A linked list implementation with unique features and an extended list of constant time methods providing high performance traversals and mutations.

Both doubly and singly lists are provided as generic variants of the core struct List. It is sufficient to know the four variants:

DoublyListandSinglyListDoublyListLazyandSinglyListLazy- Lazy suffix corresponds to lazy memory reclaim and will be explained in the indices section.

Some notable features are as follows.

Link lists are self organizing to keep the nodes close to each other to benefit from cache locality. Further, it uses safe direct references without an additional indirection to traverse through the nodes.

We observe in benchmarks that DoublyList is significantly faster than the standard linked list.

A. Benchmark & Example: Mutation At Ends

In doubly_mutation_ends.rs benchmark, we first push elements to a linked list until it reaches a particular length. Then, we call

push_backpush_frontpop_backpop_front

in a random alternating order. We observe that DoublyList is around 40% faster than std::collections::LinkedList.

The following example demonstrates the simple usage of the list with mutation at its ends.

use orx_linked_list::*;

let mut list = DoublyList::new();

list.push_front('b');

list.push_back('c');

list.push_front('a');

list.push_back('d');

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']));

assert_eq!(list.pop_back(), Some('d'));

assert_eq!(list.pop_front(), Some('a'));

assert_eq!(list.front(), Some(&'b'));

assert_eq!(list.back(), Some(&'c'));

assert_eq!(list.len(), 2);B. Benchmark & Example: Iteration or Sequential Access

In doubly_iter.rs benchmark, we create a linked list with insertions to the back and front of the list in a random order. Then, we iter() over the nodes and apply a map-reduce over the elements.

We observe that DoublyList iteration is around 25 times faster than that with std::collections::LinkedList.

The significance of improvement can further be increased by using DoublyList::iter_x() instead, which iterates over the elements in an arbitrary order. Unordered iteration is not suitable for all use cases. Most reductions or applying a mutation to each element are a couple of common examples. When the use case allows, unordered iteration further provides significant speed up.

Linked lists are all about traversal. Therefore, the linked lists defined in this crate, especially the DoublyList, provide various useful ways to iterate over the data:

iter() |

from front to back of the list |

iter().rev() |

from back to front |

iter_from(idx: &DoublyIdx<T>) |

forward starting from the node with the given index to the back |

iter_backward_from(idx: &DoublyIdx<T>) |

backward starting from the node with the given index to the front |

ring_iter(pivot_idx: &DoublyIdx<T>) |

forward starting from the pivot node with the given index until the node before the pivot node, linking back to the front and giving the list the circular behavior |

iter_links() |

forward over the links, rather than nodes, from front to back |

iter_x() |

over elements in an arbitrary order, which is often faster when the order is not required |

As typical, above-mentioned methods have the "_mut" suffixed versions for iterating over mutable references.

Example: Iterations or Traversals

use orx_linked_list::*;

let list: DoublyList<_> = (0..6).collect();

let res = list.iter().copied().collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]);

let res = list.iter().rev().copied().collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, [5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]);

let res = list.iter_links().map(|(a, b)| (*a, *b)).collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, [(0, 1), (1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4), (4, 5)]);

let res = list.iter_x().copied().collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]); // deterministic but arbitrary order

// using indices (see the indices section for details)

let idx: Vec<_> = list.indices().collect();

let res = list.iter_from(&idx[3]).copied().collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, [3, 4, 5]);

let res = list

.iter_backward_from(&idx[3])

.copied()

.collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, [3, 2, 1, 0]);

let res = list.ring_iter(&idx[3]).copied().collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, [3, 4, 5, 0, 1, 2]);Due to the feature of the Recursive growth strategy of the underlying SplitVec that allows merging vectors and the nature of linked lists, appending two lists is a constant time operation.

See append_front and append_back.

