Instructors

Simon Prochnik

Sofia Robb

Table of Contents

- Big Picture

- Unix

- Unix 1

- Unix Overview

- The Basics

- Logging into Your Workstation

- Bringing up the Command-Line

- OK. I've Logged in. What Now?

- Command-Line Prompt

- Issuing Commands

- Command-Line Editing

- Wildcards

- Home Sweet Home

- Getting Around

- Essential Unix Commands

- Getting Information About Commands

- Finding Out What Commands are on Your Computer

- Arguments and Command Line Switches

- Spaces and Funny Characters

- Useful Commands

- Manipulating Directories

- Networking

- Standard I/O and Redirection

- A Simple Example

- Redirection Meta-Characters

- Filters, Filenames and Standard Input

- Standard I/O and Pipes

- More Pipe Idioms

- Advanced Unix

- Link to Unix 1 Problem Set

- Unix 2

- Text Editors

- Git for Beginners

- The Big Picture.

- Collaboration

- Storing Versions

- Restoring Previous Versions

- Backup

- The Details

- The Basics

- Creating a new repository

- Cloning a Repository

- Bringing Changes in Remote to your Local Repository

- Keeping track of differences between local and remote repositories

- Links to Slightly less basic topics

- Link To Unix 2 Problem Set

- Unix 1

- Python

- Python 1

- Python 2

- Python 3

- Sequences

- What functions go with my object?

- Strings

- Quotation Marks

- Strings and the print() function

- Errors and Printing

- Special/Escape Characters

- Concatenation

- The difference between string and integer

- Determine the length of a string

- Changing String Case

- Find and Count

- Find and Replace

- Extracting a Substring, or Slicing

- Locate and Report

- Other String Methods

- String Formatting

- Lists and Tuples

- Link to Python 3 Problem Set

- Python 4

- Python 5

- Python 6

- Regular Expressions

- Individual Characters

- Character Classes

- Anchors

- Quantifiers

- Variables and Patterns

- Either Or

- Subpatterns

- Using Subpatterns Inside the Regular Expression Match

- Using Subpatterns Outside the Regular Expression

- Get position of the subpattern with finditer()

- Subpatterns and Greediness

- Practical Example: Codons

- Truth and Regular Expression Matches

- Using Regular expressions in substitutions

- Using subpatterns in the replacement

- Regular Expression Option Modifiers

- Link to Python 6 Problem Set

- Regular Expressions

- Python 7

- Python 8

- Python 9

- Bioinformatic Analysis and Tools

Instructors

Simon Prochnik

Sofia Robb

Why is it important for biologists to learn to program?

You probably already know the answer to this question since you are here.

We firmly believe that knowing how to program is just as essential as knowing how to run a gel or set up a PCR reaction. The data we now get from a single experiment can be overwhelming. This data often needs to be reformatted, filtered, and analyzed in unique ways. Programming allows you to perform these tasks in an efficient and reproducible way.

What are our tips for having a successful programming course?

-

Practice, practice, practice. Please spend as much time as possible actually coding.

-

Write only a line or two of code, then test it. If you write too many lines, it becomes more difficult to debug if there is an error.

-

Errors are not failures. Every error you get is a learning opportunity. Every single error you debug is a major success. Fixing errors is how you will cement what you have learned.

-

Don't spend too much time trying to figure out a problem. While it's a great learning experience to try to solve an issue on your own, it's not fun getting frustrated or spending a lot of time stuck. We are here to help you, so please ask us whenever you need help.

-

Lectures are important, but the practice is more important.

-

Review sessions are important, but practice is more important.

-

Our key goal is to slowly, but surely, teach you how to solve problems on your own.

Underlying the pretty Mac OSX GUI is a powerful command-line operating system. The command-line gives you access to the internals of the OS, and is also a convenient way to write custom software and scripts.

Many bioinformatics tools are written to run on the command-line and have no graphical interface. In many cases, a command-line tool is more versatile than a graphical tool, because you can easily combine command-line tools into automated scripts that accomplish tasks without human intervention.

In this course, we will be writing Python scripts that are completely command-line based.

Your workstation is an iMac. To log into it, provide the following information:

Your username: admin

Your password: cshl

To bring up the command-line, use the Finder to navigate to Applications->Utilities and double-click on the Terminal application. This will bring up a window like the following:

You can open several Terminal windows at once. This is often helpful.

You will be using this application a lot, so I suggest that you drag the Terminal icon into the shortcuts bar at the bottom of your screen.

The terminal window is running shell called "bash." The shell is a loop that:

- Prints a prompt

- Reads a line of input from the keyboard

- Parses the line into one or more commands

- Executes the commands (which usually print some output to the terminal)

- Go back 1.

There are many different shells with bizarre names like bash, sh, csh, tcsh, ksh, and zsh. The "sh" part means shell. Each shell has different and somewhat confusing features. We have set up your accounts to use bash. Stay with bash and you'll get used to it, eventually.

Most of bioinformatics is done with command-line software, so you should take some time to learn to use the shell effectively.

This is a command-line prompt:

bush202>

This is another:

(~) 51%

This is another:

srobb@bush202 1:12PM>

What you get depends on how the system administrator has customized your login. You can customize it yourself when you know how.

The prompt tells you the shell is ready to accept a command. When a long-running command is going, the prompt will not reappear until the system is ready to deal with your next request.

Type in a command and press the <Enter> key. If the command has output, it will appear on the screen. Example:

(~) 53% ls -F

GNUstep/ cool_elegans.movies.txt man/

INBOX docs/ mtv/

INBOX~ etc/ nsmail/

Mail@ games/ pcod/

News/ get_this_book.txt projects/

axhome/ jcod/ public_html/

bin/ lib/ src/

build/ linux/ tmp/

ccod/

(~) 54%

The command here is ls -F which produces a listing of files and directories in the current directory (more on that later). Below its output, the command prompt appears again.

Some programs will take a long time to run. After you issue their command names, you won't recover the shell prompt until they're done. You can either launch a new shell (from Terminal's File menu), or run the command in the background by adding an ampersand after the command

(~) 54% long_running_application &

(~) 55%

The command will now run in the background until it is finished. If it has any output, the output will be printed to the terminal window. You may wish to capture the output in a file (called redirection). We'll describe this later.

Most shells offer command-line editing. Up until the comment you press , you can go back over the command-line and edit it using the keyboard. Here are the most useful keystrokes:

- Backspace: Delete the previous character and back up one.

- Left arrow, right arrow: Move the text insertion point (cursor) one character to the left or right.

- control-a (^a): Move the cursor to the beginning of the line. (Mnemonic: A is first letter of alphabet)

- control-e (^e): Move the cursor to the end of the line. Mnemonic: E for the End (^z was already used for interrupt a command).

- control-d (^d): Delete the character currently under the cursor. D=Delete.

- control-k (^k): Delete the entire line from the cursor to the end. k=kill. The line isn't actually deleted, but put into a temporary holding place called the "kill buffer". This is like cutting text

- control-y (^y): Paste the contents of the kill buffer onto the command-line starting at the cursor. y=yank. This is like paste.

- Up arrow, down arrow: Move up and down in the command history. This lets you reissue previous commands, possibly after modifying them.

There are also some useful shell commands you can issue:

historyShow all the commands that you have issued recently, nicely numbered.!<number>Reissue an old command, based on its number (which you can get fromhistory).!!Reissue the immediate previous command.!<partial command string>: Reissue the previous command that began with the indicated letters. For example,!l(the letter el, not a number 1) would reissue thels -Fcommand from the earlier example.

bash offers automatic command completion and spelling correction. If you type part of a command and then the tab key, it will prompt you with all the possible completions of the command. For example:

(~) 51% fd<tab><tab>

(~) 51% fd

fd2ps fdesign fdformat fdlist fdmount fdmountd fdrawcmd fdumount

(~) 51%

If you hit tab after typing a command, but before pressing <Enter>, bash will prompt you with a list of file names. This is because many commands operate on files.

You can use wildcards when referring to files. * stands for zero or more characters. ? stands for any single character. For example, to list all files with the extension ".txt", run ls with the wildcard pattern "*.txt"

(~) 56% ls -F *.txt

final_exam_questions.txt genomics_problem.txt

genebridge.txt mapping_run.txt

There are several more advanced types of wildcard patterns that you can read about in the tcsh manual page. For example, if you want to match files that begin with the characters "f" or "g" and end with ".txt", you can use a range of characters inside square brackets [f-g] as part of the wildcard pattern. Here's an example

(~) 57% ls -F [f-g]*.txt

final_exam_questions.txt genebridge.txt genomics_problem.txt

When you first log in, you'll be placed in a part of the system that is your personal directory, called the home directory. You are free to do with this area what you will: in particular you can create and delete files and other directories. In general, you cannot create files elsewhere in the system.

Your home directory lives somewhere in the filesystem. On our iMacs, it is a directory with the same name as your login name, located in /Users. The full directory path is therefore /Users/username. Since this is a pain to write, the shell allows you to abbreviate it as ~username (where "username" is your user name), or simply as ~. The weird character (called "tilde" or "twiddle") is usually hidden at the upper left corner of your keyboard.

To see what is in your home directory, issue the command ls -F:

(~) % ls -F

INBOX Mail/ News/ nsmail/ public_html/

This shows one file "INBOX" and four directories ("Mail", "News") and so on. (The -F in the command turns on fancy mode, which appends special characters to directory listings to tell you more about what you're seeing. / at the end of a filename means that file is a directory.)

In addition to the files and directories shown with ls -F, there may be one or more hidden files. These are files and directories whose names start with a . (called the "dot" character). To see these hidden files, add an a to the options sent to the ls command:

(~) % ls -aF

./ .cshrc .login Mail/

../ .fetchhost .netscape/ News/

.Xauthority .fvwmrc .xinitrc* nsmail/

.Xdefaults .history .xsession@ public_html/

.bash_profile .less .xsession-errors

.bashrc .lessrc INBOX

Whoa! There's a lot of hidden stuff there. But don't go deleting dot files. Many of them are essential configuration files for commands and other programs. For example, the

.profilefile contains configuration information for the bash shell. You can peek into it and see all of bash's many options. You can edit it (when you know what you're doing) in order to change things like the command prompt and command search path.

