https://medium.com/towardsdev/concurrent-write-problem-afe4dbe47ae7

Concurrency control is one of the most challenging aspects of software development. Sometimes, we have a tendency to wishful thinking and naive beliefs that our advanced toolkit like a web framework, a database or an ORM solve all our issues seamlessly underhood. However, when we tackle non-trivial problem (like concurrent write), we have to demonstrate some understanding how these tools genuinely work (and maybe why they are configured in the specific way).

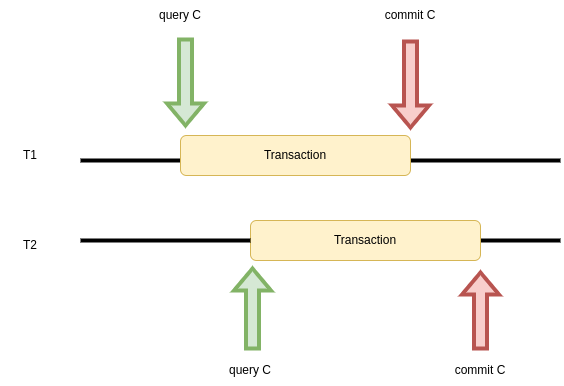

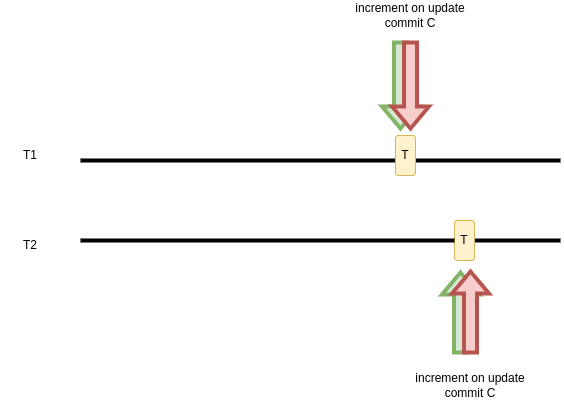

Suppose we have a PostgresSQL database with a table example that has an important integer column (important_counter) and two separated transactions query important_counter value from row with id = 1 at some point and want to increase the value at approximately the same time.

Assuming that row initial value for the important_counter is 0, what state of the important_counter do you expect when transactions commit successfully their changes?

A. important_counter = 2 - both transactions (T1 and T2) have managed to increase counter sequentially.

B. important_counter = 1 - both transactions (T1 and T2) have managed to increase counter independently starting from 0 value, but one transaction's commit overwrites commit of the other one.

C. important_counter = 1 - one transaction (T1) committed changes, while the other one (T2) got an exception due to concurrent row access.

There is no simple answer for this question, because it depends on the database configuration and our SELECT / UPDATE strategies. If we use default configuration and transaction scheme that looks like:

BEGIN;

SELECT important_counter FROM example WHERE id = 1;

# some application logic checking

# whether important_counter should be increased

UPDATE example SET important_counter = <new_value>

WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;the result would be an option B and this situation is usually called lost update. Surprised?

Relational databases (like PostgreSQL) are usually ACID-complaint and it means transactions are processed in atomic, consistent, isolated and durable way. For our case, isolation property should be concerned, because it refers to the ability of a database to run concurrent transactions. There are 4 different isolation levels:

- read uncommitted - a transaction can see committed and uncommitted changes from other concurrent transactions.

- read committed - a transaction can see only committed changes from other concurrent transactions. However, citing PostgreSQL docs : Also note that two successive SELECT commands can see different data, even though they are within a single transaction, if other transactions commit changes after the first SELECT starts and before the second SELECT starts.

- repeatable reads - a transaction can see only committed changes from other concurrent transactions. The difference between read committed and repeatable reads is that two successive SELECT commands in latter one would always return the same data.

- serializable - most strict one. Disable concurrency by executing transaction one after another, serially.

The default isolation level for PostgreSQL is read committed (to check an isolation level you can run a query SHOW TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL). Because of that T1 and T2 transactions queried committed value of important_counter that was 0 and both increased it by 1 without any exceptions.

So, how we can change this behavior to have counter increased serially or at least get an exception that allow us to retry the transaction?

