actually pretty promising, and sounded decent considering the mediocre speaker I was using.

Next challenge: the radio.

So, after a cursory glance at what other people are using for their low-cost RF needs for Arduino projects and whatnot, I was consistently pointed towards the nRF24L01 module.

These are about a buck a pop on Amazon, with Prime shipping included. Interestingly enough, these also communicate over SPI... which means I now have to make sure that the MX25L1606EM2I and nRF24L01 will play nice together on the same line. After all, with the Hold pin needing to be tied to ground, which it shouldn't have to be, it very well may not.

See... SPI isn't addressed. You have to expressly tell each chip, "HEY! I'm talking to you." And sometimes, when finished talking to that chip, it won't release the MISO line like it's supposed to, which prevents other chips from talking.

SD Cards are apparently notorious for exhibiting that behavior when operating in SPI mode, so... yeah, I'm glad I didn't use one on this project.

A common workaround for this is to put a device called a "tri-state buffer" on the problem device, which then forcefully disengages the MISO line for that device when the Chip-Select line goes high, thus allowing other devices to talk.

So the only way to figure out if the MX25L1606EM2I was a problem device, was to try it on the same SPI line as the nRF24L01.

I tacked on a radio module to my breadboard, and whipped up a little battery-powered stand-alone nRF24L01 + STM32 project.

Then, I wrote some code that did the following:

- Battery-powered module transmits to waiting sound-breadboard module that it should start playing the soundbyte from the flash chip, which is indicated by the blue LED on the sound-breadboard module turning on.

- The sound-breadboard module instantly transmits back to the battery-powered module to turn on its LED, indicating that bidirectional communication is possible.

- After the soundbyte finishes playing on the sound-breadboard, it instructs the battery-powered module to turn off its LED. This indicates a successful handover from radio, to flash chip, to radio... I.E. both devices are capable of releasing the MISO line without issue.

- Once the battery-powered module has turned off its LED, it instantly instructs the sound-breadboard module to do the same.

The result of these four transactions should yield two devices that turn on, and off their LEDs seemingly in perfect synchronization, while also proving that neither device is holding the MOSI line hostage.

And... here it is in action:

Success! No tri-state buffer needed.

Additionally, to improve sound-quality, I added some more filtering on the output pin. For such low-cost and low-power parts, it was starting to sound really good... and loud!

This pretty much constituted the entirety of the project... sound, lights, bidirectional communication... I feel like I'm forgetting something, though.

Oh, right. Power.

Yeah, I forgot... I gotta run all this off of just 2 AA batteries. Since I need 3.3v for most of my electronics, and 5v for the LM386, but the AA batteries provide at most 3v... I need to boost the voltage somehow.

I did some digging for any battery-management chips that may exist, that are cheap enough for my project... and stumbled upon a magical unicorn called the AAT1217.

Easy-to-use with just 6 pins, an external inductor, and some resistors to set the output voltage (and an external schottky diode if you're setting it above 4.5v), this baby will squeeze every last drop of juice out of your choice of either a single AA battery, two AA batteries, or a single disposable Lithium-Ion battery, with up to 93% efficiency... all in the same package as the PIC10F220 and the MCP4725. Perfect!

My strategy was to set this to 5v to supply the LM386 with what it needs, and then use a linear regulator to step it back down to 3.3v. In the grand scheme of things, that's a trivial change, and any regulator worth its salt should be able to handle that with almost no energy loss.

My regulator of choice: AMS1117

Funny enough, these things are in the dev boards I ordered... as well as like, every Arduino ever made. Pretty common, and very cheap!

With all this planned out, I set to work creating the schematic for the whole circuit board. Something I made sure to include was a jumper to cut power to all the lasers, so that I could completely remove the risk of damaging my eyes when I was working on the board.

Dang, that's a whole lot more complicated than my first board design. Time to lay it out!

I tried to compartmentalize different parts... power in the lower right, audio amplifier in the top right, all the connectors on the right edge so they point towards the back of the gun... laser holder on the bottom, with 3mm drill holes... 5 connectors, all in a row for the 5 lasers, with the one that can be blinked marked with a *. I had trouble routing all the traces away from the STM32, so I flipped it to the backside of the board and broke it out with a bunch of vias, so I had enough room to work.