You can move around from directory to directory using the cd command. Give the name of the directory you want to move to, or give no name to move back to your home directory. Use the pwd command to see where you are (or rely on the prompt, if configured):

(~/docs/grad_course/i) 56% cd

(~) 57% cd /

(/) 58% ls -F

bin/ dosc/ gmon.out mnt/ sbin/

boot/ etc/ home@ net/ tmp/

cdrom/ fastboot lib/ proc/ usr/

dev/ floppy/ lost+found/ root/ var/

(/) 59% cd ~/docs/

(~/docs) 60% pwd

/usr/home/lstein/docs

(~/docs) 62% cd ../projects/

(~/projects) 63% ls

Ace-browser/ bass.patch

Ace-perl/ cgi/

Foo/ cgi3/

Interface/ computertalk/

Net-Interface-0.02/ crypt-cbc.patch

Net-Interface-0.02.tar.gz fixer/

Pts/ fixer.tcsh

Pts.bak/ introspect.pl*

PubMed/ introspection.pm

SNPdb/ rhmap/

Tie-DBI/ sbox/

ace/ sbox-1.00/

atir/ sbox-1.00.tgz

bass-1.30a/ zhmapper.tar.gz

bass-1.30a.tar.gz

(~/projects) 64%

Each directory contains two special hidden directories named

.and... The first,.refers always to the current directory...refers to the parent directory. This lets you move upward in the directory hierarchy like this:

(~/docs) 64% cd ..

and to do arbitrarily weird things like this:

(~/docs) 65% cd ../../lstein/docs

The latter command moves upward two levels, and then into a directory named

docsinside a directory calledlstein.

If you get lost, the pwd command prints out the full path to the current directory:

(~) 56% pwd

/Users/lstein

With the exception of a few commands that are built directly into the shell, all Unix commands are standalone executable programs. When you type the name of a command, the shell will search through all the directories listed in the PATH environment variable for an executable of the same name. If found, the shell will execute the command. Otherwise, it will give a "command not found" error.

Most commands live in /bin, /usr/bin, or /usr/local/bin.

The man command will give a brief synopsis of a command. Let's get information about the command wc

(~) 76% man wc

Formatting page, please wait...

WC(1) WC(1)

NAME

wc - print the number of bytes, words, and lines in files

SYNOPSIS

wc [-clw] [--bytes] [--chars] [--lines] [--words] [--help]

[--version] [file...]

DESCRIPTION

This manual page documents the GNU version of wc. wc

counts the number of bytes, whitespace-separated words,

...

The apropos command will search for commands matching a keyword or phrase. Here's an example that looks for commands related to 'column'

(~) 100% apropos column

showtable (1) - Show data in nicely formatted columns

colrm (1) - remove columns from a file

column (1) - columnate lists

fix132x43 (1) - fix problems with certain (132 column) graphics

modes

Many commands take arguments. Arguments are often the names of one or more files to operate on. Most commands also take command-line "switches" or "options", which fine-tune what the command does. Some commands recognize "short switches" that consist of a minus sign - followed by a single character, while others recognize "long switches" consisting of two minus signs -- followed by a whole word.

The wc (word count) program is an example of a command that recognizes both long and short options. You can pass it the -c, -w and/or -l options to count the characters, words and lines in a text file, respectively. Or you can use the longer but more readable, --chars, --words or --lines options. Both these examples count the number of characters and lines in the text file /var/log/messages:

(~) 102% wc -c -l /var/log/messages

23 941 /var/log/messages

(~) 103% wc --chars --lines /var/log/messages

23 941 /var/log/messages

You can cluster short switches by concatenating them together, as shown in this example:

(~) 104% wc -cl /var/log/messages

23 941 /var/log/messages

Many commands will give a brief usage summary when you call them with the -h or --help switch.

The shell uses whitespace (spaces, tabs and other non-printing characters) to separate arguments. If you want to embed whitespace in an argument, put single quotes around it. For example:

mail -s 'An important message' 'Bob Ghost <bob@ghost.org>'

This will send an e-mail to the fictitious person Bob Ghost. The -s switch takes an argument, which is the subject line for the e-mail. Because the desired subject contains spaces, it has to have quotes around it. Likewise, my name and e-mail address, which contains embedded spaces, must also be quoted in this way.

Certain special non-printing characters have escape codes associated with them:

| Escape Code | Description |

|---|---|

| \n | new line character |

| \t | tab character |

| \r | carriage return character |

| \a | bell character (ding! ding!) |

| \nnn | the character whose ASCII code is nnn |

Here are some commands that are used extremely frequently. Use man to learn more about them. Some of these commands may be useful for solving the problem set ;-)

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

ls |

Directory listing. Most frequently used as ls -F (decorated listing), ls -l (long listing), ls -a (list all files). |

mv |

Rename or move a file or directory. |

cp |

Copy a file. |

rm |

Remove (delete) a file. |

mkdir |

Make a directory |

rmdir |

Remove a directory |

ln |

Create a symbolic or hard link. |

chmod |

Change the permissions of a file or directory. |

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

cat |

Concatenate program. Can be used to concatenate multiple files together into a single file, or, much more frequently, to view the contents of a file or files in the terminal. |

echo |

print a copy of some text to the screen. E.g. echo 'Hello World!' |

more |

Scroll through a file page by page. Very useful when viewing large files. Works even with files that are too big to be opened by a text editor. |

less |

A version of more with more features. |

head |

View the first few lines of a file. You can control how many lines to view. |

tail |

View the end of a file. You can control how many lines to view. You can also use tail -f to view a file that you are writing to. |

wc |

Count words, lines and/or characters in one or more files. |

tr |

Substitute one character for another. Also useful for deleting characters. |

sort |

Sort the lines in a file alphabetically or numerically. |

uniq |

Remove duplicated lines in a file. |

cut |

Remove columns from each line of a file or files. |

fold |

Wrap each input line to fit in a specified width. |

grep |

Filter a file for lines matching a specified pattern. Can also be reversed to print out lines that don't match the specified pattern. |

gzip (gunzip) |

Compress (uncompress) a file. |

tar |

Archive or unarchive an entire directory into a single file. |

emacs |

Run the Emacs text editor (good for experts). |

vi |

Run the vi text editor (better for experts). |

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

ssh |

A secure (encrypted) way to log into machines. |

scp |

A secure way to copy (cp) files to and from remote machines. |

ping |

See if a remote host is up. |

ftp/ sftp (secure) |

transfer files using the File Transfer Protocol. |

Unix commands communicate via the command-line interface. They can print information out to the terminal for you to see, and accept input from the keyboard (that is, from you!)

Every Unix program starts out with three connections to the outside world. These connections are called "streams", because they act like a stream of information (metaphorically speaking):

| Stream Type | Description |

|---|---|

| standard input | This is a communications stream initially attached to the keyboard. When the program reads from standard input, it reads whatever text you type in. |

| standard output | This stream is initially attached to the terminal. Anything the program prints to this channel appears in your terminal window. |

| standard error | This stream is also initially attached to the terminal. It is a separate channel intended for printing error messages. |

The word "initially" might lead you to think that standard input, output and error can somehow be detached from their starting places and reattached somewhere else. And you'd be right. You can attach one or more of these three streams to a file, a device, or even to another program. This sounds esoteric, but it is actually very useful.

The wc program counts lines, characters and words in data sent to its standard input. You can use it interactively like this:

(~) 62% wc

Mary had a little lamb,

little lamb,

little lamb.

Mary had a little lamb,

whose fleece was white as snow.

^D

6 20 107

In this example, I ran the wc program. It waited for me to type in a little poem. When I was done, I typed the END-OF-FILE character, control-d (^d for short). wc then printed out three numbers indicating the number of lines, words and characters in the input.

More often, you'll want to count the number of lines in a big file; say a file filled with DNA sequences. You can do this by redirecting the contents of a file to the standard input of wc. This uses

the < symbol:

(~) 63% wc < big_file.fasta

2943 2998 419272

If you wanted to record these counts for posterity, you could redirect standard output as well using the > symbol:

(~) 64% wc < big_file.fasta > count.txt

Now if you cat the file count.txt, you'll see that the data has been recorded. cat works by taking its standard input and copying it to standard output. We redirect standard input from the count.txt file, and leave standard output at its default, attached to the terminal:

(~) 65% cat < count.txt

2943 2998 419272

Here's the complete list of redirection commands for bash:

| Redirect command | Description |

|---|---|

< myfile.txt |

Redirect the contents of the file to standard input |

> myfile.txt |

Redirect standard output to file |

>> logfile.txt |

Append standard output to the end of the file |

1 > myfile.txt |

Redirect just standard output to file (same as above) |

2 > myfile.txt |

Redirect just standard error to file |

> myfile.txt 2>&1 |

Redirect both stdout and stderr to file |

These can be combined. For example, this command redirects standard input from the file named /etc/passwd, writes its results into the file search.out, and writes its error messages (if any) into a file named search.err. What does it do? It searches the password file for a user named "root" and returns all lines that refer to that user.

(~) 66% grep root < /etc/passwd > search.out 2> search.err

Many Unix commands act as filters, taking data from a file or standard input, transforming the data, and writing the results to standard output. Most filters are designed so that if they are called with one or more filenames on the command-line, they will use those files as input. Otherwise they will act on standard input. For example, these two commands are equivalent:

(~) 66% grep 'gatttgc' < big_file.fasta

(~) 67% grep 'gatttgc' big_file.fasta

Both commands use the grep command to search for the string "gatttgc" in the file big_file.fasta. The first one searches standard input, which happens to be redirected from the file. The second command is explicitly given the name of the file on the command line.

Sometimes you want a filter to act on a series of files, one of which happens to be standard input. Many commands let you use - on the command-line as an alias for standard input. Example:

(~) 68% grep 'gatttgc' big_file.fasta bigger_file.fasta -

This example searches for "gatttgc" in three places. First it looks in file big_file.fasta, then in bigger_file.fasta, and lastly in standard input (which, since it isn't redirected, will come from the keyboard).

The coolest thing about the Unix shell is its ability to chain commands together into pipelines. Here's an example:

(~) 65% grep gatttgc big_file.fasta | wc -l

22

There are two commands here. grep searches a file or standard input for lines containing a particular string. Lines which contain the string are printed to standard output. wc -l is the familiar word count program, which counts words, lines and characters in a file or standard input. The -l command-line option instructs wc to print out just the line count. The | character, which is known as a "pipe", connects the two commands together so that the standard output of grep becomes the standard input of wc. Think of pipes connecting streams of data flowing.