Example: Merging Linked Lists

use orx_linked_list::*;

let mut list = DoublyList::new();

list.push_front('b');

list.push_front('a');

list.push_back('c');

let other = DoublyList::from_iter(['d', 'e'].into_iter());

list.append_front(other);

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['d', 'e', 'a', 'b', 'c']));DoublyIdx<T> and SinglyIdx<T> are the node indices for doubly and singly linked lists, respectively.

A node index is analogous to usize for a slice (&[T]) in the following:

- It provides constant time access to any element in the list.

It differs from usize for a slice due to the following:

usizerepresents a position of the slice. Say we have the slice['a', 'b', 'c']. Currently, index 0 points to elementa. However, if we swap the first and third elements, index 0 will now be pointing tocbecause theusizerepresents a position on the slice.- A node index represents the element it is created for. Say we now have a list

['a', 'b', 'c']instead andidx_ais the index of the first element. It will always be pointing to this element no matter how many times we change its position, its value, etc.

Knowing the index of an element enables a large number of constant time operations. Below is a toy example to demonstrate how the index represents an element rather than a position, and illustrates some of the possible O(1) methods using it.

Example: Constant Time Access Through Indices

use orx_linked_list::*;

let mut list = DoublyList::new();

list.push_back('c');

list.push_front('b');

let idx = list.push_front('a');

let idx_d = list.push_back('d');

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']));

// O(1) access / mutate its value

assert_eq!(list.get(&idx), Some(&'a'));

*list.get_mut(&idx).unwrap() = 'o';

list[&idx] = 'X';

assert_eq!(list[&idx], 'X');

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['X', 'b', 'c', 'd']));

// O(1) move it around

list.move_to_back(&idx);

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['b', 'c', 'd', 'X']));

list.move_prev_to(&idx, &idx_d);

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['b', 'c', 'X', 'd']));

// O(1) start iterators from it

let res = list.iter_from(&idx).copied().collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, ['X', 'd']);

let res = list.iter_backward_from(&idx).copied().collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, ['X', 'c', 'b']);

let res = list.ring_iter(&idx).copied().collect::<Vec<_>>();

assert_eq!(res, ['X', 'd', 'b', 'c']);

// O(1) insert elements relative to it

list.insert_prev_to(&idx, '>');

list.insert_next_to(&idx, '<');

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['b', 'c', '>', 'X', '<', 'd']));

// O(1) remove it

let x = list.remove(&idx);

assert_eq!(x, 'X');

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['b', 'c', '>', '<', 'd']));

// what happens to the index if the element is removed?

assert_eq!(list.get(&idx), None); // `get` safely returns None

// O(1) we can query its state

assert_eq!(list.is_valid(&idx), false);

assert_eq!(list.idx_err(&idx), Some(NodeIdxError::RemovedNode));

// list[&idx] = 'Y'; // panics!Each method adding an element to the list returns the index created for that particular node.

Example: Individual node indices from push & insert

use orx_linked_list::*;

let mut list = DoublyList::new();

let c = list.push_back('c');

let b = list.push_front('b');

let a = list.insert_prev_to(&b, 'a');

let d = list.insert_next_to(&c, 'd');

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']));

let values = [list[&a], list[&b], list[&c], list[&d]];

assert_eq!(values, ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']);Alternatively, we can collect all indices at once using the indices method.

Example: All node indices from indices()

use orx_linked_list::*;

let mut list = DoublyList::new();

list.push_back('c');

list.push_front('b');

list.push_front('a');

list.push_back('d');

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']));

let idx: Vec<_> = list.indices().collect();

assert_eq!(list[&idx[2]], 'c');

assert_eq!(list.remove(&idx[1]), 'b');

assert_eq!(list.remove(&idx[3]), 'd');

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals(['a', 'c']));Traditionally, linked lists provide constant time access to the ends of the list, and allows mutations pushing to and popping from the front and the back (when doubly). Using the node indices, the following methods can also be performed in O(1) time:

- accessing (reading or writing) a particular element (

get,get_mut) - accessing (reading or writing) a the previous or next of a particular element (

next_of,prev_of,next_mut_of,prev_mut_of) - starting iterators from a particular element (

iter_from,iter_backward_from,ring_iter,iter_mut_from,iter_mut_backward_from,ring_iter_mut) - moving an element to the ends (

move_to_front,move_to_back) - moving an element to previous or next to another element (

move_next_to,move_prev_to) - inserting new elements relative to a particular element (

insert_next_to,insert_prev_to) - removing a particular element (

remove)

Indices enable slicing the list, which in turns behaves as a list reflecting its recursive nature.

