General matrix/matrix multiplication (GEMM) is a core routine of many popular algorithms. On modern computing platforms with hierarchical memory architecture, it is typically possible that we can reach near-optimal performance for GEMM. For example, on most x86 CPUs, Intel MKL, as well as other well-known BLAS implementations including OpenBLAS and BLIS, can provide >90% of the peak performance for GEMM. On the GPU side, cuBLAS, provided by NVIDIA, can also provide near-optimal performance for GEMM. Though optimizing serial implementation of GEMM on x86 platforms is never a new topic, a tutorial discussing optimizing GEMM on x86 platforms with AVX512 instructions is missing among existing learning resources online. Additionally, with the increasing on data width compared between AVX512 and its predecessors AVX2, AVX, SSE4 and etc, the gap between the peak computational capability and the memory bandwidth continues growing. This simultaneously gives rise of the requirement on programmers to design more delicate prefetching schemes in order to hide the memory latency. Comparing with existed turials, ours is the first one which not only touches the implementation leaveraging AVX512 instructions, and provides step-wise optimization with prefetching strategies as well. The DGEMM implementation eventually reaches comparable performance to Intel MKL.

I warmly welcome questions and discussions through pull requests or my personal email at yujiazhai94@gmail.com

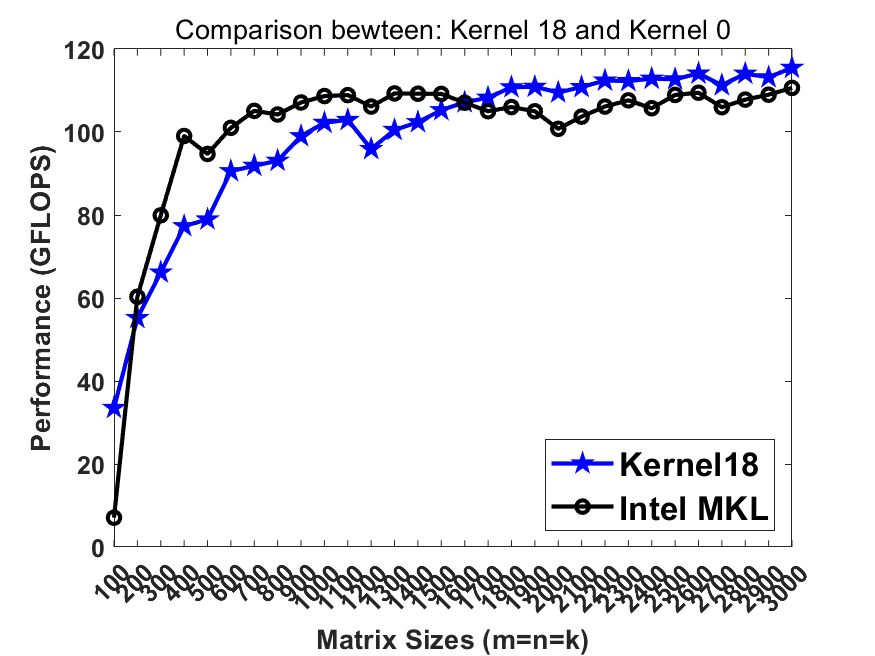

- We require a CPU with the CPU flag

avx512fto run all test cases in this tutorial. This can be checked on terminal using the command:lscpu | grep "avx512f". - The experimental data shown are collected on an Intel Xeon W-2255 CPU (2 AVX512 units, base frequency 3.7 GHz, turbo boost frequency running AVX512 instructions on a single core: 4.0 GHz). This workstation is equipped with 4X8GB=32GB DRAM at 2933 GHz. The theoretical peak performance on a single core is: 2(FMA)*2(AVX512 Units)*512(data with)/64(bit of a fp64 number)*4 GHz = 128 GFLOPS.

- We compiled the program with

gcc 7.3.0under Ubuntu 18.04.5 LTS. - Intel MKL version: oneMKL 2021.1 beta.

Just three steps.