What does this pipe do? It prints out the number of lines in which the string "gatttgc" appears in the file big_file.fasta.

Pipes are very powerful. Here are some common command-line idioms.

Count the Number of Times a Pattern does NOT Appear in a File

The example at the top of this section showed you how to count the number of lines in which a particular string pattern appears in a file. What if you want to count the number of lines in which a pattern does not appear?

Simple. Reverse the test with the -v switch:

(~) 65% grep -v gatttgc big_file.fasta | wc -l

2921

Uniquify Lines in a File

If you have a long list of names in a text file, and you want to weed out the duplicates:

(~) 66% sort long_file.txt | uniq > unique.out

This works by sorting all the lines alphabetically and piping the result to the uniq program, which removes duplicate lines that occur one after another. That's why you need to sort first. The output is placed in a file named unique.out.

Concatenate Several Lists and Remove Duplicates

If you have several lists that might contain repeated entries among them, you can combine them into a single unique list by concatenating them together, then sorting and uniquifying them as before:

(~) 67% cat file1 file2 file3 file4 | sort | uniq

Count Unique Lines in a File

If you just want to know how many unique lines there are in the file, add a wc to the end of the pipe:

(~) 68% sort long_file.txt | uniq | wc -l

Page Through a Really Long Directory Listing

Pipe the output of ls to the more program, which shows a page at a time. If you have it, the less program is even better:

(~) 69% ls -l | more

Monitor a Growing File for a Pattern

Pipe the output of tail -f (which monitors a growing file and prints out the new lines) to grep. For example, this will monitor the /var/log/syslogfile for the appearance of e-mails addressed to 'mzhang':

(~) 70% tail -f /var/log/syslog | grep mzhang

Here are a few more advanced Unix commands that are very useful and when you have time you should investigate further. We list the page numbers in the Internet Version (v3) of 'The Linux Command Line' by William Shotts.

awksed(p.295)perlone-linersforloops (p. 453)

It is often necessary to create and write to a file while using the terminal. This makes it essential to use a terminal text editor. There are many text editors out there. Some of our favorite are Emacs and vim. We are going to start you out with a simple text editor called nano

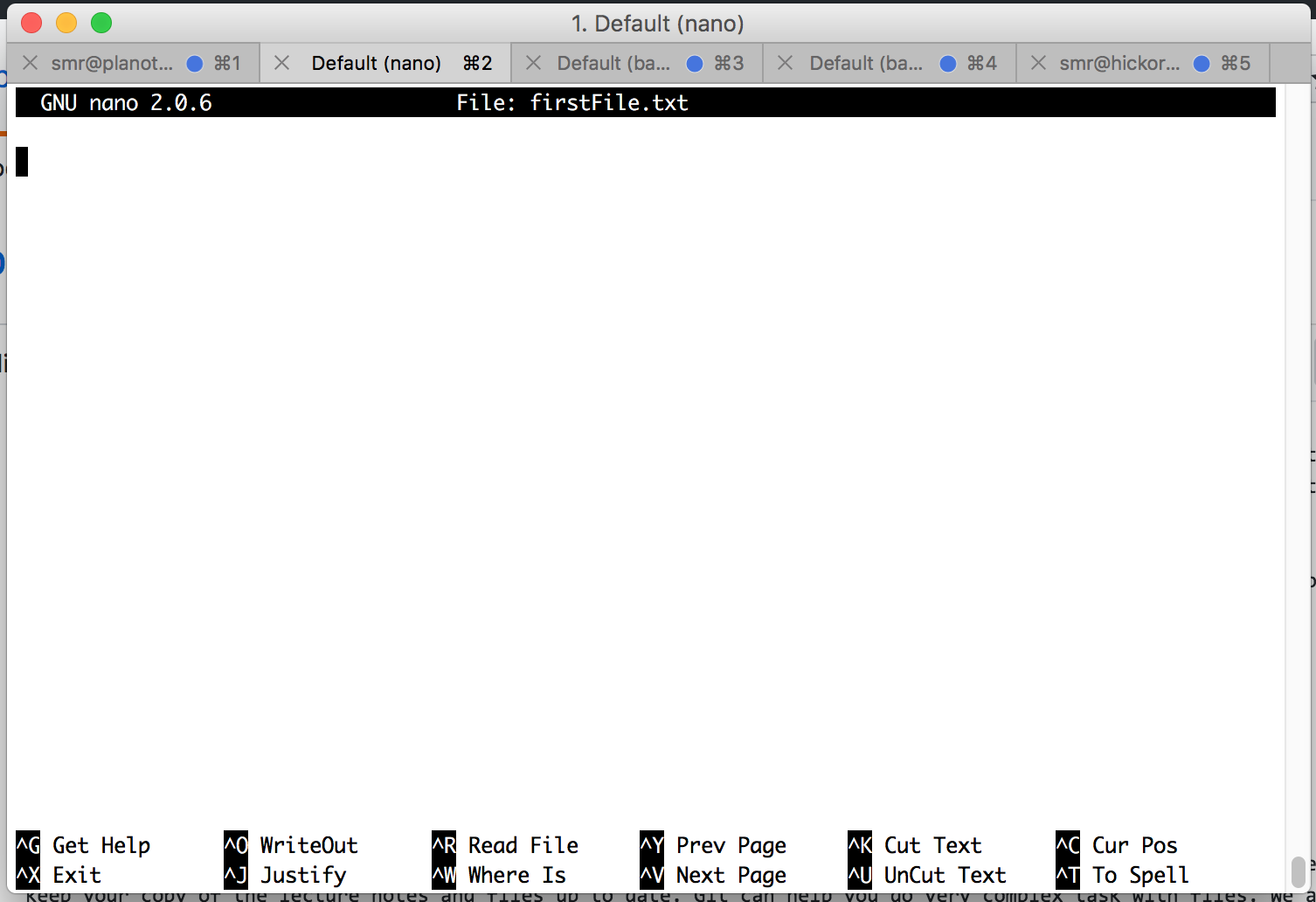

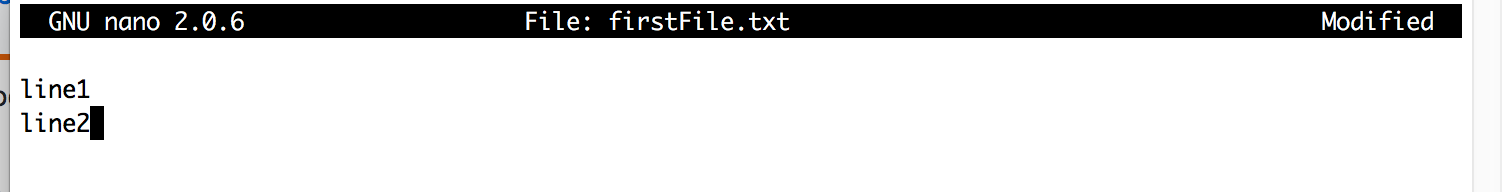

The way you use nano to create a file is simply by typing the command nano followed by the name of the file you wish to create.

(~) 71% nano firstFile.txt

This is what you will see:

Things to notice:

- At the top

- the name of the program (nano) and its version number

- the name of the file you’re editing

- and whether the file has been modified since it was last saved.

- In the middle

- you will see either a blank area or text you have typed

- At the bottom

- A listing of keyboard commands such as Save (control + o) and Exit (control + x)

Keyboard commands are the only way to interact with the editor. You cannot use your mouse or trackpad.

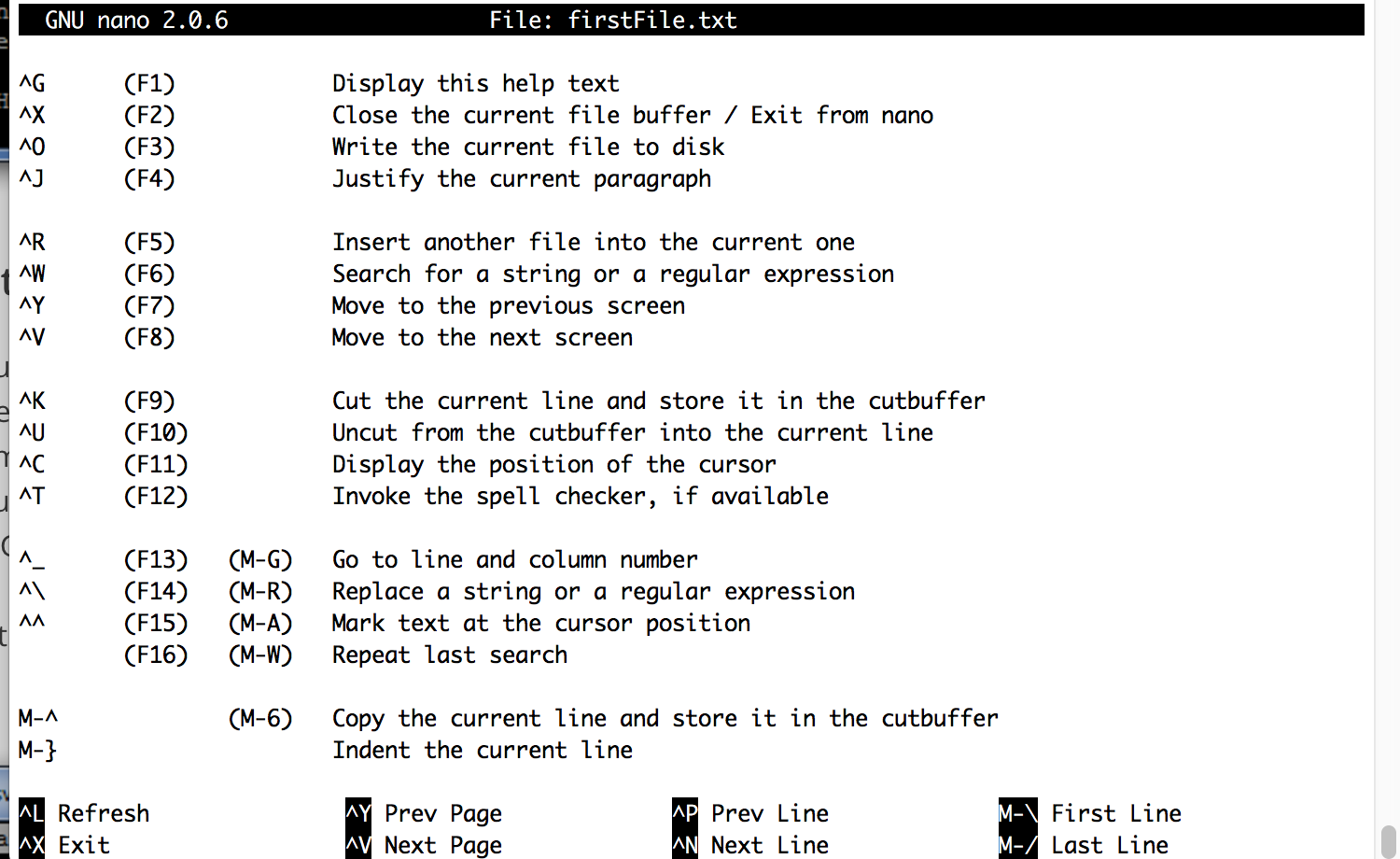

Find more commands by using control g:

The Meta key is <esc>. To use the Meta+key, hit <esc>, release, then hit the following key

Helpful commands:

- Jump to a specific line:

- control + _ then line number

- Copy a block of highlighted text

- control + ^ then move your cursor to start to highlight a block for copying

- Meta + ^ to end your highlight block

- Paste

- control + u

Nano is a beginner's text editor. vi and Emacs are better choices once you become a bit more comfortable using the terminal. These editors do cool stuff like syntax highlighting.

Git is a tool for managing files and versions of files. It is a Version Control System. It allows you to keep track of changes. You are going to be using Git to manage your course work and keep your copy of the lecture notes and files up to date. Git can help you do very complex task with files. We are going to keep it simple.

A Version Control System is good for Collaborations, Storing Versions, Restoring Previous Versions, and Managing Backups.

Using a Version Control System makes it possible to edit a document with others without the fear of overwriting someone's changes, even if more than one person is working on the same part of the document. All the changes can be merged into one document. These documents are all stored one place.

A Version Control System allows you to save versions of your files and to attach notes to each version. Each save will contain information about the lines that were added or alted.

Since you are keeping track of versions, it is possible to revert all the files in a project or just one file to a previous version.

A Version Control System makes it so that you work locally and sync your work remotely. This means you will have a copy of your project on your computer and the Version Control System Server you are using.

git is the Version Control System we will be using for tracking changes in our files.

GitHub is the Version Control System Server we will be using. They provide free account for all public projects.

A repository is a project that contains all of the project files, and stores each file's revision history. Repositories can have multiple collaborators. Repositories usually have two components, one remote and one local.

Let's Do It!

Follow Steps 1 and 2 to create the remote repository. Follow Step 3 to create your local repository and link it to the remote.

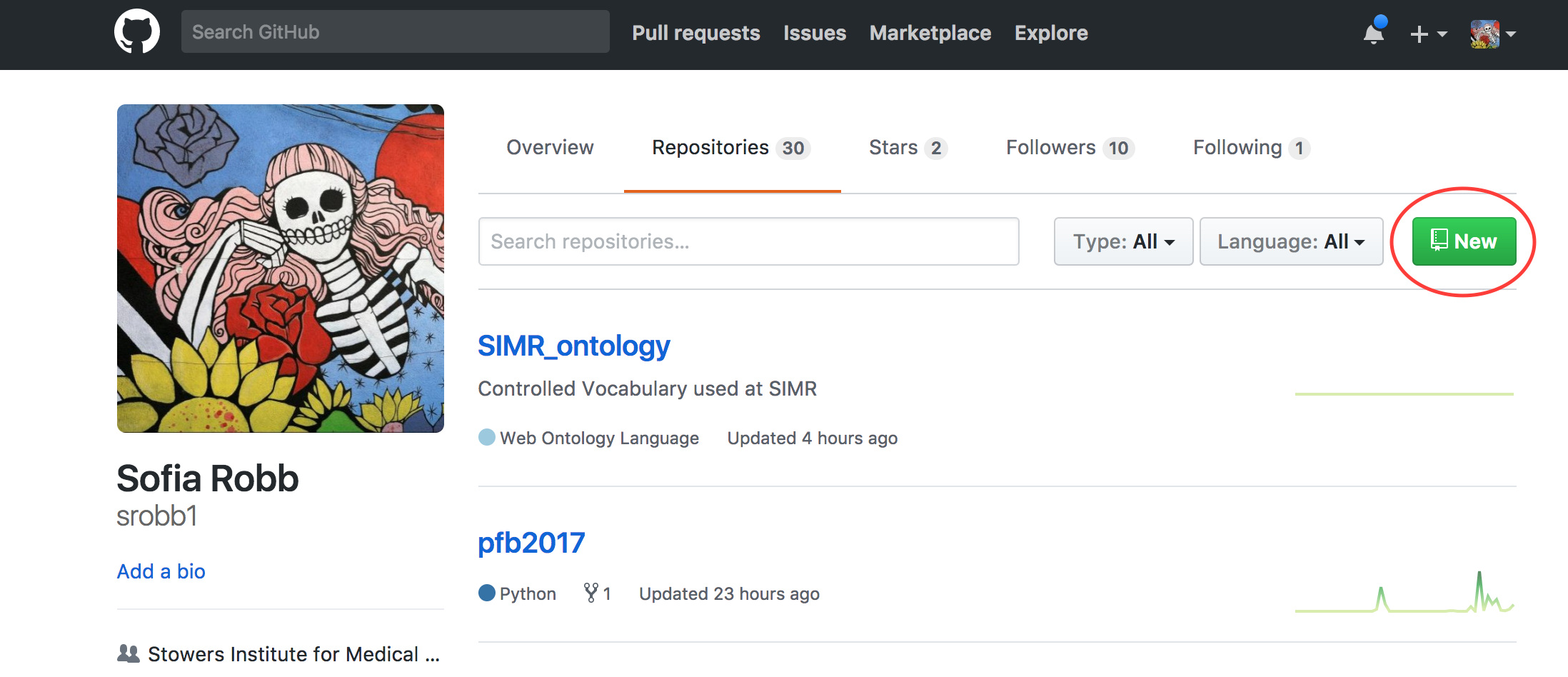

- Navigate to GitHub --> Create Account / Log In --> Go To Repositories --> Click 'New'

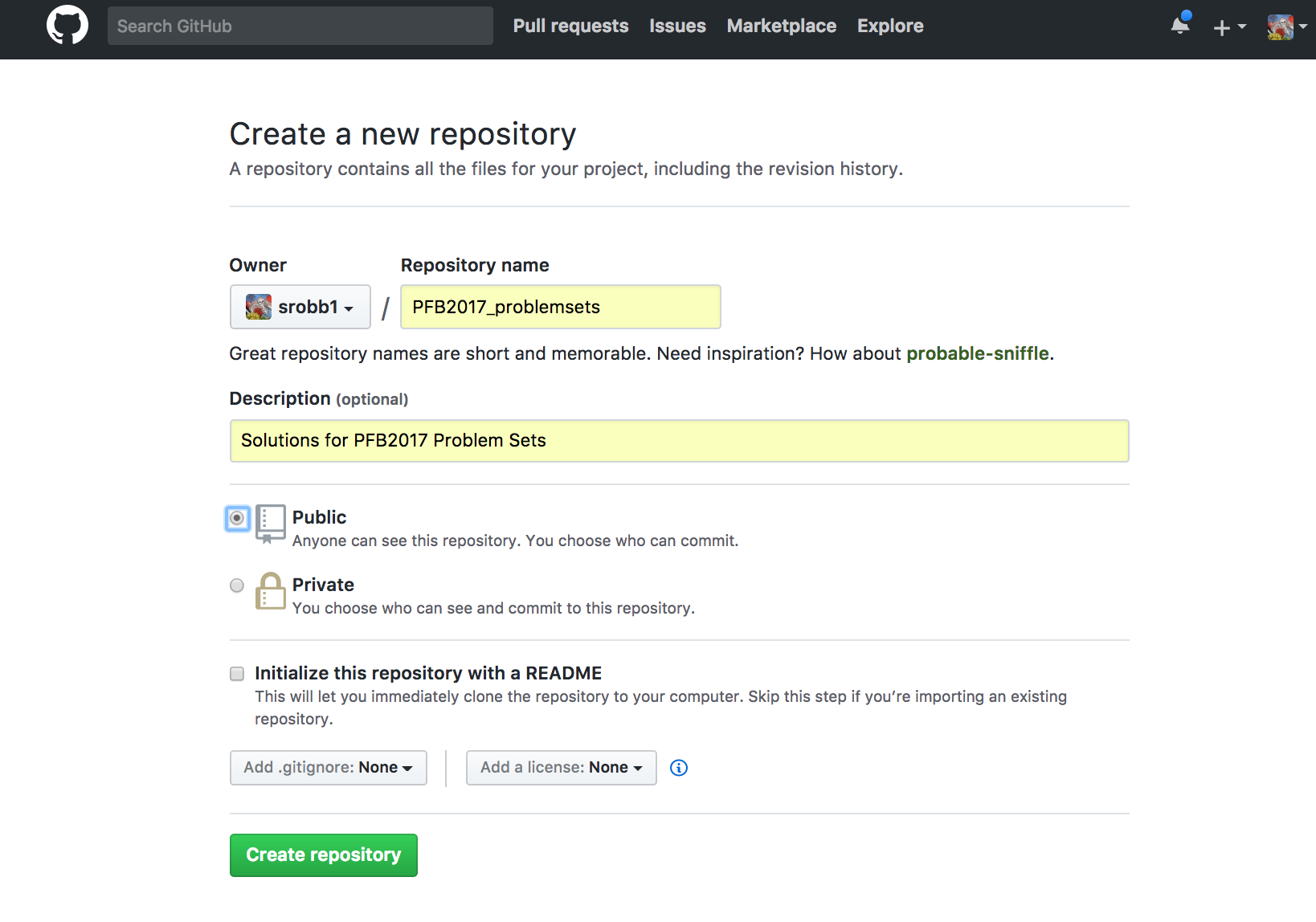

- Add a name (i.e., PFB2017_problemsets) and a description (i.e., Solutions for PFB2017 Problem Sets) and click "Create Repository"