Example: Slicing linked lists

use orx_linked_list::*;

let mut list: DoublyList<_> = (0..6).collect();

let idx: Vec<_> = list.indices().collect();

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]));

// slice

let slice = list.slice(&idx[1]..&idx[4]);

assert!(slice.eq_to_iter_vals([1, 2, 3]));

assert_eq!(slice.front(), Some(&1));

assert_eq!(slice.back(), Some(&3));

assert_eq!(slice.iter().copied().collect::<Vec<_>>(), [1, 2, 3]);

assert_eq!(slice.iter().rev().copied().collect::<Vec<_>>(), [3, 2, 1]);

// slice-mut

let mut slice = list.slice_mut(&idx[1]..&idx[4]);

for x in slice.iter_mut() {

*x += 10;

}

assert!(slice.eq_to_iter_vals([11, 12, 13]));

slice.move_to_front(&idx[2]);

assert!(slice.eq_to_iter_vals([12, 11, 13]));

*slice.back_mut().unwrap() = 42;

assert!(list.eq_to_iter_vals([0, 12, 11, 42, 4, 5]));How important are the additional O(1) methods?

- In this talk here, Bjarne Stroustrup explains why we should avoid linked lists. The talk nicely summarizes the trouble of achieving the appealing constant time mutation promise of linked list. Further, additional memory requirement due to the storage of links or pointers is mentioned.

- Likewise, there exists the following note in the documentation of the

std::collections::LinkedList: "It is almost always better to use Vec or VecDeque because array-based containers are generally faster, more memory efficient, and make better use of CPU cache."

This crate aims to overcome the concerns with the following approach:

- Underlying nodes of the list are stored in fragments of contagious storages. Further, the list is self organizing to keep the nodes dense, rather than scattered in memory. Therefore, it aims to benefit from cache locality.

- Provides a safe node index support which allows us to jump to any element in constant time, and hence, be able to take benefit from mutating links, and hence the sequence, in constant time.

▶ Actually, there is no choice between a Vec and a linked list. They are rarely interchangeable, and when they are, Vec must be the right structure.

▶ There is also no choice between a VecDeque and a linked list. VecDeque is very efficient when we need a double ended queue. However, we need a linked list when we need lots of mutations in the sequence and positions of elements. They solve different problems.

For instance, a DoublyList with indices is a better fit for a problem where we will continuously mutate positions of elements in a collection, moving them around. A very common use case occurs due to the classical traveling salesman problem where we keep changing positions of cities with the aim to find shorter and shorter tours.

See the example in tour_mutations.rs.

cargo run --release --example tour_mutations -- --num-cities 10000 --num-moves 10000

The challenge is as follows:

- We have a tour of n cities with ids 0..n.

- We have an algorithm that searches for and yields improving moves (not included in the benchmark).

- In the data structure representing the tour, we are required to implement

fn insert_after(&mut self, city: usize, city_to_succeed: usize)method which is required to move the city after the city_to_succeed.

Although this seems like a primitive operation, it is challenging to implement with a standard vector. Details of an attempt can be found in the example. In brief, one way or the other, it is not clear how to avoid the O(n) time complexity of the update.