- We first modify the path of MKL in

Makefile. - Second, type in

maketo compile. A binary executabledgemm_x86will be generated. - Third, run the binary using

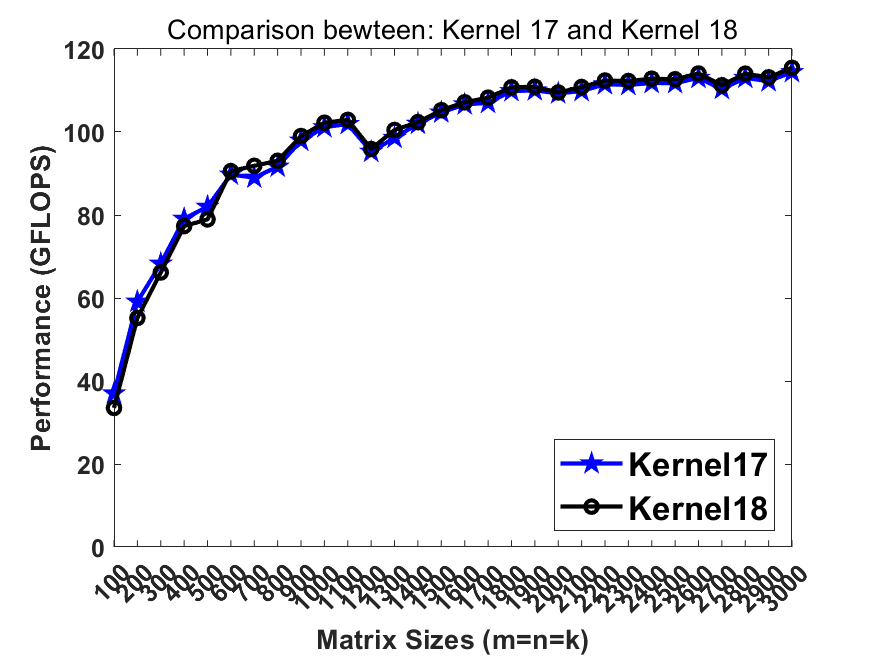

./dgemm_x86 [kernel_number], wherekernel_numberselects the kernel for benchmark.0represents Intel MKL and1-19represent 19 kernels demonstrating the optimizing strategies. Herekernel18is the best serial version whilekernel19is the best parallel version. Both of them reach the performance comparable to / faster than Intel MKL on lastest Intel CPUs.

- https://github.com/flame/how-to-optimize-gemm

- http://apfel.mathematik.uni-ulm.de/~lehn/sghpc/gemm/index.html

- https://github.com/wjc404/GEMM_AVX512F

- https://github.com/xianyi/OpenBLAS/tree/develop/kernel/x86_64

Here we take the column-major implemetation for DGEMM.