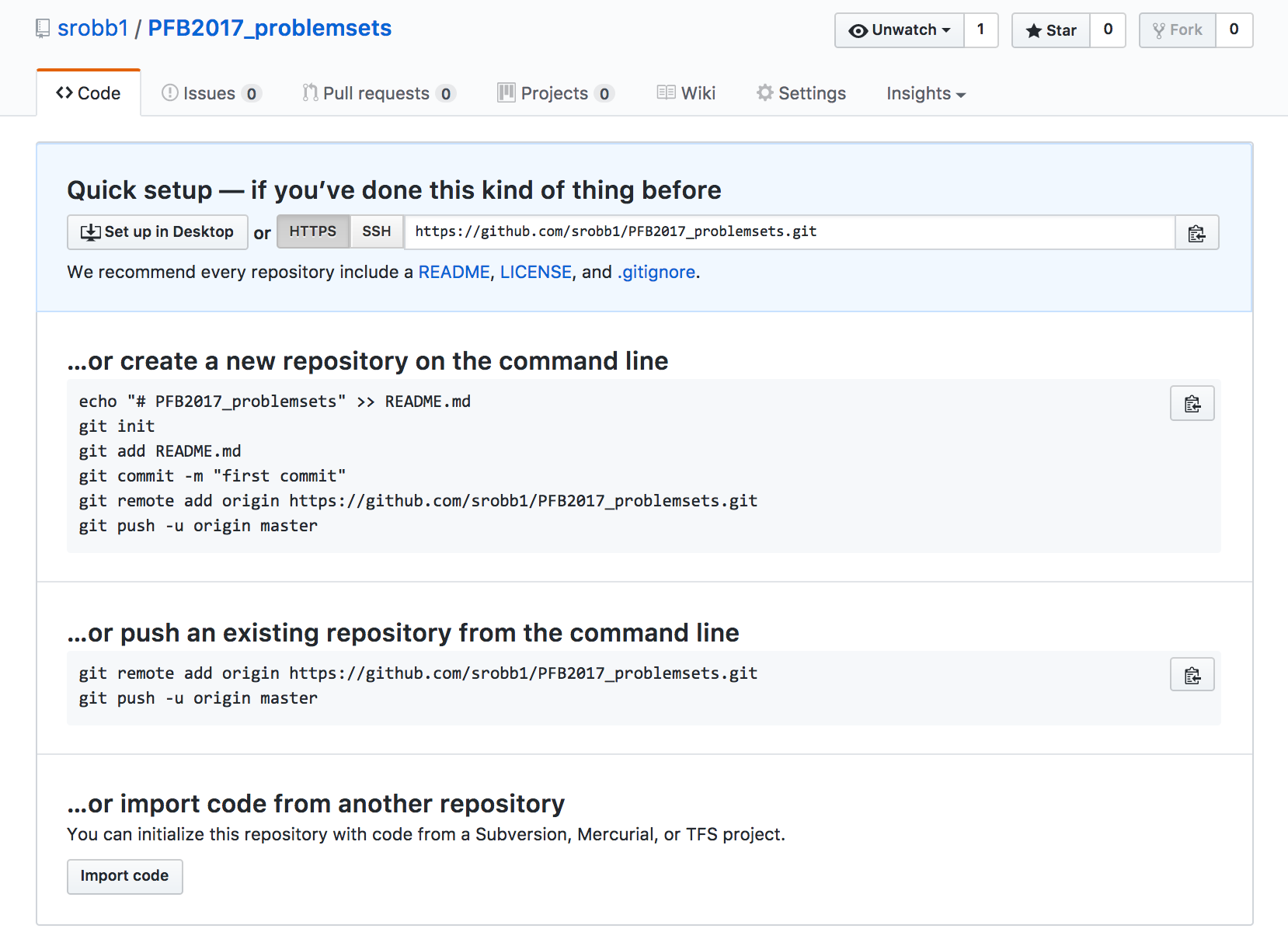

- Create a directory on your computer and follow the instructions provided.

- Open your terminal and navigate to the location you want to put a directory for your problem sets

- Create a new directory directory (i.e., PFB2017_problemsets)

- Follow the instructions provided when you created your repository. These are my instructions, yours will be different.

echo "# PFB2017_problemsets" >> README.md

git init

git add README.md

git commit -m "first commit"

git remote add origin https://github.com/prog4biol/PFB2017_problemsets.git

git push -u origin master

You now have a repository!

Let's back up a bit and talk more about git and about these commands. For basic git use, these are almost all the command you will need to know.

Every git repository has three main elements called trees:

- The Working Directory contains your files

- The Index is the staging area

- The HEAD points to the last commit you made.

There are a few new words here, we will explain them as we go

| command | description |

|---|---|

git init |

Creates your new local repository with the three trees on (local machine) |

git remote add remote-name URL |

Links your local repository to a remote repository that is often named origin and is found at the given URL. |

git add filename |

Propose changes and add file(s) with changes to the index or staging area (local machine) |

git commit -m 'message' |

Confirm or commit that you really want to add your changes to the HEAD (local machine) |

git push -u remote-name remote-branch |

Upload your committed changes in the HEAD to the specified remote repository to the specified branch |

Let's Do it!

- Make sure you are in your local repository

- Create a new file with nano:

nano git_exercises.txt - Add a line of text to the new file.

- Save (control + o) and Exit (control + x)

- (Add) Stage your changes.

git add git_exercises.txt - (Commit) Become sure you want your changes your changes.

git commit -m 'added a line of text' - (Push) Sync/Upload your changes to the remote repository.

git push origin master

That is all there is to it! There are more complicated things you can do but we won't get into those. You will know when you are ready to learn more about git when you figure out there is something you want to do but don't know how. There are thousands of online tutorials for you to search and follow.

Sometimes you want to download and use someone else's repository.

Let's clone the course material.

Let's do it!

- Go to our PFB2017 GitHub Repository

- Click the 'Clone or Download' Button

- Copy the URL ~Clone PFB2017

- Clone the repository to your local machine

git clone https://github.com/prog4biol/pfb2017.git

Now you have a copy of the course material on your computer!

If we make changes to any of these files and you want to update your copy you can pull the changes.

git pull

If you are ever wondering what do you need to add to your remote repository use the git status command. This will provide you a list of file that have been modified, deleted, and those that are untracked. Untracked files are those that have never been added to the staging area with git add

You will KNOW if you need to use these features of git.

Python is a scripting language. It is useful for writing medium-sized scientific coding projects. When you run a Python script, the Python program will generate byte code and interpret the byte code. This happens automatically and you don't have to worry about it. Compiled languages like C, C++ will run much faster, but are much much more complicated to program. Languages like java (which also gets compiled into byte code) are well suited to very large collaborative programming projects, but don't run as fast as C and are more complex that Python.

Python has

- data types

- functions

- objects

- classes

- methods

Data types are just different types of data which are discussed in more detail later. Examples of data types are integer numbers and strings of letters and numbers (text). These can be stored in variables.

Functions do something with data, such as a calculation. Some functions are already built into Python. You can create your own functions as well.

Objects are a way of grouping a set of data and functions (methods) that act on that data

Classes are a way to encapsulate (organize) variables and functions. Objects get their variables and methods from the class they belong to.

Methods are just functions that belong to a class. Objects that belong to the a class can use methods from that class.

There are two versions of Python: Python 2 and Python 3. We will be using 3. This version fixes some of the problems with Python 2 and breaks some other things. A lot of code has already been written for Python 2 (it's older), but going forwards, more and more new code development will use Python 3.

Python can be run one line at a time in an interactive interpreter. You can think of this as a Python shell. To launch the interpreter type the following into your terminal window:

$ python3

Note: '$' indicates the command line prompt. Recall from Unix 1 that every computer can have a different prompt!

First Python Commands:

>>> print("Hello, PFB2017!")

Hello, PFB2017!Note:

print()

- The same code from above is typed into a text file using a text editor.

- Python scripts are always saved in files whose names have the extension '.py' (i.e. the filename ends with '.py').

File Contents:

print ("Hello, PFB2017!")Typing the Python command followed by the name of a script makes Python execute the script. Recall that we just saw you can run an interactive interpreter by just typing python on the command line

Execute the Python script like this (% represents the prompt)

% python3 test.py This produces the following result:

Hello, PFB2017!If you make your script executable, you can run it without typing python3 first. Use chmod to change the permissions on the script like this

chmod +x test.py

You can look at the permissions with

% ls -l test.py

-rwxr-xr-x 1 sprochnik staff 60 Oct 16 14:29 test.py

The first field of -, r, w and x characters define the permissions of the file. The three 'x' characters means anyone can execute or run this script.

We also need to add a line at the beginning of the script that tells the shell to run python3 to interpret the script. This line starts with #, so it looks like a comment to python. The '!' is important as is the space between env and python3. The program /usr/bin/env looks for where python3 is installed and runs the script with python3. The details may seem a bit complex, but you can just copy and paste this 'magic' line.

The file test.py now looks like this

#!/usr/bin/env python3

print ("Hello, PFB2017!")Now you can simply type the name of the script to run it. Like this

% ./test.py

Hello, PFB2017!

A Python identifier is a name used to identify a variable, function, class, module or other object. An identifier starts with a letter A to Z or a to z or an underscore (_) followed by zero or more letters, underscores and digits (0 to 9).

Python does not allow punctuation characters such as @, $, and % within identifiers. Python is a case sensitive programming language. Thus, seq_id and seq_ID are two different identifiers in Python.

- The first character is lowercase, unless it is a name of a class. Classes should begin with an uppercase characters. (ex. Seq)

- Private identifiers begin with an underscore. (ex.

_private) - Strong private identifiers begin with two underscores. (ex.

__private) - Language-defined special names begin and end with two underscores. (ex.

__special__)

The following is a list of Python keywords. These are special words that already have a purpose in python and therefore cannot be used as identifier names.

and exec not

as finally or

assert for pass

break from print

class global raise

continue if return

def import try

del in while

elif is with

else lambda yield

except

Python denotes blocks of code by line indentation. Incorrect line spacing and/or indention will cause an error or could make your code run in a way you don't expect. You can get help with indentation from good text editors or Interactive Development Environments (IDEs).