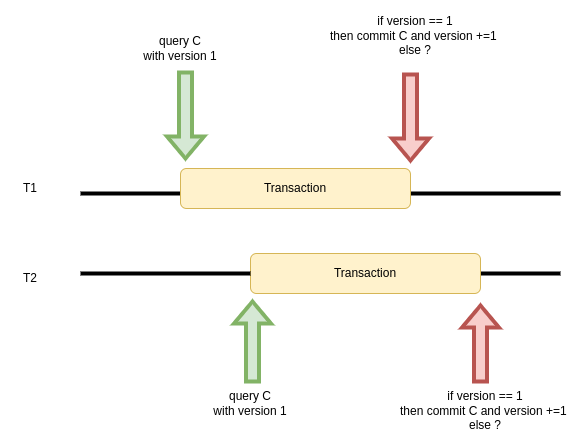

First group of solutions is optimistic locking. In fact, it does not lock rows for concurrent access but optimistically assumes that a row would not be changed by another transaction. However, if the row does change by concurrent process, modification will fail and application can handle it. There are two ways how to implement it:

- using a

version_numbercolumn (it can be integer, timestamp or hash). Update is possible only if theversion_numberat commit stage is equal to theversion_numberfrom query time. Each commit should update also theversion_numberof the row. At application side we can check if the row was updated and make proper action.

BEGIN;

SELECT important_counter, version_number FROM example

WHERE id = 1;

# some application logic checking

# whether important_counter should be increased

UPDATE example SET important_counter = <new_value>, version_number = version_number + 1

FROM example

WHERE id = 1 AND version_number = <version_number_from_select>;

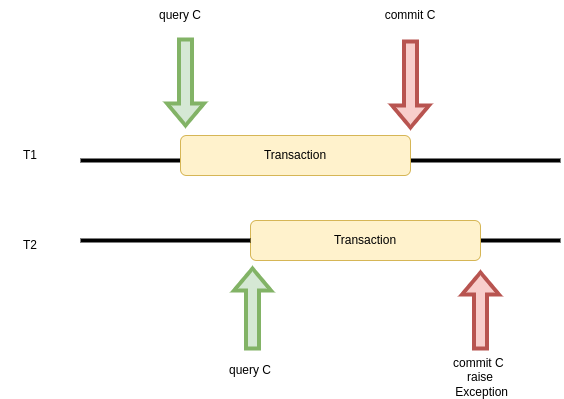

COMMIT;- by switching to repeatable read isolation level. When T2 tries to commit changes after successfull T1 commit, an exception is raised (worth to mention it would not be raised if T1 is rollbacked). Again, we can decide how to handle the exception.

SET TRANSACTION REPEATABLE READ;

BEGIN;

SELECT important_counter FROM example WHERE id = 1;

# some application logic checking

# whether important_counter should be increased

UPDATE example SET important_counter = <new_value>

WHERE id = 1;

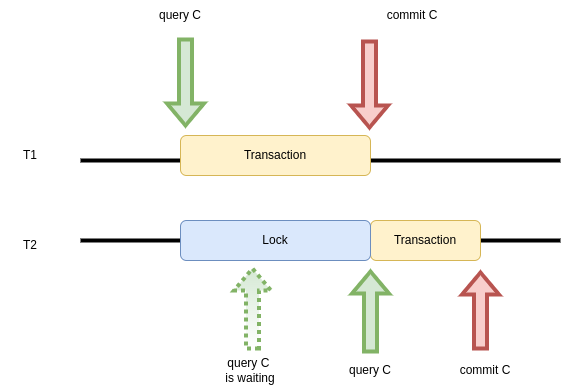

COMMIT;Pessimistic approach prevents simultaneous modification of a record by placing a lock on it when one transaction start an update process. A concurrent transaction that want to access locked row have two options:

- wait until transaction T1 is completed.

BEGIN;

SELECT important_counter FROM example

WHERE id = 1 FOR UPDATE;

# some application logic checking

# whether important_counter should be increased

UPDATE example SET important_counter = <new_value>

WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;- break process and raise an exception that should be handled.

BEGIN;

SELECT important_counter FROM example

WHERE id = 1 FOR UPDATE NOWAIT;

# some application logic checking

# whether important_counter should be increased

UPDATE example SET important_counter = <new_value>

WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;There is also a simple solution when our goal is only to increment a value. However, it would work only if we do not need a part of application logic check, so update process is not separated from query that can be not up-to-date.

BEGIN;

UPDATE example SET important_counter = important_counter + 1

WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;We have showed some examples how to handle concurrent update issues. However, optimistic or pessimistic locking is not always the best solution. Sometimes, you encounter concurrency problems because of bad design of your system. When your class (model / table) break SRP (Single Responsibility Principle) by keeping data and behavior that are not cohesive, you may encounter many overlapping transactions that want modify different data corresponding to the same record. In that case, above strategies ease your problem a little bit but do not target genuine reason of your troubles.