With a combination of DoublyList and indices; on the other hand, the method can be very conveniently implemented and it leads to a constant time update. Linked list is the naturally fitting tool for this task. The complete implementation is as follows:

use orx_linked_list::*;

struct City {

id: usize,

name: String,

coordinates: [i32; 2],

}

struct TourLinkedList {

cities: DoublyList<City>,

idx: Vec<DoublyIdx<City>>,

}

impl TourLinkedList {

fn insert_after(&mut self, city: usize, city_to_succeed: usize) {

let a = &self.idx[city];

let b = &self.idx[city_to_succeed];

self.cities.move_next_to(&a, &b);

}

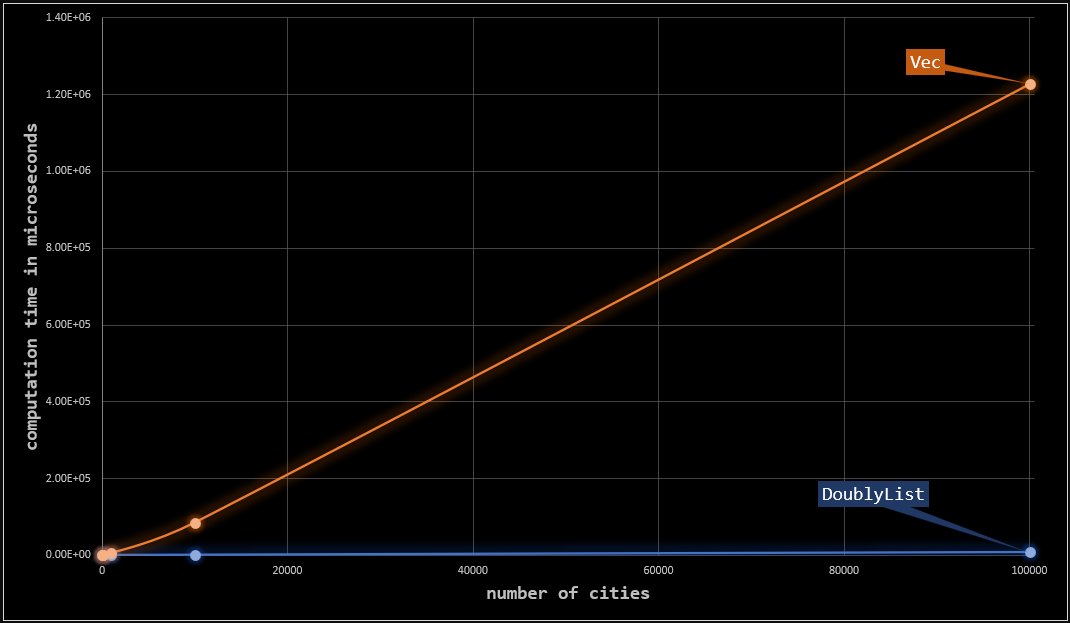

}Although clear from the worst time complexity of the implementations, doubly_shuffling_around.rs benchmark demonstrates the dramatic difference. At each setting, we perform 10k insert_after moves with tours of different lengths. The following table summarizes the required time in microseconds for each setting.

As mentioned, node indices are associated with elements rather than positions.

- The linked list can provide safe access through node indices due to the fact that the underlying storage is a

SplitVecwhich implementsPinnedVec, keeping the memory positions of its elements unchanged, unless they are explicitly changed. - Therefore, the list is able to know if a node index is pointing to a valid memory position belonging to itself, and prevents to use a node index created from one list on another list:

get,is_valid,idx_errreturns None, false andNodeIdxErr::OutOfBounds, respectively.

- Further, when an element is removed from the list, its position is not immediately filled by other elements. Therefore, the index still points to the correct memory position and the list is able to know that the element is removed.

get,is_valid,idx_errreturns None, false andNodeIdxErr::RemovedNode, respectively.

Clearly, such a memory policy leaves gaps in the storage and utilization of memory becomes important. Therefore, the linked lists are self-organizing as follows:

- Whenever an element is removed, the utilization of nodes is checked. Node utilization is the ratio of active nodes to occupied nodes.

