32-bit floating-point package for the 65816

- IEEE-754 single precision

- Stack based with X register used as a floating-point stack pointer (FPSP)

- Floating-point values represented internally with a 32-bit mantissa (24-bit significand bits, including the hidden bit plus 8 guard bits for rounding)

- Functions

* fadd32, fsub32, fmult32, fdiv32 x+y, x-y, x*y, x/y

* fsquare32 x^2

* ftrunc32, uitrunc32 truncating functions

* floor32, fround32 rounding functions

* pushu32 convert unsigned int to float and push to fp stack

* str2fp32 convert ascii string to float and push to fp stack

* more to come as I have a need

This package is modified from Marco Granati's 128-bit floating-point package for the 65816. The original source file and my port of it to the ca65 assembler are in the scr folder. A discussion of the original code is available online.

128-bit floating-point is great to have for the 65816 if you need the precision but if you don't the extra precision consumes a lot of cycles that serve no purpose. Also, a fair number of cycles are needed to switch to the dedicated floating-point direct page and load arguments and retrieve results from the dedicated floating-point registers.

I wanted something faster, so I looked for ways to speed up the floating-point package. I noted a few possibilities when I added Marco's package to my system:

- Use the system direct page or avoid it altogether. The 128-bit fp package uses a dedicated direct page which must be shifted to and back for each fp operation (or this could be combined with the system direct page if you have enough space).

- Use a dedicated fp stack. The 128-bit fp package uses registers which must be loaded and the result retrieved from for each fp operation.

- Use 16-bit registers unless needed otherwise. The 128-bit fp package requires every fp operation to be called with 8-bit registers. Since my system uses 16-bit registers, this requires a switch before and after every fp operation.

I've greatly reduced this overhead by using a floating-point stack. I found the 32-bit package about 5.5 times faster than the 128-bit version running a Mandelbrot Set calculation. Converting to 32-bit acounted for most of this, about 4x, but the other overhead accounted for about 1.5x of it. I haven't done any optimization so perhaps this advantage could be increased.

Unlike Marco's original 128-bit fp package which uses a dedicated direct page and floating-point registers, this package utilizes a floating-point stack indexed with the X register. This loses some efficiency Marco gained by using faster address modes for some calculations, but it gains efficiency by not having to load and unload the registers for every operation. The functions work directly with the values on the floating-point stack and switching to the floating-point stack is as easy as loading the X register with the floating-point stack pointer.

To use, allocate a region of Bank 0 to serve as a floating-point stack. Maintain a pointer to this stack and load the X register with it prior to calling any of the floating-point functions. Save the pointer upon return from the function as it might have been changed by the operation. You might think the fp routines should switch to the stack but this is inefficient as it adds overhead to each fp call, whereas switching to the fp stack before the call allows several fp operations to be called in succession without the stack switching overhead.

The functions utilize the top two entries on the stack. Marcos' dedicated registers, the accumulator and argument, are equivalent to top of the stack value, TOS, and the next on stack value, NOS, respectively.

Each entry on the floating-point stack consists of 8 bytes. The first four bytes are the floating-point mantissa, with 24-bits devoted to the IEEE-754 single precision mantissa (including the hidden bit) and eight guard bits used for rounding (as well as making the algorithms easier to handle with 16-bit registers). These are stored little endian style, with the most significant byte highest in memory. The exponent comes next, with two bytes (only one used for 32-bit, but kept as a word for computational ease). A sign byte and status byte follow. Note that I might modify this structure as I consider how I want to handle the status byte. I've mostly followed Marco's usage so far, but may deviate from this as it adds overhead for features I'm not very interested in.

There are no dedicated floating-point registers as in Marco's package. Your routines need to interact with values on the floating-point stack. The stack fills downward. Functions that consume an operand will increase the stack pointer by 8 bytes. Functions that add an item to the stack will decrease the pointer by 8 bytes. You may want to create functions to work with the stack. See the Forth Standard for some function ideas. Below, I've provided a sample of FDUP, which duplicates the top item on the stack.