After a few weeks, the boards arrived in the mail:

Fun fact: Matte Black doesn't cost any more than Green, at JLCPCB. Man, it looks good! And the CK is so shiny...

Because these boards are so complex, and I never tested the AAT1217 before designing it in... I decided it would be best to assemble this in parts, starting with the lower right power circuitry and the lasers.

And... Hey! It works!

This was with fresh batteries, supplying very nearly 3v... But for fun, I tested this with batteries that wouldn't even run my analog wall clock, and the laser powered up just fine at the same brightness as the fresh batteries. Whether or not the amplifier will still work with batteries this dead remains to be seen.

The next parts of the board, I assembled in steps. The very next thing I soldered was the STM32. I wanted to make sure that was getting clean enough power to talk to the ST-Link, over the programming header on the board. The "RST" pin you see towards the bottom of the header isn't actually needed. I included it just in case I needed to force-reset the chip for any reason, but during normal programming/debugging operation, the STM32 accepts a "software reset" - a special sequence of bits that tells the internal firmware of the STM32 that it's time to go into reset mode. When powered off the batteries, the ST-Link only needs 3 wires: DIO, CLK, and GND.

Next was the MCP4725 and associated 4.7kΩ I2C pull-up resistors. I wanted to make sure that, before I assembled the amplifier, I was getting a good output from the DAC to limit how much troubleshooting I'd have to do, should this board not produce sound as expected.

After I verified that the MCP4725 was outputting the voltages I told it, at speeds comparable to what I need for clear audio, I went ahead and assembled the amplifier. I had a test from earlier that I already made to play a small soundbyte from the internal STM32 flash... After loading that up, and plugging in the speaker... it sounded great!

Now that I knew sound worked at the most basic level, I knew I could go ahead and get the flash chip programmed with all the voice lines, and try playing WAV files from that.

Essentially, I just stacked everything together end-to-end... but I knew that by just doing that, it'd be hard to see in the hex editor where individual soundbytes were in the file. So, I came up with a way to delineate each one by driving the amplitude up to 255 between each voice line. In audacity, it looks like this:

In the hex editor, it looks like this:

That wall of FF's you see there is my marker for where the sound data ends, and at the end of the wall is the next voice line. It continues on past the bottom of the window a bit, so it's impossible to miss while I'm scrolling. This way, I've eliminated guesswork for where each individual sound file is located... and I don't have to re-guess if I decide to switch out or remove a voice line from the chip. It's plain-as-day to see what I'm working with. Also, to quash any concerns about "wasting bytes"... These voice lines barely use 1/4 of the chip's total capacity. I've got plenty of room to spare for making things easy for myself.

After proving that I could play audio from the chip through the DAC and amplifier... I moved on to soldering the radio onto the SPI bus. Once the radio was on, I loaded up another program of mine that tests bidirectional communication with another radio on a breadboard, to trigger playing a sound file. Something unusual happened, though... Unlike my breadboard tests with an (in theory) identical circuit, the assembled board refused to transmit back to the other radio, after the sound file finished playing. "This is odd," I thought, because in the program, it's supposed to wait for the broadcast... What's going on?

My initial thought was that the power requirements were too much... but the issue persisted even after I unplugged the speaker. What gives? My next thought was that maybe I really did need that tri-state buffer, after all. Unpredictable chips causing weird behavior, and such... But after some tests with reading the status register of the nRF24L01, I proved that the flash chip was handing over control of the MISO line like it should. What in the world was going on here?! Faulty radio? Using my breadboard prototype, I was quickly able to test all 9 other radios in my pack of 10 from Amazon, and all worked just fine. The likelihood that I picked the single bad one at random from the bag was too small for me to really consider... Due to the proximity of the radio's pins to the flash chip, it would be too risky to remove it... So I opted to try using jumper wires to test the radio I had soldered onto my board. I had difficulty getting one jumper on the MISO pin, due to a glob of solder getting in the way. After heating it up, and moving it down to the base of the pin, an idea popped into my head: "What if that just fixed it, right there?"