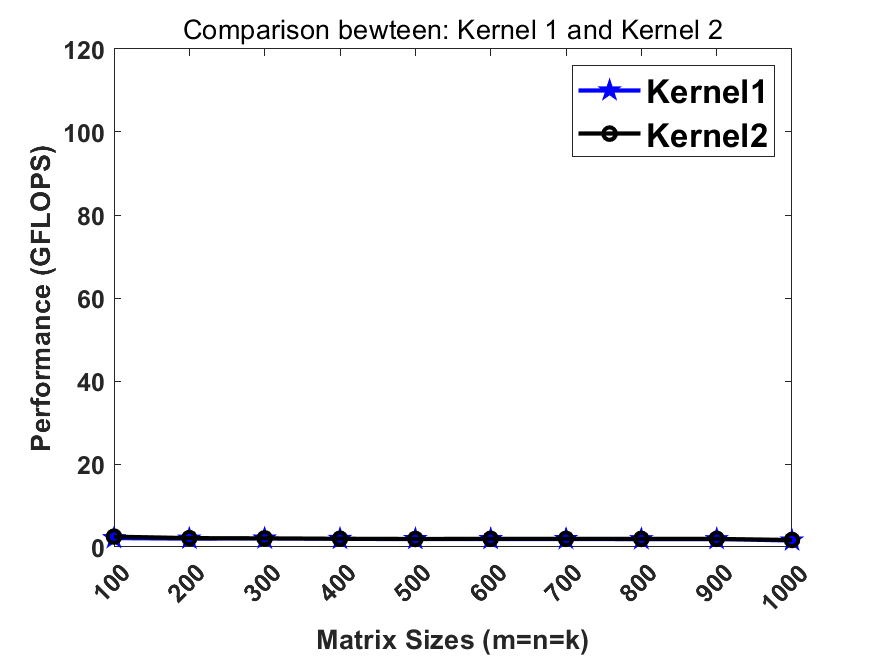

Kernel 1 is the most naive implementation of DGEMM.

Observing the innermost loop in kernel1, C(i,j) is irrelevant to the innermost loop index k, therefore, one can load it into the register before entering the k-loop to avoid unnecessary memory access.

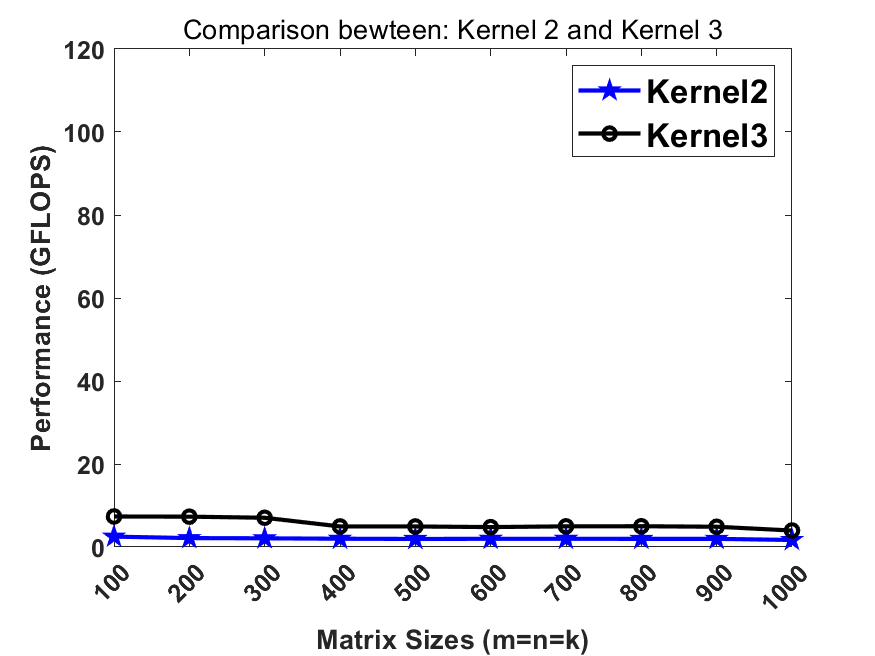

Since matrix multiplication is an algorithm at the complexity order of N^3, one should basically re-use the data at register/cache levels to improve the performance. In kernel2, we cached a C element in register but failed to re-use the data on matrix A and B at the register level. Now we update the whole 2x2 block of C matrix by loading a 2x1 slice of A and an 1x2 slice of B. Then we conduct an outer-product rank-1 update on the 2x2 C block. This significantly improves the performance compared to the previous step.