I use standard Forth stack notation in describing the functions, but you don't need a Forth system to use this package. For example, ( F: r1 r2 -- r3 ), represents the floating-point values on the stack before and after a function call. Here r1 and r2 are the values on the stack before the call and r3 is the value on the stack after the call. r2 is on the top of the stack, or TOS (lowest in memory) and r1 is next on stack, or NOS (8 bytes higher in memory). r3 is the result of the function and is on the top of the stack after the call. This means the function has deleted a value on the stack by incrementing the floating-point stack pointer in the X register. You should save the stack pointer upon return from a fp call and restore it to the X register prior to the next fp call. The TOS and NOS values can be considered pseudo registers as they are used in the various floating-point functions. The structure of these pseudo registers is:

; TOSm: .res 4 ; mantissa (24 bits including hidden 1) + guard bits (8 bits)

; TOSe: .word 0 ; biased exponent

; TOSsgn: .byte 0 ; mantissa sign

; TOSst: .byte 0 ; status of floating-point value

You can use constants to ease access to the fp stack, such as:

; 32-bit floating-point stack offsets

TOSm = 0

TOSe = 4

TOSsgn = 6

TOSst = 7

NOSm = TOSm + FP_size

NOSe = TOSe + FP_size

NOSsgn = TOSsgn + FP_size

NOSst = TOSst + FP_size

I've consolidated the variables used in the package to some extent in order to reduce its footprint. No direct page usage is required, but you'll have better performance by locating a group of variables to the direct page (18 bytes total). A remaining 10 bytes are used during string to floating-point conversion and can be located in the current data bank. See the variables section for more information.

The package would be pretty useless without a way to get values on the floating-point stack. The functions pushu32 and str2fp32 help with this. Use pushu32 to convert an unsigned integer to a float and push it to the floating-point stack. Use str2fp32 to convert an ascii string to a float and push it to the stack.

The pushu32 function is a version of Marco's fldu32 function. Call it with an unsigned 32-bit integer in the A and Y registers (Y-lsw, A=msw). As the name implies, it will push the 32-bit floating-point equivalent to the stack.

The str2fp32 function is a streamlined version of Marco's str2fp function, but only handles decimal values. The code still has some of Marco's error checking, but I'll likely remove that as it's not needed in Forth (if the value isn't a proper fp value the system will try to interpret it as something else). The string is parsed from left to right. The expected format is a decimal ascii string, beginning with an optional '+' or '-' sign, followed by a decimal mantissa consisting of a sequence of decimal digits optionally containing a decimal-point character, '.'. The mantissa may be optionally followed by an exponent. An exponent consists of an 'E' or 'e' followed by an optional plus or minus sign, followed by a sequence of decimal digits. The exponent indicates the power of 10 by which the mantissa should be scaled.

Call str2fp32 with the address of a string in current data bank in the Accumulator and the length of the string in the Y register. This is a change from Marco's code, which uses a null terminated string or invalid character to end conversion. My interpreter provides the string length for free so this is easy for me. You can revert the code if it isn't for you.

You're on you own. Marco has a function, fp2str, to convert the value in the floating-point accumulator to a string that was too much of a pain to convert to 32-bit. Besides, my Forth operating system already has routines to handle number to string conversions and it was easier to use those. Unfortunately, these are not useable outside a 65816 Forth operating system, so wouldn't be useful to most people.

Note that with the exception of the exponent which uses a different bias, the internal representation of a floating-point value in the 32-bit package is just a truncated version of the 128-bit package. The bit patterns line up just right for that, unlike a 64-bit value. As such you could use Marco's fp2str function by transfering the 32-bit stack item to the 128-bit floating-point accumulator, converting the exponent to 128-bit precision as appropriate. The main downside of this is that you need to maintain at least a portion of Marco's package and since the function isn't standalone, extracting it is easier said than done. If you have the memory it's probably easier to include both packages. I've generally renamed global functions to eliminate duplicate symbols if both packages are included.

Conversion to IEEE-754 single precision binary interchange format is easy though. I give an example below.