So I turned it on, and boom! Bidirectional communication restored. All it was, was a bad solder joint on one of the data pins! What a relief. With that final outlying problem solved, I had in my hands an (almost) fully working board. All that was left was to get the LEDs, transistors, and the Trigger connector soldered, and crimp some more JST connectors onto my lasers!

Next, I needed to get the front-facing LEDs, transistors, and trigger switch port added on.

Oddly enough, I think the transistors ended up being the most difficult part to solder by far. I've actually never soldered a TO-92 package component before, so I was woefully unprepared for the challenges I encountered. These things dissipate as much heat as possible by design... and when a glob of solder comes into contact with one of the legs, it pretty much instantly cools and solidifies before it has a chance to bond with the board. This leaves you with legs that look soldered... but actually have no electrical contact with the board whatsoever, and can be moved as easily as a loose tooth. Reworking is almost impossible, because any heat you add to the problem-solder gets immediately transferred to the transistor casing. Too much heat kills the transistor, which means you have to heat it up an absurd amount to get the solder glob to even budge. Adding more solder to try to rectify the problem doesn't work either, because I've found it almost always ends up contacting a neighboring pad.

I learned all this after killing around 6 transistors on the second board, trying to get them to stick.

When you do kill a transistor by trying to solder it too much, it is extremely difficult to remove. Because the legs cool very quickly, pulling the entire length out through the hole isn't really an option. I had to resort to cutting the legs as short as possible, and then simultaneously heating them up, and torquing them through with brute force. Actually, on that second board, a fragment of the Base pin of a broken transistor got permanently stuck in the hole, and I was forced to solder the new leg directly to the resistor.

As far as soldering the rest of the legs... I came up with a technique that seemed to work pretty reliably, and it's one that I'll likely use for future TO-92 soldering; if you cut the legs flush with the holes before soldering, and just "cap" each one with a small glob of solder... it mitigates almost every issue mentioned above. You still only get "one shot," and it still has a good chance of making contact with a neighboring pad, but it's the best I've been able to come up with so far.

After this was all said and done with, I fired up the second board to make sure it worked as intended. But... it didn't, in one very weird aspect. One of the LEDs on the front was really, really dim when it was supposed to be off... and only got dimmer when it was supposed to be on! What in the world?! I was convinced I had managed to solder the transistors withoug killing them, this time... so what was happening? I measured the voltage at the base resistor of both of the other transistors... 3.3v, just as they should be. Then, I measured it at the base resistor of the problem transistor... 0v! The problem must be up-stream somewhere. Is the other end of the resistor getting 3.3v? Yes... and that goes directly to the microcontroller. And... that pin looks fine, from a quick visual inspection. Uh oh, did my transistor-shenanigans end up killing a GPIO pin? A quick reading of the pin with my multimeter shows that it's putting out 3.3v on command... so, no, it's fine. Must be a problem with the pad. But, quickly checking the continuity of the resistor showed that it was good all the way through! How could this be?!

After much troubleshooting, the answer was a little embarrassing... the very, very slight pressure from the multimeter probe was forcing the pin to make contact with the pad, and give a false impression of reliable continuity. One swipe from my fine-tipped soldering iron connected the pad properly, and the LED lit up and turned off just fine.

That's the one thing I really dislike about these STM32s... The dual-inline package has such fine pins that it seems to almost never go down without needing some sort of tedious rework. I'll have to try out a quad flat package in a future project to see if that's easier.

In the meantime, I've also figured out an even easier/more reliable method of soldering TO-92's... just use solder paste, and heat them up like you would an SMD component. The solder paste flows exactly where it needs to, and provides a very secure bond with the board. No hassle, and almost guaranteed to not kill the transistor.

Eventually, I got all 4 boards finished up, and ready to program! Still gotta finish all those lasers and cables up, though.

Meanwhile on the mechanical side, things were (literally) starting to take shape.

Here are the bottoms of the handles that house part of the trigger assembly, and form the very bottom of the battery housing...