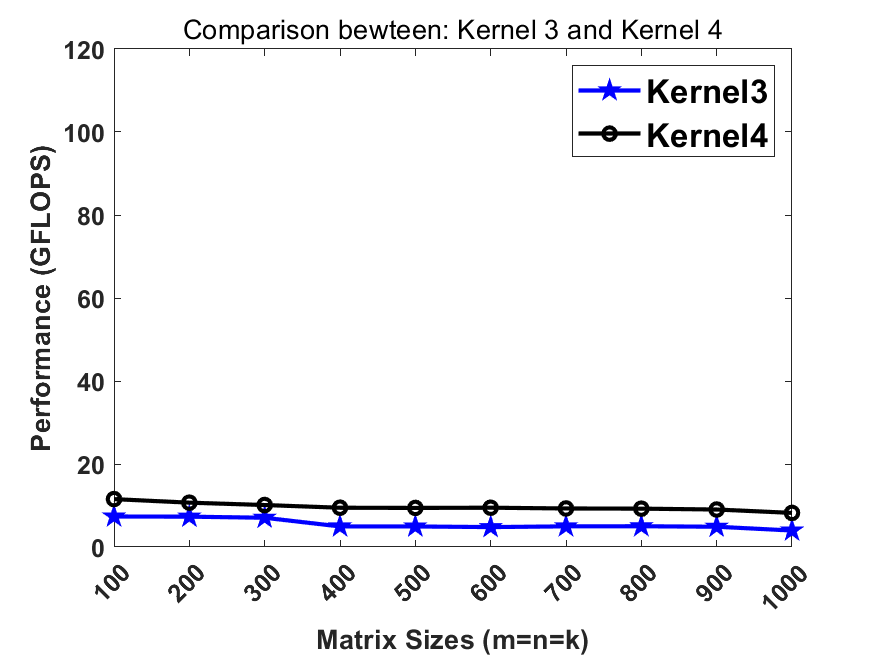

Now we more aggresively leverage the register-blocking strategy. We update on an 4x4 C block each time. The performance further improves.

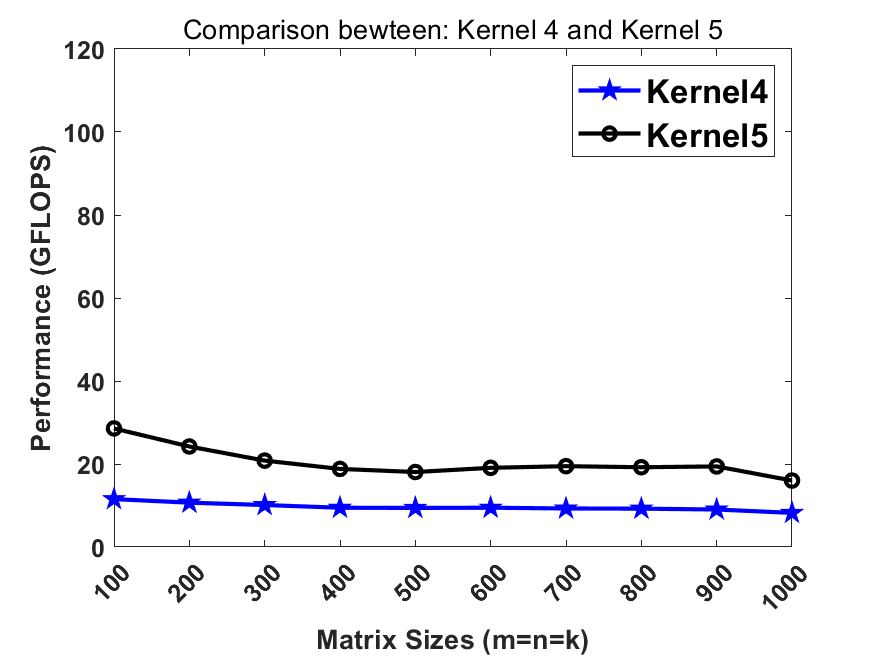

Instead of processing data with scalar instructions, now we process data using Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions. An AVX2 instruction, whose data width is 256-bit, can process 4 fp64 elements at a lane.

We unroll the loop by 4 folds. This step slightly improves the performance.

We changed the previous kernel from 4x4 to the current 8x4 so that we obtain a better utilization on all 256-bit YMM registers (16 YMMs on SNB/HSW/BRW and 32 YMM/ZMM on SKL/CSL).