The number of spaces in the indentation need to be consistent but a specific number is not required. All lines of code, or statements, within a single block must be indented in the same way. For example:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

for x in (1,2,3,4,5):

if x > 4:

print("Hello")

else:

print(x)

print('All Done!')Comments are an essential programming practice. Making a note of what a line or block of code is doing will help the writer and readers of the code. This includes you!

Comments start with a pound or hash symbol #. All characters after this symbol, up to the end of the line are part of the comment and are ignored by Python.

The first line of a script starting with #! is a special example of a comment that also has the special function in unix of telling the unix shell how to run the script.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# this is my first script

print ("Hello, PFB2017!") # this line prints output to the screenBlank lines are also important for increasing the readability of the code. You should separate pieces of code that go together with a blank line to make 'paragraphs' of code. Blank lines are ignored by the Python interpretor.

This is our first look at variables and data types. Each data type will be discussed in more detail in subsequent sections.

The first concept to consider is that Python data types are either immutable (unchangeable) or not. Literal numbers, strings and tuples cannot be changed. Lists, dictionaries and sets can be changed. So can individual (scalar) variables. You can store data in memory by putting it in different kinds variables. You use the = sign to assign a value to a variable.

Numbers and strings are two common data types. Literal numbers and strings like this 5 or 'my name is' are immutable. However, their values can be stored in variables and then changed.

For Example:

gene_count = 5

gene_count = 10You should give your variables names that help you understand what they store. gene_count, expression, sequences are all good identifiers or variable names. k, x, data, var1, var2 are bad because you can't tell what they store. This means it's harder to understand the script and to spot errors or bugs in your script.

Different types of data can be assigned to variables, i.e., integers (1,2,3), floats (floating point numbers, 3.1415), and strings (text).

For Example:

count = 10 # this is an integer

average = 2.5 # this is a float

message = "Welcome to Python" # this is a string10, 2.5, and "Welcome to Python" are singular pieces of data being stored in an individual variables.

Collections of data can also be stored in special data types, i.e., tuples, lists, sets, and dictionaries. Generally, you should try to store like with like, so each element in the data type should be the same kind of data, like an expression value from RNA-seq or a count of how many exons are in a gene or a read sequence.

- Tuples are similar to lists and contain ordered, indexed collection of data.

- Tuples are immutable: you can't change the values or the number of values

- A tuple is enclosed in parentheses and items are separated by commas.

( 'Jan' , 'Feb' , 'Mar' , 'Apr' , 'May' , 'Jun' , 'Jul' , 'Aug' , 'Sep' , 'Oct' , 'Nov' , 'Dec' )| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 | Jan |

| 1 | Feb |

| 2 | Mar |

| 3 | Apr |

| 4 | May |

| 5 | Jun |

| 6 | Jul |

| 7 | Aug |

| 8 | Sep |

| 9 | Oct |

| 10 | Nov |

| 11 | Dec |

-

Dictionaries are good for storing data that can be represented as a two-column table.

-

They store unordered collections of key/value pairs.

-

A dictionary is enclosed in curly braces. and sets of Key/Value pairs are separated by commas

-

A colon is written between each key and value. Commas separate key:value pairs.

{ 'TP53' : 'GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC' , 'BRCA1' : 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA' }| Key | Value |

|---|---|

| TP53 | GATGGGATTGGGGTTTTCCCCTCCCATGTGCTCAAGACTGGCGCTAAAAGTTTTGAGCTTCTCAAAAGTC |

| BRCA1 | GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA |

- Lists are used to store an ordered, indexed collection of data.

- Lists are mutable: the number of elements in the list and what's stored in each element can change

- Lists are enclosed in square brackets and items are separated by commas

[ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 | atg |

| 1 | aaa |

| 2 | agg |

The list index starts at 0

Command line parameters follow the name of a script or program and have spaces between them. They allow a user to pass information to a script on the command line when that script is being run. Python stores all the pieces of the command line in a special list called sys.argv.

You need to import the sys module at the beginning of your script like this

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sysLet's imagine we have a script called friends.py. If you write this on the command line:

$ friends.py Joe AnitaThis happens inside the script:

the script name 'friends.py', and the strings 'Joe' and 'Anita' appear in a list called

sys.argv.

These are the command line parameters, or arguments you want to pass to your script.

sys.argv[0]is the script name.

You can access values of the other parameters by their indices, starting with 1, sosys.argv[1]contains 'Joe' andsys.argv[2]contains 'Anita'. You access elements in a list by adding square brackets and the numerical index after the name of the list. If you wanted to print a message saying these two people are friends, you might write some code like this

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys

friend1 = sys.argv[1] # get first command line parameter

friend2 = sys.argv[2] # get second command line parameter

# now print a message to the screen

print(friend1,'and',friend2,'are friends')The advantage of getting input from the user from the command line is that you can write a script that is general. It can print a message with any input the user provides. This makes it flexible. The user also supplies all the data the script needs on the command line so the script doesn't have to ask the user to input a name and wait til the user does this. The script can run on its own with no further interaction from the user. This frees the user to work on something else. Very handy!

You have an identifier in your code called data. Does it represent a string or a list or a dictionary? Python has a couple of functions that help you figure this out.

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

type(data) |

tells you which class your object belongs to |

dir(data) |

tells you which methods are available for your object |

id(data) |

tells you the unique object id |

We'll cover dir() in more detail later

>>> data = [2,4,6]

>>> type(data)

<class 'list'>

>>> data = 5

>>> type(data)

<class 'int'>An operator in a programming language is a symbol that tells the compiler or interpreter to perform specific mathematical, relational or logical operation and produce a result. Here we explain the concept of operators.

In Python we can write statements that perform mathematical calculations. To do this we need to use operators that are specific for this purpose. Here are arithmetic operators:

| Operator | Description | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

+ |

Addition | 3+2 |

5 |

- |

Subtraction | 3-2 |

1 |

* |

Multiplication | 3*2 |

6 |

/ |

Division | 3/2 |

1.5 |

% |

Modulus (divides left operand by right operand and returns the remainder) | 3%2 |

1 |

** |

Exponent | 3**2 |

9 |

// |

Floor Division (result is the quotient with digits after the decimal point removed. If one of the operands is negative, the result is floored, i.e., rounded away from zero | 3//2 ; -11//3 |

1 ; -4 |

We use assignment operators to assign values to variables. You have been using the = assignment operator. Here are others:

| Operator | Equivalent to | Example | result evaluates to |

|---|---|---|---|

= |

a = 3 |

result = 3 |

3 |

+= |

result = result + 2 |

result = 3 ; result += 2 |

5 |

-= |

result = result - 2 |

result = 3 ; result -= 2 |

1 |

*= |

result = result * 2 |

result = 3 ; result *= 2 |

6 |

/= |

result = result / 2 |

result = 3 ; result /= 2 |

1.5 |

%= |

result = result % 2 |

result = 3 ; result %= 2 |

1 |

**= |

result = result ** 2 |

result = 3 ; result **= 2 |

9 |

//= |

result = result // 2 |

result = 3 ; result //= 3 |

1 |

These operators compare two values and returns true or false.

| Operator | Description | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

== |

equal to | 3 == 2 |

False |

!= |

not equal | 3 != 2 |

True |

> |

greater than | 3 > 2 |

True |

< |

less than | 3 < 2 |

False |

>= |

greater than or equal | 3 >= 2 |

True |

<= |

less than or equal | 3 <= 2 |

False |

Logical operators allow you to combine two or more sets of comparisons. You can combine the results in different ways. For example you can 1) demand that all the statements are true, 2) that only one statement needs to be true, or 3) that the statement needs to be false.

| Operator | Description | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

and |

True if left operand is True and right operand is True | 3>=2 and 2<3 |

True |

or |

True if left operand is True or right operand is True | 3==2 or 2<3 |

True |

not |

Reverses the logical status | not False |

True |

You can test to see if a value is included in a string, tuple, or list. You can also test that the value is not included in the string, tuple, or list.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

in |

True if a value is included in a list, tuple, or string |

not in |

True if a value is absent in a list, tuple, or string |

For Example:

>>> dna = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

>>> 'TCT' in dna

True

>>>

>>> 'ATG' in dna

False

>>> 'ATG' not in dna

True

>>> codons = [ 'atg' , 'aaa' , 'agg' ]

>>> 'atg' in codons

True

>>> 'ttt' in codons

FalseOperators are listed in order of precedence. Highest listed first. Not all the operators listed here are mentioned above.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

** |

Exponentiation (raise to the power) |

~ + - |

Complement, unary plus and minus (method names for the last two are +@ and -@) |

* / % // |

Multiply, divide, modulo and floor division |

+ - |

Addition and subtraction |

>> << |

Right and left bitwise shift |

& |

Bitwise 'AND' |

^ | |

Bitwise exclusive 'OR' and regular 'OR' |

<= < > >= |

Comparison operators |

<> == != |

Equality operators |

= %= /= //= -= += *= **= |

Assignment operators |

is |

Identity operator |

is not |

Non-identity operator |

in |

Membership operator |

not in |

Negative membership operator |

not or and |

logical operators |

Note: Find out more about bitwise operators. We will see these operators used in the section on Sets.

Lets take a step back, What is truth?

Everything is true, except for:

| expression | TRUE/FALSE |

|---|---|

0 |

FALSE |

None |

FALSE |

False |

FALSE |

'' (empty string) |

FALSE |

[] (empty list) |

FALSE |

() (empty tuple) |

FALSE |

{} (empty dictionary) |

FALSE |

Which means that these are True:

| expression | TRUE/FALSE |

|---|---|

'0' |

TRUE |

'None' |

TRUE |

'False' |

TRUE |

'True' |

TRUE |

' ' (string of one blank space) |

TRUE |

bool() is a function that will test if a value is true.

>>> bool(True)

True

>>> bool('True')

True

>>>

>>>

>>> bool(False)

False

>>> bool('False')

True

>>>

>>>

>>> bool(0)

False

>>> bool('0')

True

>>>

>>>

>>> bool('')

False

>>> bool(' ')

True

>>>

>>>

>>> bool(())

False

>>> bool([])

False

>>> bool({})

FalseControl Statements are used to direct the flow of your code and create the opportunity for decision making. Control statements foundation is build on truth.