And here are some various small parts for the internals of the gun, like the Speaker Tray, PCB Tray, the two halves of the 5-Laser-Holder that mounts to the two holes on the PCB, and some general support material.

Some bigger parts have also been printed, such as one half of the front barrel which houses the PCB, and the decorative handle on the back.

Inside, the slot for the tray, and the cavity for the front-facing fiber optic cable look great!

Back to PCB-land for a moment; it's firmware time!

Now, the only human interface our guns have is the trigger... so that means that the logical distinction of which of the two boards is in charge of making decisions like what channel to communicate on, when to reload, and which voice line to play after the reload needs to be made in software, and not with a jumper or DIP switch or something.

The best way I could think of to describe how the two boards need to behave was to make a flowchart:

What I've made here is called a "Finite-State Machine", which is a machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. This computational paradigm is, in practice, insanely reliable and thus used extensively in industrial automation and "black-box" consumer electronics.

Check out my main.c showing how I implemented this logic. Commented to enhance readibility.

And, to see this whole thing in action, check out this video I made of all 4 boards operating in the same general vicinity with no interference:

With the electronics completed, it was back to getting all the parts 3D printed.

A second 3D printer was purchased to help cope with the amount of printing, an Ender 3 Pro by Creality. After some setup, it was off to the races (for only $200!)

Eventually, all the pieces needed for one of the guns were printed!

It was time to do a test fit to see how everything went together. While it looks like a very complicated assembly process, the pieces are actually quite intuitive to put together since they're all so unique.

See, very simple. It's not glued together yet, this is just a test-fit to see how it all sizes up and if there's any parts that need a little TLC. But everything fit nice and snug, and lined up the first time!

And, of course, ruler for scale:

Other parts for the costume started to get printed as well, like various pieces of Reaper's 4 belts:

And, here it is for size:

Next, it was time for sanding and a round of paint! Time to make these pieces really look good!

Before:

After:

Black was the chosen base coat, to be followed by silver in applicable areas.

Together, they make a really neat effect!

All of the parts came out really shiny, and they look amazing.

Next, it was time for the big prints! The gauntlets were to be printed in two parts... a smaller, lower wristpiece... and a gigantic upper forearm piece that would take many hours and have a relatively high probability of failure.

But... dang! Fresh off the printer, the first one looks amazing! It's a little angular due to having to manually stitch some polygons together in Cinema 4D, but that'll clean up after some sanding.

So, arms are coming along nicely, but now it's time for the legs! We've got some boots to make. But I don't feel like making a boot from scratch, so let's find an existing pair to build off of. We had an old pair of motorcycle boots that resembled the shape of Reaper's boots that we could add parts to. But... the parts in their current form won't fit the boot perfectly, and I'm not willing to sit there printing adjustment after adjustment just to hone in on the right shape. I need to know that the part I'm printing is going to fit, 100%. So, how do we do this?

An idea I had was to use photogrammetry to "scan" the boots into Cinema 4D, and then mold the pieces virtually before printing.

We took video of all angles of the boots to give Agisoft Photoscan every possible detail to work off of. In After Effects, I keyed out the pink backdrop to generate an alpha channel mask for every frame of the video, which was then exported as a PNG sequence with alpha channel. That gave us about 1000 camera angles to work with, which in my experience should be plenty to get an accurate model.

After a few nights of computation, Photoscan spit this out:

Beautiful! I can work with this.

After a bit of work, I made this in Cinema 4D:

Yeah, it clips a little bit... but boots aren't completely solid, so these parts should fit.

And... It definitely looks like they will! No wasted PLA plastic here. This method totally works!

Meanwhile, while all this is going on, the PCBs have arrived at their final destination and are ready to be mated to the 3D printed gun for the first time.

And... there it is! Sound works, the LEDs line up with the barrels properly, and it's definitely loud and bright enough!

The connection between the radio and microcontroller on the PCB is a little shaky, though, which is something I encountered on my bench tests... It may be necessary to do a "revision 2" of the boards in order to remedy the issue and make it more reliable.