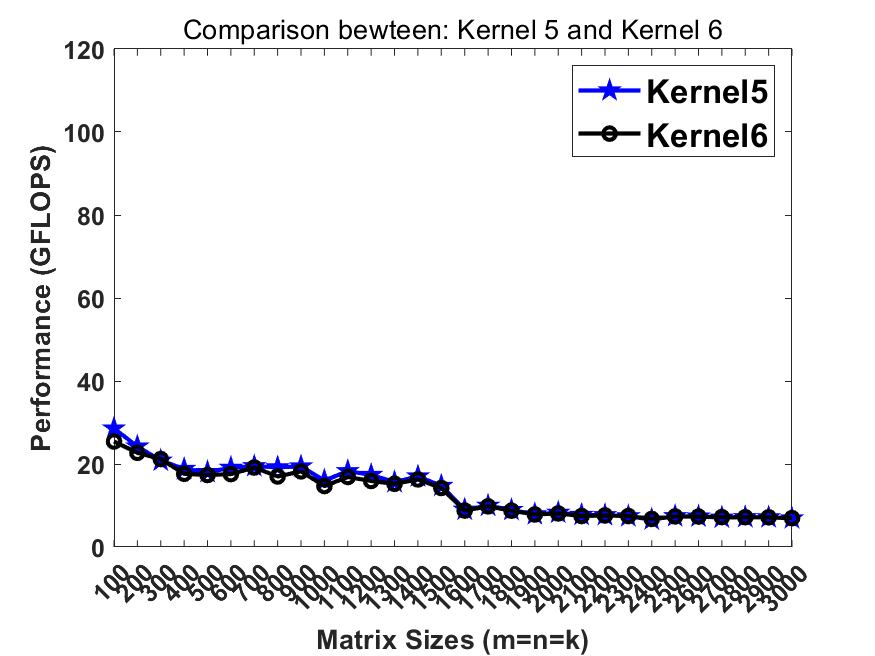

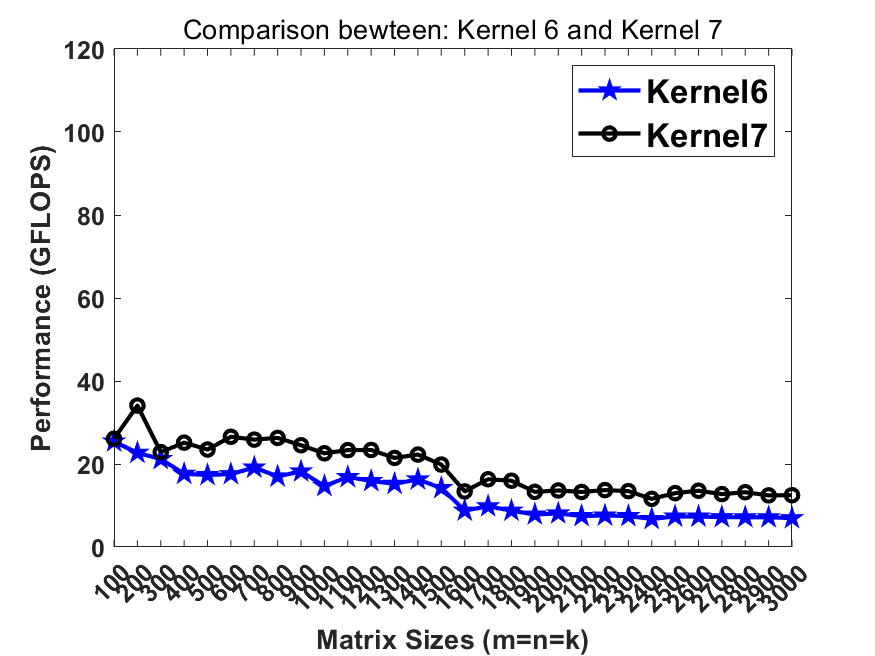

We notice that the performance around 30 GFLOPS cannot be maintained when data cannot be held in cache. Therefore, we introduce cache blocking to maintain the good performance when matrix sizes are small.