- Use the

ifStatement to test for truth and to execute lines of code if true. - When the expression evaluates to true each of the statements indented below the

ifstatment, also known as the nested statement block, will be executed.

if

if expression :

statement

statementFor Example:

dna = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

if 'AGC' in dna:

print('found AGC in your dna sequence')Returns:

found AGC in your dna sequence

else

- The

ifportion of the if/else statement behave as before. - The first indented block is executed if the condition is true.

- If the condition is false, the second indented else block is executed.

dna = 'GTACCTTGATTTCGTATTCTGAGAGGCTGCTGCTTAGCGGTAGCCCCTTGGTTTCCGTGGCAACGGAAAA'

if 'ATG' in dna:

print('found ATG in your dna sequence')

else:

print('did not find ATG in your dna sequence')Returns:

did not find ATG in your dna sequence

- The if condition is tested as before and the indented block is executed if the condition is true.

- If it's false, the indented block following the elif is executed if the first elif condition is true.

- Any remaining elif conditions will be tested in order until one is found to be true. If none is true, the else indented block is executed.

count = 60

if count < 0:

message = "is less than 0"

print(count, message)

elif count < 50:

message = "is less than 50"

print (count, message)

elif count > 50:

message = "is greater than 50"

print (count, message)

else:

message = "must be 50"

print(count, message)Returns:

60 is greater than 50

Let's change count to 20, which statement block gets executed?

count = 20

if count < 0:

message = "is less than 0"

print(count, message)

elif count < 50:

message = "is less than 50"

print (count, message)

elif count > 50:

message = "is greater than 50"

print (count, message)

else:

message = "must be 50"

print(count, message)Returns:

20 is less than 100

What happens when count is 50?

count = 50

if count < 0:

message = "is less than 0"

print(count, message)

elif count < 50:

message = "is less than 50"

print (count, message)

elif count > 50:

message = "is greater than 50"

print (count, message)

else:

message = "must be 50"

print(count, message)Returns:

50 must be 50

Python recognizes 3 types of numbers: integers, floating point numbers, and complex numbers.

- known as an int

- an int can be positive or negative

- and does not contain a decimal point or exponent.

- known as a float

- a floating point number can be positive or negative

- and does contain a decimal point (

4.875) or exponent (4.2e-12)

- known as complex

- is in the form of a+bi where bi is the imaginary part.

Sometimes one type of number needs to be changed to another for a function to be able to do work on it. Here are a list of functions for converting number types:

| function | Description |

|---|---|

int(x) |

to convert x to a plain integer |

float(x) |

to convert x to a floating-point number |

complex(x) |

to convert x to a complex number with real part x and imaginary part zero |

complex(x, y) |

to convert x and y to a complex number with real part x and imaginary part y |

>>> int(2.3)

2

>>> float(2)

2.0

>>> complex(2.3)

(2.3+0j)

>>> complex(2.3,2)

(2.3+2j)Here are a list of functions that take numbers as arguments. These use useful things like rounding.

| function | Description |

|---|---|

abs(x) |

The absolute value of x: the (positive) distance between x and zero. |

round(x [,n]) |

x rounded to n digits from the decimal point. round() rounds to an even integer if the value is exactly between two integers, so round(0.5) is 0 and round(-0.5) is 0. round(1.5) is 2. Rounding to a fixed number of decimal places can give unpredictable results. |

max(x1, x2,...) |

The largest positive argument is returned |

min(x1, x2,...) |

The smallest argument is returned |

>>> abs(2.3)

2.3

>>> abs(-2.9)

2.9

>>> round(2.3)

2

>>> round(2.5)

2

>>> round(2.9)

3

>>> round(-2.9)

-3

>>> round(-2.3)

-2

>>> round(-2.009,2)

-2.01

>>> round(2.675, 2) # note this rounds down

2.67

>>> max(4,-5,5,1,11)

11

>>> min(4,-5,5,1,11)

-5Many numeric functions are not built into the Python core and need to be included in our script if we want to use them. To include them at the tip of the script type:

import math

These next functions are found in the math module and need to be imported. To use these functions, prepend the function with the module name, i.e, math.ceil(15.5)

| math.function | Description |

|---|---|

math.ceil(x) |

return the smallest integer greater than or equal to x is returned |

math.floor(x) |

return the largest integer less than or equal to x. |

math.exp(x) |

The exponential of x: ex is returned |

math.log(x) |

the natural logarithm of x, for x > 0 is returned |

math.log10(x) |

The base-10 logarithm of x for x > 0 is returned |

math.modf(x) |

The fractional and integer parts of x are returned in a two-item tuple. |

math.pow(x, y) |

The value of x raised to the power y is returned |

math.sqrt(x) |

Return the square root of x for x >= 0 |

>>> import math

>>>

>>> math.ceil(2.3)

3

>>> math.ceil(2.9)

3

>>> math.ceil(-2.9)

-2

>>> math.floor(2.3)

2

>>> math.floor(2.9)

2

>>> math.floor(-2.9)

-3

>>> math.exp(2.3)

9.974182454814718

>>> math.exp(2.9)

18.17414536944306

>>> math.exp(-2.9)

0.05502322005640723

>>>

>>> math.log(2.3)

0.8329091229351039

>>> math.log(2.9)

1.0647107369924282

>>> math.log(-2.9)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: math domain error

>>>

>>> math.log10(2.3)

0.36172783601759284

>>> math.log10(2.9)

0.4623979978989561

>>>

>>> math.modf(2.3)

(0.2999999999999998, 2.0)

>>>

>>> math.pow(2.3,1)

2.3

>>> math.pow(2.3,2)

5.289999999999999

>>> math.pow(-2.3,2)

5.289999999999999

>>> math.pow(2.3,-2)

0.18903591682419663

>>>

>>> math.sqrt(25)

5.0

>>> math.sqrt(2.3)

1.51657508881031

>>> math.sqrt(2.9)

1.70293863659264Often times it is necessary to compare two numbers and find out if the first number is less than, equal to, or greater than the second.

The simple function cmp(x,y) is not available in Python 3.

Use this idiom instead:

cmp = (x>y)-(x<y)It returns three different values depending on x and y

-

if x<y -1 is returned

-

if x>y 1 is returned

-

x == y 0 is returned

In the next section, we will learn about strings, tuples and lists. These are all examples of python sequences. A string is a sequence of characters 'ACGTGA', a tuple (0.23, 9.74, -8.17, 3.24, 0.16) and a list ['dog', 'cat', 'bird'] are sequences of any kind of data. We'll see much more detail in a bit.

In Python a type of object gets operations that belong to that type. Sequences have sequence operations so strings can also use sequence operations. Strings also have their own specific operations.

You can ask what the length of any sequence is

>>>len('ACGTGA') # length of a string

6

>>>len( (0.23, 9.74, -8.17, 3.24, 0.16) ) # length of a tuple, needs two parentheses (( ))

5

>>>len(['dog', 'cat', 'bird']) # length of a list

3You can also use string-specific functions on strings, but not on lists and vice versa. We'll learn a lot more about this later on. rstrip() is a string method or function. You get an error if you try to use it on a list.

>>> 'ACGTGA'.rstrip('A')

'ACGTG'

>>> ['dog', 'cat', 'bird'].rstrip()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'rstrip'How do you find out what functions work with an object? There's a handy function dir(). As an example what functions can you call on our string 'ACGTGA'?

>>> dir('ACGTGA')

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__getnewargs__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mod__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__rmod__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'capitalize', 'casefold', 'center', 'count', 'encode', 'endswith', 'expandtabs', 'find', 'format', 'format_map', 'index', 'isalnum', 'isalpha', 'isdecimal', 'isdigit', 'isidentifier', 'islower', 'isnumeric', 'isprintable', 'isspace', 'istitle', 'isupper', 'join', 'ljust', 'lower', 'lstrip', 'maketrans', 'partition', 'replace', 'rfind', 'rindex', 'rjust', 'rpartition', 'rsplit', 'rstrip', 'split', 'splitlines', 'startswith', 'strip', 'swapcase', 'title', 'translate', 'upper', 'zfill']dir() will return all atributes of an object, among them its functions. Technically, functions belonging to a specific object are called methods.

You can call dir() on any object, most often, you'll use it in the interactive Python shell.

- A string is a series of characters starting and ending with single or double quotation marks.

- Strings are an example of a Python sequence. A sequence is defined as a positionally ordered set. This means each element in the set has a position, starting with zero, i.e. 0,1,2,3 and so on until you get to the end of the string.

- Single (')

- Double (")

- Triple (''' or """)

Notes about quotes:

- Single and double quotes are equivalent.

- A variable name inside quotes is just the string identifier, not the value stored inside the variable.

- Triple quotes are used before and after a string that spans multiple lines.

Use of quotation examples:

word = 'word'

sentence = "This is a sentence."

paragraph = """This is a paragraph. It is

made up of multiple lines and sentences. And goes

on and on.

"""We saw examples of print() earlier. Lets talk about it a bit more. print() is a function that takes one or more comma-separated arguments.

Let's use the print() function to print a string.

>>>print("ATG")

ATGLet's assign a string to a variable and print the variable.

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print(dna)

ATGWhat happens if we put the variable in quotes?

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print("dna")

dnaThe literal string 'dna' is printed to the screen, not the contents 'ATG'

Let's see what happens when we give print() two literal strings as arguments.

>>> print("ATG","GGTCTAC")

ATG GGTCTACWe get the two literal strings printed to the screen separated by a space

What if you do not want your strings separated by a space? Use the concatenation operator to concatenate the two strings before or within the print() function.

>>> print("ATG"+"GGTCTAC")

ATGGGTCTAC

>>> combined_string = "ATG"+"GGTCTAC"

ATGGGTCTAC

>>> print(combined_string)

ATGGGTCTACWe get the two strings printed to the screen without being separated by a space.

You can also use this

>>> print('ATG','GGTCTAC',sep='')

ATGGGTCTACNow, lets print a variable and a literal string.

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print(dna,'GGTCTAC')

ATG GGTCTACWe get the value of the variable and the literal string printed to the screen separated by a space

How would we print the two without a space?