- Whenever the utilization falls below a certain threshold (75% by default), positions of closed nodes are reclaimed and utilization is brought back to 100%.

When, a node reorganization is triggered, node indices collected beforehand become invalid. The linked lists, however, have a means to know that the node index is now invalid by comparing the so called memory states of the index and list. If we attempt to use a node index after the list is reorganized and the index is invalidated, we safely get an error:

get,is_valid,idx_errreturns None, false andNodeIdxErr::ReorganizedCollection, respectively.

In summary, we can make sure whether or not using a node index is safe. Further, we cannot have an unchecked / unsafe access to elements that we are not supposed to.

It sounds inconvenient that the indices can implicitly be invalidated. The situation, however, is not complicated or unpredictable.

- First, we know that growth can never cause reorganization; only removals can trigger it.

- Second, we have the lazy versions of the lists which will never automatically reorganize nodes. Collected indices will always be valid unless we explicitly call

reclaim_closed_nodes. - Third, it is free to transform between auto-reclaim and lazy-reclaim modes.

Therefore, we can have full control on the valid lifetime of our indices.

Controlling Validity of Node Indices

use orx_linked_list::*;

// default -> auto-reclaim mode

let mut list: DoublyList<_> = DoublyList::new();

// mutate the list in auto-reclaim-mode

for i in 0..60 {

list.push_back(i);

}

// the following removals will lead to one implicit/auto

// node reclaims operation keeping node utilization high

for i in 0..20 {

match i % 2 == 0 {

true => list.pop_front(),

false => list.pop_back(),

};

}

assert_eq!(list.len(), 40);

// collect indices

let idx: Vec<_> = list.indices().collect();

assert_eq!(idx.len(), 40);

// shift to lazy-reclaim mode to make sure that the indices stay valid

let mut list: DoublyListLazy<_> = list.into_lazy_reclaim();

// mutate & move things around

for i in 0..list.len() {

match i % 3 {

0 => list.move_to_front(&idx[i]),

1 => {

let j = (i + 1) % list.len();

list.move_next_to(&idx[i], &idx[j]);

}

_ => list[&idx[i]] *= 2,

}

}

// pop half of the nodes -> no reorganization

for i in 0..(list.len() / 2) {

match i % 2 == 0 {

true => list.pop_back(),

false => list.pop_front(),

};

}

// remove 10 more by indices -> no reorganization

let mut num_removed = 0;

for idx in &idx {

// if not yet removed

if list.is_valid(&idx) {

list.remove(&idx);

num_removed += 1;

if num_removed == 10 {

break;

}

}

}

// we now must have 40 - 20 - 10 = 10 elements in the list

assert_eq!(list.len(), 10);

// but pointers of 40 of the original indices are still valid

// despite all removals, the nodes are never reorganized!

assert_eq!(idx.len(), 40);

// * 10 of them are pointing to remaining elements

// * 30 of them are pointing to gaps

let num_active = idx.iter().filter(|x| list.is_valid(x)).count();

let num_removed = idx

.iter()

.filter(|x| list.idx_err(x) == Some(NodeIdxError::RemovedNode))

.count();

assert_eq!(num_active, 10);

assert_eq!(num_removed, 30);

// now that we completed heavy mutations on sequence, we can reclaim removed nodes

list.reclaim_closed_nodes();

// this explicitly invalidates all indices

let num_valid_indices = idx.iter().filter(|x| list.is_valid(x)).count();

assert_eq!(num_valid_indices, 0);

// and brings utilization to 100%

let utilization = list.node_utilization();

assert_eq!(utilization.num_active_nodes, 10);

assert_eq!(utilization.num_closed_nodes, 0);

// now we can switch back to the auto-reclaim mode

let list = list.into_auto_reclaim();Contributions are welcome! If you notice an error, have a question or think something could be improved, please open an issue or create a PR.

This library is licensed under MIT license. See LICENSE for details.