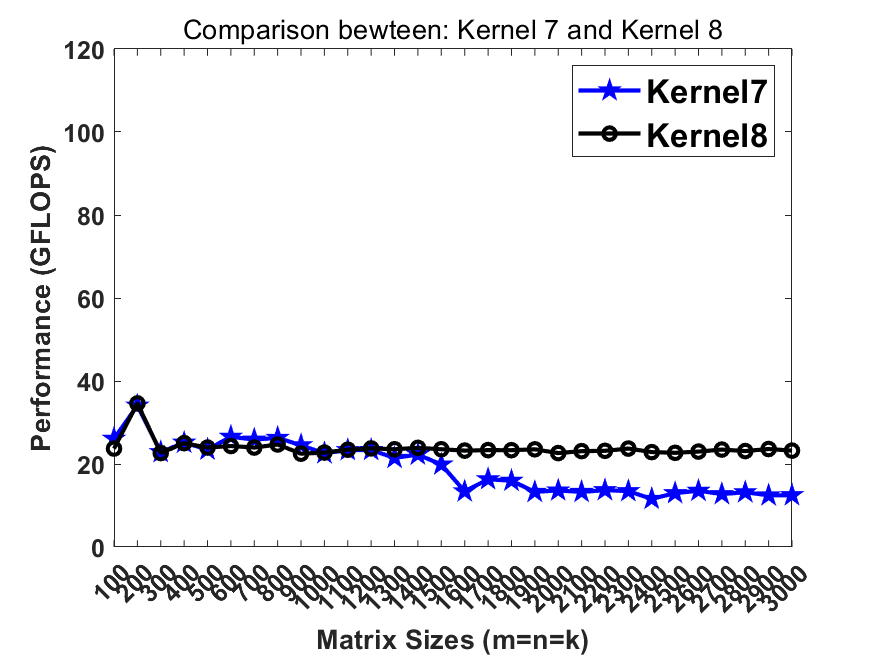

To avoid the TLB miss when accessing the cache blocks, we pack the data blocks into continous memory before loading them. This strategy boosts the performance.