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print(dna + 'GGTCTAC')

ATGGGTCTACSomething to think about: Values of variables are variable. Or in other words, they are mutable, changeable.

>>>dna = 'ATG'

ATG

>>> print(dna)

ATG

>>>dna = 'TTT'

TTT

>>> print(dna)

TTTThe new value of the variable 'dna' is printed to the screen when

dnais an argument for theprint()function.

Let's look at the typical errors you will encounter when you use the print() function.

What will happen if you forget to close your quotes?

>>> print("GGTCTAC)

File "<stdin>", line 1

print("GGTCTAC)

^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literalWe get a 'SyntaxError' if the closing quote is not used

What will happen if you forget to enclose a string you want to print in quotes?

>>> print(GGTCTAC)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'GGTCTAC' is not defined

>>> GGTCTAC = 5 # define a variable

>>> print(GGTCTAC)

5We get a 'NameError' when the literal string is not enclosed in quotes because Python is looking for a variable with the name GGTCTAC

>>> print "boo"

File "<stdin>", line 1

print "boo"

^

SyntaxError: Missing parentheses in call to 'print'In python2, the command was print, but this changed to print() in python3, so don't forget the parentheses!

How would you include a new line, carriage return, or tab in your string?

| Escape Character | Description |

|---|---|

| \n | New line |

| \r | Carriage Return |

| \t | Tab |

Let's include some escape characters in our strings and print() functions.

>>> string_with_newline = 'this sting has a new line\nthis is the second line'

>>> print(string_with_newline)

this sting has a new line

this is the second lineWe printed a new line to the screen

print() adds spaces between arguments and a new line at the end for you. You can change these with sep= and end=. Here's an example:

print('one line', 'second line' , 'third line', sep='\n', end = '')

A neater way to do this is to express a multi-line string enclosed in triple quotes (""").

>>> print("""this string has a new line

... this is the second line""")

this string has a new line

this is the second lineLet's print a tab character (\t).

>>> line = "value1\tvalue2\tvalue3"

>>> print(line)

value1 value2 value3We get the three words separated by tab characters. A common format for data is to separate columns with tabs like this.

You can add a backslash before any character to force it to be printed as a literal. This is called 'escaping'. This is only really useful for printing literal quotes ' and "

>>> print('this is a \'word\'') # if you want to print a ' inside '...'

this is a 'word'

>>> print("this is a 'word'") # maybe clearer to print a ' inside "..."

this is a 'word'In both cases actual single quote character are printed to the screen

If you want every character in your string to remain exactly as it is, declare your string a raw string literal with 'r' before the first quote. This looks ugly, but it works.

>>> line = r"value1\tvalue2\tvalue3"

>>> print(line)

value1\tvalue2\tvalue3Our escape characters '\t' remain as we typed them, they are not converted to actual tab characters.

To concatenate strings use the concatenation operator '+'

>>> promoter= 'TATAAA'

>>> upstream = 'TAGCTA'

>>> downstream = 'ATCATAAT'

>>> dna = upstream + promoter + downstream

>>> print(dna)

TAGCTATATAAAATCATAATThe concatenation operator can be used to combine strings. The newly combined string can be stored in a variable.

What happens if you use + with numbers (these are integers or ints)?

>>> 4+3

7For strings, + concatenates; for integers, + adds.

You need to convert the numbers to strings before you can concatenate them

>>> str(4) + str(3)

'43'Use the len() function to calculate the length of a string. This function takes a sequence as an argument and returns an int

>>> print(dna)

TAGCTATATAAAATCATAAT

>>> len(dna)

20The length of the string, including spaces, is calculated and returned.

The value that len() returns can be stored in a variable.

>>> dna_length = len(dna)

>>> print(dna_length)

20You can mix strings and ints in print(), but not in concatenation.

>>> print("The lenth of the DNA sequence:" , dna , "is" , dna_length)

The lenth of the DNA sequence: TAGCTATATAAAATCATAAT is 20Changing the case of a string is a bit different than you might first expect. For example, to lowercase a string we need to use a method. A method is a function that is specific to an object. When we assign a string to a variable we are creating an instance of a string object. This object has a series of methods that will work on the data that is stored in the object. Recall that dir() will tell you all the methods that are available for an object. The lower() function is a string method.

Let's create a new string object.

dna = "ATGCTTG"Look familiar? It should!!! Creating a string object is what we have been doing all along!!! Jeez!!!

Now that we have a string object we can use string methods. The way you use a method is to put a '.' between the object and the method name.

>>> dna = "ATGCTTG"

>>> dna.lower()

'atgcttg'the lower() method returns the contents stored in the 'dna' variable in lowercase.

The contents of the 'dna' variable have not been changed. Strings are immutable. If you want to keep the lowercased version of the string, store it in a new variable.

>>> print(dna)

ATGCTTG

>>> dna_lowercase = dna.lower()

>>> print(dna)

ATGCTTG

>>> print(dna_lowercase)

atgcttgThe string method can be nested inside of other functions.

>>> dna = "ATGCTTG"

>>> print(dna.lower())

atgcttgThe contents of 'dna' are lowercased and passed to the

print()function.

If you try to use a string method on a object that is not a string you will get an error.

>>> nt_count = 6

>>> dna_lc = nt_count.lower()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'int' object has no attribute 'lower'You get an AttributeError when you use a method on the an incorrect object type. We are told that the int object (an int is returned by

len()) does not have a function called lower.

Now let's uppercase a string.

>>> dna = 'attgct'

>>> dna.upper()

'ATTGCT'

>>> print(dna)

attgctThe contents of the variable 'dna' were returned in upper case. The contents of 'dna' were not altered.

count(str) returns the number of exact matches of str it found (as an int)

>>> dna = 'ATGCTGCATT'

>>> dna.count('T')

4The number of times 'T' is found is returned. The string stored in 'dna' is not altered.

replace(str1,str2) returns a new string with all matches of str1 in a string replaced with str2.

>>> dna = 'ATGCTGCATT'

>>> dna.replace('T','U')

'AUGCUGCAUU'

>>> print(dna)

ATGCTGCATT

>>> rna = dna.replace('T','U')

>>> print(rna)

AUGCUGCAUUAll occurrences of T are replaced by U. The new string is returned. The original string has not actually been altered. If you want to reuse the new string, store it in a variable.

Parts of a string can be located based on position and returned. This is because a string is a sequence. Coordinates start at 0. You add the coordinate in square brackets after the string's name.

This string 'ATTAAAGGGCCC' is made up of the following sequence of characters, and positions (starting at zero).

| Position/Index | Character |

|---|---|

| 0 | A |

| 1 | T |

| 2 | T |

| 3 | A |

| 4 | A |

| 5 | A |

| 6 | G |

| 7 | G |

| 8 | G |

| 9 | C |

| 10 | C |

| 11 | C |

Let's return the 4th, 5th, and 6th nucleotides. To do this, we need to count like a computer and start our string at 0 and return the 3rd, 4th, and 5th characters. This will be everything from 3 to 6. Python counts the gaps before each character in the string, starting at 0.

>>> dna = 'ATTAAAGGGCCC'

>>> sub_dna = dna[3:6]

>>> print(sub_dna)

AAAThe characters with indices 3, 4, 5 are returned. Or in other words, every character starting at index 3 and up to but not including, the index of 6 are returned.

Let's return the first 6 characters.

>>> dna = 'ATTAAAGGGCCC'

>>> sub_dna = dna[0:6]

>>> print(sub_dna)

ATTAAAEvery character starting at index 0 and up to but not including index 6 are returned. This is the same as dna[:6]

Let's return every character from index 6 to the end of the string.

>>> dna = 'ATTAAAGGGCCC'

>>> sub_dna = dna[6:]

>>> print(sub_dna)

GGGCCCWhen the second argument is left blank, every character from index 6 and greater is returned.

Let's return the last 3 characters.

>>> sub_dna = dna[-3:]

>>> print(sub_dna)

CCCWhen the second argument is left blank and the first argument is negative (-X), X characters from the end of the string are returned.

The positional index of an exact string in a larger string can be found and returned with the string method

find(). An exact string is given as an argument and the index of its first occurrence is returned. -1 is returned if it is not found.

>>> dna = 'ATTAAAGGGCCC'

>>> dna.find('T')

1

>>> dna.find('N')

-1The substring 'T' is found for the first time at index 1 in the string 'dna' so 1 is returned. The substring 'N' is not found, so -1 is returned.

Since these are methods, be sure to use in this format string.method().

| function | Description |

|---|---|

s.strip() |

returns a string with the whitespace removed from the start and end |

s.isalpha() |

tests if all the characters of the string are alphabetic characters. Returns True or False. |

s.isdigit() |

tests if all the characters of the string are numeric characters. Returns True or False. |

s.startswith('other_string') |

tests if the string starts with the string provided as an argument. Returns True or False. |

s.endswith('other_string') |

tests if the string ends with the string provided as an argument. Returns True or False. |

s.split('delim') |

splits the string on the given exact delimiter. Returns a list of substrings. If no argument is supplied, the string will be split on whitespace. |

s.join(list) |

opposite of split(). The elements of a list will be concatenated together using the string stored in 's' as a delimiter. |

Strings can be formated using the format() function. Pretty intuitive, but wait til you see the details! For example, if you want to include literal stings and variables in your print statement and do not want to concatenate or use multiple arguments in the print() function you can use string formatting.

>>> string = "This sequence: {} is {} nucleotides long and is found in {}."

>>> string.format(dna,dna_len,gene_name)

'This sequence: TGAACATCTAAAAGATGAAGTTT is 23 nucleotides long and is found in Brca1.'

>>> print(string) # string.format() does not alter string

This sequence: {} is {} nucleotides long and is found in {}.

>>> new_string = string.format(dna,dna_len,gene_name)

>>> print(new_string)

This sequence: TGAACATCTAAAAGATGAAGTTT is 23 nucleotides long and is found in Brca1.We put together the three variables and literal strings into a single string using the function format(). The original string is not altered, a new string is returned that incorporates the arguments. You can save the returned value in a new variable. Each {} is a placeholder for the strings that need to be inserted.

Something nice about format() is that you can print int and string variable types without converting first.

You can also directly call the format function on a string inside a print function. Here are two examples

>>> string = "This sequence: {} is {} nucleotides long and is found in {}."