- fadd32 ( F: r1 r2 -- r3 ) - Add r1 to r2 giving the sum r3

- fsub32 ( F: r1 r2 -- r3 ) - Subtract r2 from r1, giving r3

- fmult32 ( F: r1 r2 -- r3 ) - Multiply r1 by r2 giving r3

- fdiv32 ( F: r1 r2 -- r3 ) - Divide r1 by r2, giving the quotient r3

- fsquare32 ( F: r1 -- r2 ) - r2 is the square of r1

- ftrunc32 ( F: r1 -- r2 ) - Rounds r1 to an integral value using the "round towards zero" rule, giving r2

- uitrunc32 ( F: r -- ) - Return the integral part of r as an unsigned 32 bit integer in A=msw and Y=lsw

- floor32 ( F: r1 -- r2 ) - Round r1 to an integral value using the "round toward negative infinity"

- fround32 ( F: r1 -- r2 ) - Round r1 to an integral value using the "round to nearest" rule, giving r2

- pushu32 ( F: -- r1 ) - push r1 onto stack. r1 is the floating-point equivalent of the unsigned 32-bit integer, n, in the A and Y regsters (Y-lsw, A=msw) when called.

- str2fp32 ( F: -- r ) - Convert the source string to float r and place it on the TOS. Call with A = address of string in current data bank and Y is string length.

- Sample function call:

; F+ ( F: r1 r2 -- r3 )

; Add r1 to r2 giving the sum r3

; https://forth-standard.org/standard/float/FPlus

xt_fplus:

phx ; save data stack pointer

ldx FPSP ; switch to fp stack

jsr fadd32 ; add r1 and r2

stx FPSP ; save fp stack pointer

plx ; retrieve data stack pointer

z_fplus:

rtl

- Sample fp stack manipulation, duplicate top item on the fp stack:

; FDUP ( F: r -- r r )

; Duplicate r

; https://forth-standard.org/standard/float/FDUP

xt_fdup:

phx

phb

lda FPSP

tay

dey

clc

adc #FP_size-1

tax

lda #FP_size-1

mvp #0,#0

iny

sty FPSP

plb

plx

z_fdup:

rtl

- Convert the top item on the fp stack to a IEEE-754 hex value:

; >IEEE32 ( -- d ) ( F: r1 -- r1 )

; d is the IEEE-754 32-bit representation of r1

;

; byte offset

; 0 0 2 3 4 5 6 7

; 99 99 99 99 7F 00 40 00

; xx mm mm mm ee s

; <W1 > < W2 >

xt_toieee32:

phx ; save data stack pointer

ldx FPSP ; set fp stack frame

lda TOSm+1,x

sta W1 ; set low word of ieee-754 32-bit

acc8

lda TOSm+3,x ; mantissa msb

asl ; drop hidden bit

sta W2

lda TOSe,x ; exponent

lsr ; shift out lsb

ror W2 ; into ieee

sta W2+1 ; store rest of shifted exponent

lda TOSsgn,x

bpl @1

lda #$80 ; set sign bit

tsb W2+1

@1:

lda TOSm,x

cmp #$80 ; is guard byte >= $80

acc16

bcc @2

inc W1 ; round up low word

bne @2

lda #0

adc W2

sta W2

@2:

plx ; restore data stack pointer

dex ; make room on stack

dex

dex

dex

lda W1 ; save 32-bit ieee-754 value as d

sta NOS,x

lda W2

sta TOS,x

z_toieee32:

rtl

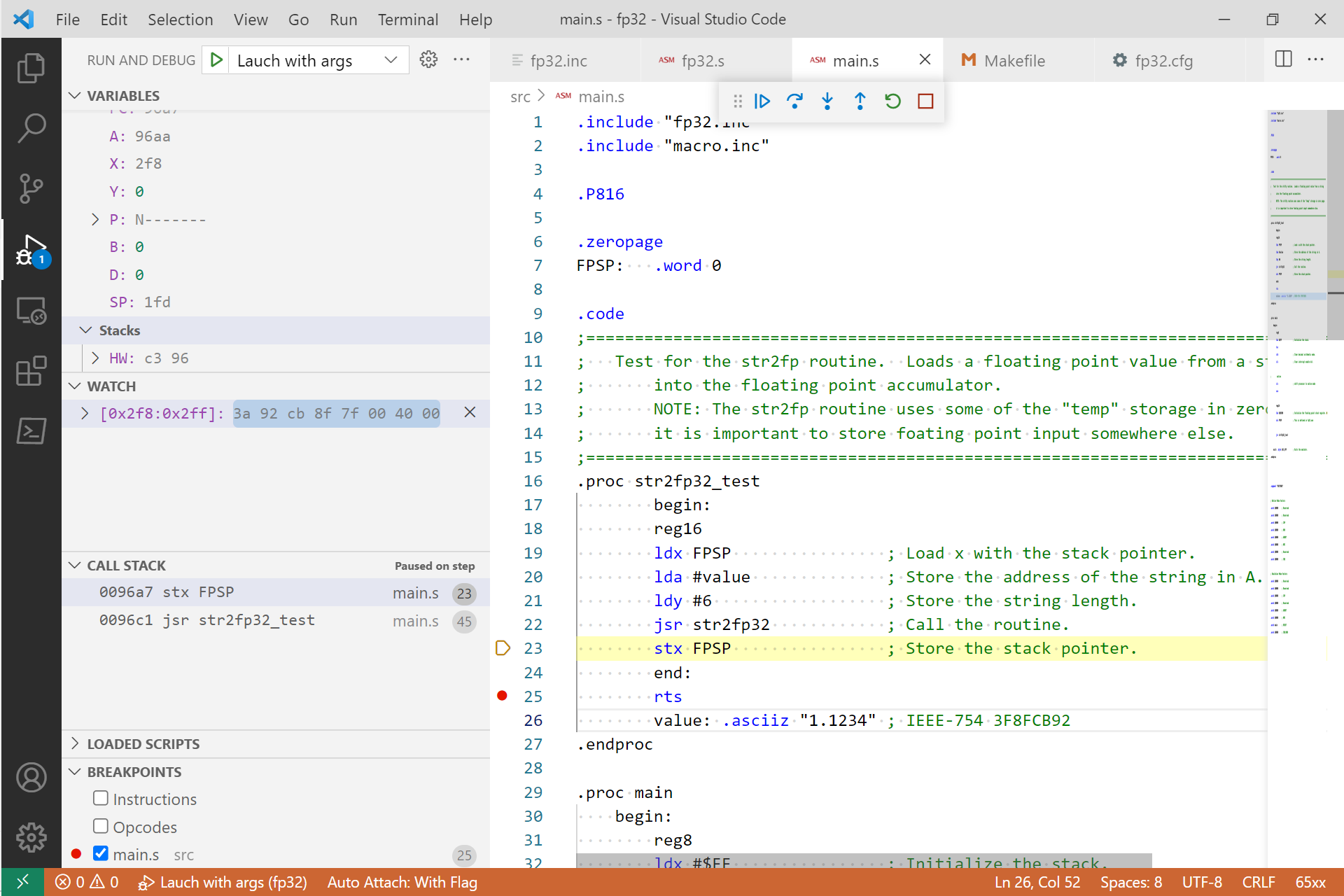

A reader of my blog sent me a simple test program for the 32-bit floating-point package. It just adds a value to the floating-point stack. I modified it slightly for it to work with with my VS Code 65816 debugging extension. You can read more about it and download source code that you can modify for your own use at my blog post 65816: Testing the 32-bit Floating Point Package with the VS Code db65xx Debugging Extension.

I've done limited testing of both Marco's original 128-bit package as well as my own 32-bit version. I wrote about testing the packages with a Mandelbrot plot in my blog. I've also tested the 32-bit package functions with the tests found in the tests folder. These are Forth based and not exhaustive. Use the package as your own risk.

- The 32-bit package has a very limited subset of Marco's fp functions. I'll likely add more, but most likely only when I need them for my projects. However, once you understand floating-point, it's not hard modifying Marco's code to add your own 32-bit versions of them.

- I've focused this development on my system. I'm not interested in infinities and NANs and haven't tested any of the functions with such values. Some of Marco's original code handling these is still in the package but I'll likely remove it as it adds overhead that I'd rather avoid.

- Some of Marco's error checking remains and may or may not still be functional. I haven't tested the package with problematic fp values. Some more error checking is probably needed in some places, but isn't a focus right now (and might never be). Again, use at your own risk.

- I still have a lot of cleanup to do on the file.

- As mentioned, using a floating-point stack reduces the flexibility to use some address modes to increase performance. Still there are likely improvements that can be made to my code. In some places I've replace algorithms used by Marco with my own to facilitate package creation rather than translating Marco's more complex, and likely faster code.