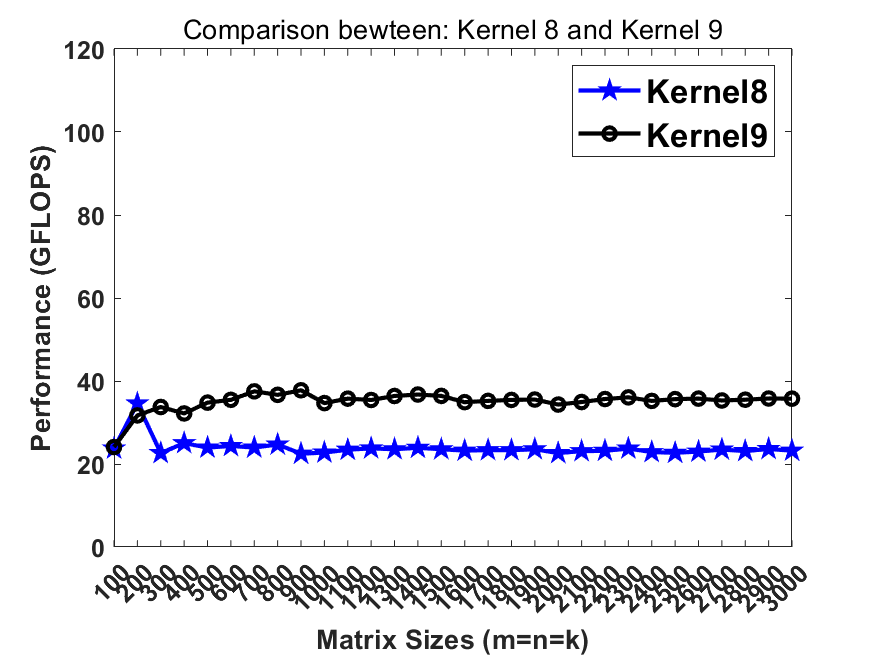

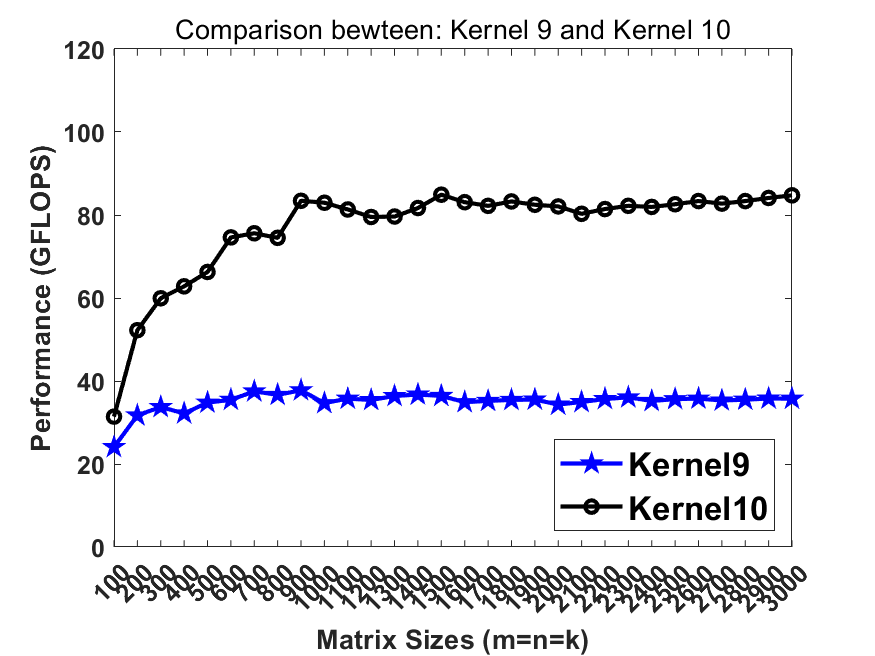

We update kernel9 with a larger micro kernel (24x8 instead of 8x4) and wider data width (AVX512 instead of AVX2). All other strategies maintain.

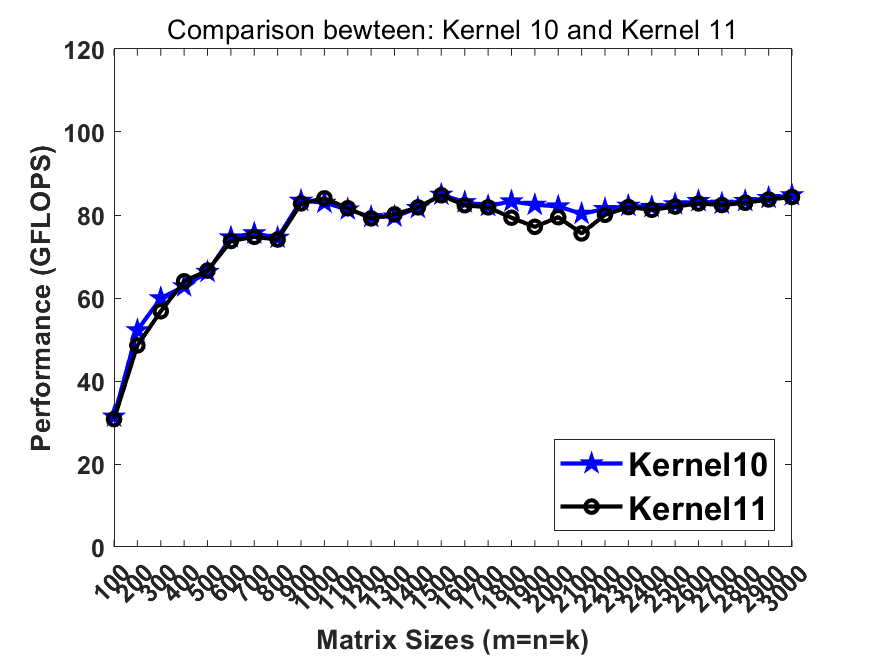

Previously in kernel10 we pack the matrix B into totally continous memory. Recalling that the L2 cache contains multiple cache line buffers so that the L2 hardware prefetcher can prefetch the data from lower memory hierarchy. In this step, breaking the continous memory access in B can benefit the L2 hw prefetcher so that the memory latency can be further hidden.